McCarthy, Cruz, and Chavez

There’s still no full analysis of the economic impact of the federal government’s shutdown in New Mexico, but I bet Ted Cruz and the Tea Party would have a tough time getting a smile in Carlsbad these days. The shutdown made an unsightly dent in the revenue of cafés, motels, bars, tourist shops and gas stations that depend on the 400,000 annual visitors to Carlsbad Caverns National Park.

Still suffering an unemployment (and underemployment) crisis from the 2008 Great Recession, New Mexico, the poorest state in the union, got another kick in the head when some 27,000 federal employees, and their buying power, were put into political cold storage for 16 days. The 27,000 missing paychecks, no matter if only “temporarily gone,” hacked their way though our economy like a kind of virus, diminishing the well-being of everyone from plumbers and gardeners, to bookstores and clothiers, to mechanics and grocers, and dentists and carpenters, to everyone else who depended directly or indirectly on those missing paychecks.

No wonder folks are mad at the Tea Baggers and their Dracula-like leader, the very junior Senator from Texas Ted Cruz, who seems to take religious pleasure out of trying to squeeze blood from stones.

Every time I watch Ted Cruz speak, building his rhetorical economic horror shows designed to stoke anxiety and vanquish hope, I think of Senator Joe McCarthy, who scared the country into a ruthless, witch-hunting madness with his attacks on supposed communist infiltrators whom he lumped together with “homosexuals,” playing on the nation’s worst instincts and deepest prejudices, much like the Nazis, and others of their kind, always have.

Now Ted Cruz is no Joe McCarthy, at least not yet. But he does thrive on fear like all demagogues do. He fuels the passions of his supporters with the energy of a message that spreads economic terror about sinister, amorphous threats like the national debt and “socialized” medicine, both supposed devils he conjures up like a sideshow magician. He is driven, like McCarthy, by an obsessive single-mindedness. A religious, hell-fire fanaticism runs like lava through his politics, much like McCarthy’s manipulative religiosity singed his victims. Cruz tells us that he’s heard God, himself, proclaim His support for Ted’s economic views.

When it comes to the Affordable Care Act, Senator Cruz, and his economist deity, is happy to put the whole nation at risk, as food inspectors and cancer researchers, along with a host of other medical support staff, are stopped from caring for vulnerable children, women and old people, just for the sake of something as ephemeral as an economic theory, approved by God or not.

The shutdown could well have compromised the health of thousands, condemning many of them to premature and painful death without due process of human law, but rather with the fantastical pronouncements of a politician with God whispering in his ear. As he says of his compulsions, “God’s will be done.” Or is it really “Ted’s will be done.”

Where are the senators today who can stand up to their colleague and say of Cruz what the late U.S. Senator Dennis Chavez of New Mexico said about Joe McCarthy and his influence, pleading with his peers to return to “decency, sanity, and the basic principles of due process.”

Chavez, one of the earliest opponents of McCarthyism, rose to the Senate floor in l950 and said, “I should like to be remembered as the man who raised a voice and I devoutly hope not a voice in the wilderness at a time in the history of this body when we seem bent upon placing limitations on the freedom of the individual. I would consider all of the legislation which I have supported meaningless if I were to sit idly by, silent, during a period which may go down in history as an era when we permitted the curtailment of our liberties, a period when we quietly shackled the growth of men’s minds.”

That’s what fear does. It shackles the mind. It turns individuals into members of a mob, it limits individual freedom by manipulating how a person thinks, often replacing thought with hate. When hate and fear are combined, liberty finds itself bound and gagged and tossed into a deep pit, awaiting heroic rescue, and heroes like Dennis Chavez.

When a politician and a political movement, like Ted Cruz and the Tea Party, whip people up into hating their own government and the whole notion of government in general, equating religious and economic anarchy with so-called American values, they preach a kind of neo-McCarthyism in which government itself, and all the vital services it provides to all of us, and which we pay for as taxpayers, is seen as subversive and immoral. If you hate our government on principle, you hate our Constitution on principle too. And when you do that, you hate the people our government represents. This is McCarthyism growing into the doctrine of a would-be tyrant who hears voices he thinks come from God.

Muertos y Marigold Parade

Almost 108 billion human beings have been born on this planet in the last 50,000 years since primates became fully developed humans with language, music, and cultural diversity and richness. And some 100 billion of them are dead.

Included in this celestial horde are those people whom we have loved, who have loved us, and who have helped make us into the people we have become. For most older people, their parents are long gone. And the list of lost friends and relatives and mentors and soul mates is so long we can hardly imagine the toll of the years. We can be overwhelmed, sometimes, by the sinking hollow magnitude of the loss of such people, of their vanishing from the palpable world. And as much as our memories of them can comfort us, it’s never quite enough to compensate for that sense of being somehow stranded in this life without them.

Our Milky Way has some 300 billion stars. Imagine that slightly more than a third of those stars represents the human dead, a glowing effulgence of lost lives, all of them important to someone at sometime. Our personal losses are mirrored by the grief of innumerable other people suffering the absence of those they cared for. Each one of those 100 billion no longer here were so like us – with their fears, their humor, their bad habits, their generosity, their exhaustion, their moments of insight and courage – that it could be said that all of them are a part of our extended family, as indeed they are in death, even if history, culture, and geography never let them be in life. Some of them were abominable, some were the saviors of their people. The rest were of such variety, such idiosyncrasy, that they could never be characterized.

Each and every one of them, though, have one thing we do not and cannot have until we join them – the experience of what it means to be not alive. That is for us a mystery as distant as the stars. That’s why Dia de los Muertos is celebrated, to bring those “stars” closer to us, to renew their lives with the love we feel for them, and to remind ourselves of what we all know but the poet Virgil said so clearly : “Death plucks my ear and says, ‘Live, I am coming.’”

Learning to live with death and with the dead is the greatest tonic for not having the dread of it ruin your life. That’s why, for me, Dia de los Muertos and the Marigold Parade celebrations in Albuquerque’s South Valley are such a life affirming gift to us all. They help us accept what Is – that the living must make room for new life by leaving the stage.

I remember my first Dia de los Muertos in l960 in the town of Cholula, Mexico, near Puebla, south of Mexico City. I was 20 and had heard of the town as having 365 churches in it to counteract the mountainous ancient temple there. The basilica of Nuestra Senora de los Remedios was built on top of it. I’d never heard of a Dia de los Muertos before. So when I stumbled onto it that November 2, I was literally transported from that sort of gloom that is so pervasive we hardly know it’s there until we experience the relief of it being gone. I’d lost two dear teachers and life guides a few years before, so when all the candles, marigolds, masks, candy and sugar skulls confronted me in such an enormous profusion of merriment and solemnity, I realized that my loss allowed me to be a part of this enormous community whose members were at once mourning their losses and celebrating not only their lives, and the lives of the living whom they love, but also reveling in the realization that they were, against many odds, still alive themselves.

My old teachers that day came back to me. Rosalie Buddington, who produced Christmas plays of her own authorship every year and in one of which I starred as a Christmas pixie when I was ten and learned how not to be afraid; and Clifford Brook, Brooky as he was called, whose monocle exploded from his eye every time he read me Captain Marvel comic books and pronounced the word SHAZAM! The joy they took in being alive came back to life in me that afternoon and evening in Cholula.

When the Dia de los Muertos y Marigold Parade starts up November 3 this year on Isleta Boulevard in the South Valley, people in marigold covered floats, skull masks and skeleton getup, people dancing and jumping and singing and rattling and making joyous noises, hundreds if not thousands of people will celebrate the lives of the dead and the lives of the living,

When you think of a 100 billion of us already dead, you sense how rare it is, in the vast scheme of evolution, to be alive at all. But as the great song writers Gus Kahn and Raymond Eagan observed “In the meantime, In between time, Ain’t we got fun.”

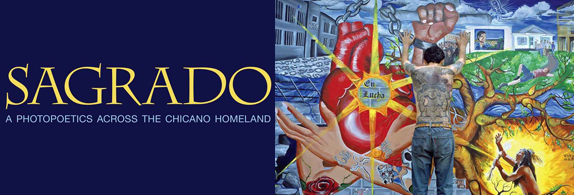

Sagrado: A Photopoetics Across the Chicano Homeland

The love of home is perhaps the most universal and personal of human emotions. This one feeling connects us with most other human beings. It’s the grounding of empathy. Because each of us knows what this feeling is like in the deepest part of our interior secret lives, it becomes both something supremely intimate we share with almost everyone, and something so personal and culturally specific we find it hard to express.

Sagrado: A Photopoetics Across the Chicano Homeland, published recently by UNM Press, is a universal book grounded in a universal emotion that is one of the most beautiful and inspiring evocations I’ve experienced of the vast Chicano community congregated throughout the Southwest, especially in New Mexico, a community and homeland woven together by more than 500 years of history.

With poems by New Mexico Centennial Poetry Laureate Levi Romero, photographs by Robert Kaiser of Las Cruces, and a narrative by New Mexico State Spanish professor Spencer R. Herrera, the synergistic gravity of Sagrado pulls readers in no matter their background or frame of reference.

Sagrado is part of UNM Press’s Querencias Series, edited by Miguel Gandert and Enrique Lamadrid. Querencia refers to “a popular term in the Spanish-speaking world used to express love of place and love of people.” The series, the Press says, “promotes a translational, humanistic, and creative vision of the U.S.-Mexican borderlands based on all aspects of expressive culture, both material and intangible.” That aptly describes the intensity of focus that gives Sagrado its universal openness.

Kaiser’s color photographs were shot all over the Chicano West, from Las Cruces, Tucson, and Anthony, New Mexico to Canutillo, Texas, Vado, New Mexico and Juarez. Images of vaqueros and boot makers, low riders and boxers, wonderful old trucks, people serenading each other with guitars, little plazas, composantos, and “badass vatos,” flamenco artists and rodeo riders, ceremonial dancers, devout pilgrims, the iron bars between Mexico and the US, and field hands picking chile. The photographs have a feeling of immediacy and intimacy that allows you to see them as the work of a gifted and sympathetic witness, an artist who gets out of the way so you can see what he sees without the sense of an intermediary directing your emotions and responses. Unlike many photography books, the images are not presented in a museum-portfolio format. They move though the texts, and the texts move through them in a way that is thoroughly absorbing.

Reading Herrera’s narrative and Romero’s poems in the context of Kaiser’s photographs makes Sagrado an event of learning and feeling that transcends the sum of its parts. And its parts are wonderful in and of themselves.

Herrera’s narrative describes the process of his self-revelation, a reinvention of himself from a monolingual English speaker into the scholar, linguist, and teacher who could write the beautifully personal story in this book, a story that somehow is not only is a description of his struggles for identity but also a celebration of what it means to become culturally self-actualized.

In the Prologue, Herrera writes of the Mexican-Americans “beginning to carve out a space as part of the American social fabric.” He continues:

To triage the cultural hemorrhaging (suffered after the U.S. war of 1848 with Mexico) required an introspective look into who we were and where we came from. With the onset of the Chicano movement of the l960s, we began to explore these two questions and many more. One of the major cultural developments born out of the Chicano movement was the resurgence of the notion of Aztlan the mythical homeland of the Aztecs and the cultural origin of Chicano identity. Many scholars believe that Aztlan lies in the Southwestern United States. For this reason, Chicanos have come to embrace the idea that the Southwest is our ancestral homeland. Ironically, it is the place we lost and yet currently occupy.

Levi Romero’s poems in Sagrado can have a liturgical grace. He speaks at times in a voice that is solemn but without self-importance. Reading him is always filled with the joy of open-heartedness, the generosity of appreciation and wondering attention to detail. His poem “Years after my father died,” runs down the right side of two pages that a Kaiser photograph of a weathered door, set into a weathered whitewashed wall, with the whitewash itself all but washed away. The poem continues from the title:

and his body was lain into the earth

his garden continued to yield vegetables

radishes and carrots burred into the dark

moist dirt and the onion stalks stood straight

as the soldiers standing for the twenty-one gun salute

yesterday morning crickets purred

under the shade of the last broad

green leafed plant in the yard

while insects flicked under a canopy

of morning glories

the last time I saw you

we spoke of conflict

and that all endings

must have resolution

this afternoon I long

for the voice of the

red breasted robin

I yearn for the slow sinking rhythm

of a long summer evening

and warm conversation

a thin thread of web glistens

in the crook of the plum tree

I am accompanied only

by the caw and the swooping flight

of the crow across the afternoon sky

the sunflowers in the meadow

are crowned with halos of petals

browned and golden in the haze

of autumn sunlight

crouched and looking

like old men

with wrinkled faces

their reach toward the sun

frozen in a final grasp

toward warmth and light

Sagrado is one of those books I’d like to give to everyone I know. It speaks of the human world as it is and, I think, as it should be – a world full of love and pride and honor and deep commitment to other people in the face of the forces of history and chance that come upon us without warning and stay with us without pity, forces we are required to overcome by our inner strength as individuals, and by our inner bonding with our community and as members of the family of humankind.

(Dia de los Muertos photos: Girl by Larry Lamsa; puppet by City of ABQ; boy by Ingrid Truemper)

Responses to “Provincial Matters, 10-28-2013”