Resilience: Adapting to Drought in the Southwest

The history of climate adaptation in New Mexico and the arid Southwest, particularly when it comes to water and drought, is like an unopened textbook. People have been surviving horrendous droughts and normally dry and difficult conditions here for millennia. Not only did they understand how to sustain themselves and survive, they knew how to be resilient when it came to growing food.

Resilience and sustainability have been matters of interest for a minority of architects and planners around the world for the last twenty years or so. But as the consequences of climate change are becoming more and more apparent, the focus on this fundamental shift in temperature and weather volatility becomes more attentive and direct.

The American Institute of Architects (AIA) is sponsoring classes and conferences around the country that promote discussions on how to cope productively with climate change and related natural disasters. The AIA is also working to change confusing terminology, replacing “sustainability” with the “resilience.” “Sustainability” connotes preserving, or sustaining the status quo, not adapting to evolving new conditions.

At the AIA national convention last year, New Mexico’s Ed Mazria, “one of the pioneers of the of the sustainable design movement,” asked in a keynote address “Why design with a purpose? It’s because life depends on it.”

Mazria continued “Every major scientific organization is telling us that we have a choice—to stay under two degrees centigrade global warming and then bring the planet back to pre-industrial levels, which is the climate we have always known or go on with business as usual” which would amount to a colossal human-made natural disaster.

Achieving “carbon neutrality” has a life-saving purpose and one that poses enormous creative challenges and chances for innovation. Mazria’s big effort is called Architecture 2030 in which he says that 75 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions come from cities. Some 60 percent of the “entire building stock of the world” will be replaced and rebuilt in the normal course of events before 2030. If resilient building practices are adopted on a scale such as this, carbon emissions could be so drastically reduced that carbon neutrality might be in reach again.

Massive changes in regional, or even global, environments must be adapted to on the local level to meet the unique demands of countless different microclimates. Over much of the Southwest lately, climate change seems to be delivering water in different ways and with different frequencies than in the past. Heavy winter snowpacks, which most water infrastructure is designed to channel and store, seem to be on the decline. They are increasingly being replaced by unpredictable monsoonal flooding in the summer which most cities aren’t equipped to handle in a way that both protects property and maximizes flood water storage and distribution.

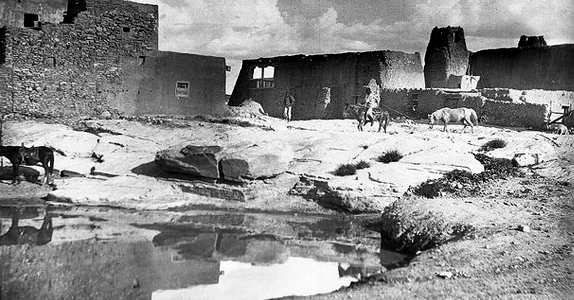

The textbook for adapting to Southwest water variations has been written, so to speak, by the Pueblo cultures of New Mexico and Arizona. They have endured as agricultural communities, with their evolving cultures, since or even before corn arrived from Mesoamerica around 2100 BC. Their mastery of resilience in design and agriculture is not a matter of speculation. Their descendants, the modern pueblos, would not exist today if they had failed to sustain themselves and survive in climate variations much like what we are experiencing over recent years.

There are many useful lessons to be learned from these sustainable and resilient communities of the past in New Mexico and the rest of the Southwest. In a 2006 book published by UNM Press called Canyon Gardens: The Ancient Pueblo Landscapes of the American Southwest, landscape architect Baker Morrow and myself compiled essays from experts in pueblo culture and adaptive strategies for surviving in the harsh high desert climate of our region.

Those lessons include what might be called a textbook checklist of admonitions drawn from observations of Ancestral Puebloan/Pueblo landscape and site planning that relate to both building and agricultural practices.

They include:

- Never miss an opportunity for the benefits of any solar energy and heating.

- Minimize exposure to cold and wind.

- Make sure the most vulnerable connections and weakest links are overbuilt or redundantly reinforced.

- Allow the landscape to tell you where and what to build.

- Adopt a survival view of water and adapt yourself to it. (Canyon Gardens pages l76-77)

When it comes to agricultural resiliency in a difficult arid climate, ancestral puebloan peoples were experts at squeezing out every drop of water the land and sky could give them.

Pueblos across the centuries learned where all the available water was, learned how to use it efficiently and to waste as little as possible. They understood and used a wide variety of mulches, cultivated plants suited to their ecosystems, learned how to feed springs with snow, how far water would move out from a canyon mouth to cultivated fields, how high water usually gets in an arroyo for planting on its banks. They learned how to find seeps, how to slow down flooding water so it sinks into the soil and aquifer and disperses into small pools or moves through systems of canals. And everywhere water was, or everywhere they could deliver it, they planted the crops that would work the best. Redundancy was their strategy for growing food. Plant as much as you can everywhere you can so if one microclimate goes wrong you always have many backups to replace the lost crops.

Pueblo farmers paid attention to what was necessary—the whole range of ecological and climatic possibilities in their territory. Ignorance of how the land works and how weather can be made to serve human needs was not the issue with them that it is with us. The understanding of water, and how to use it, was the core strength creating a flexibility that allowed pueblo peoples to prosper and survive agriculturally for more than 3500 years and on into the present. Their resilience also derived from their attitude of respect for natural forces, their intergenerational sense of responsibility, and their devotion to human beings living in harmony with the rest of existence.

I wonder if the modern Southwestern world has any chance of lasting half as long as they have? Perhaps, if we pay attention ….

Why We Love New Mexico: A Cosmopolitan State

When I first went to the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in l960, Mexico City was the most cosmopolitan place I’d ever been. To me it beat every big city I’d been to in the United States and Europe by a mile. Indios, mestizos, ricos of all stripes, artists and writers, farmers, vaqueros, along with Danes, Germans, Spanish, Portuguese, Americans, Canadians, Haitians, Koreans, Swiss, and English lived in a rich cultural mélange of architectural and creative genius. Their fine education system, their music and museums were as stimulating, exotic and purely beautiful as any others I’d seen.

But when I returned to New Mexico, and started to grow up, I came to see that our own diversity and cultural hybrid vigor could compete in cosmopolitan élan with most any place in the world. By cosmopolitan I don’t mean the image of swank, jet-setting pretension, but that sense that the human cosmos, the whole world of humankind, expresses itself with particular vibrancy in New Mexico.

I think it’s hard for many, at first, to experience that human richness and diversity here because New Mexico is so large and its population so small. But after awhile one begins to realize that there are more than a dozen major museums in this poor and distant state, that the world of music is passionate and richly varied here, that we place an enormous value on higher education, that our cosmopolitan mix of human cultures and languages is unprecedented in the United States. Nine native languages and cultures combine with acequia and Chicano culture here in such a way that we are the heartland of both Native American survival and indigenous Hispanic culture. Our African-American communities are rich in tradition and one of the world’s great jazz and classical pianists, John Lewis, grew up and was musically inspired in the John Marshall neighborhood in Albuquerque. There are more painters and writers and poets and world class photographers in New Mexico per capita, it seems, than anywhere else. We have an abiding fascination with architecture and urbanism that’s rooted in Pueblo and Hispanic forms, as well as modernist adaptations to Southwestern conditions. We are still a rural state with powerful farming and ranching interests and an abiding cowboy culture that informs and strengthens many of our people. The mining and extractive industries here, many of them locally based, have a long history of political power as well.

When you add all this to our dominant presence in the scientific community with our scientific national labs, our astronomical facilities, our solar and wind technologists, our think tanks such as the Santa Fe Institute working with complexity and chaos theory, our environmental NGOs like the nuclear and environmental watchdogs at the Southwest Research and Information Center and the Southwest Organizing Project in Albuquerque and Conservation Voters New Mexico and other groups in the north, New Mexico’s culture becomes quite obviously cosmopolitan. And this is not mentioning our status as a refuge for people fleeing oppression and disruption in other parts of the world, our Latin American immigrants, our Vietnamese, Laotian, Thai, and Chinese populations, as well as our foreign scholars and students at our universities.

Once you begin to realize that virtually the whole world is represented here in astonishing abundance, that so much of the human cosmos thrives in the hugeness of our landscape and in the intimacy of our neighborhoods and communities, it dawns on you why other places in the country seem so monochromatic, so overwhelmed by consumer culture, and why we are always so happy to leave them and come home to the glorious human profusion which is ours.

(Photos: Acoma Pueblo reservoir / Public Domain; Northern NM Mountains by Ron Reiring / CC; ABQ Railyards market by osseous / CC)

Responses to “Provincial Matter, 5-4-2015”