During recent trips to the Mexican borderlands and into central Chihuahua, I have been accumulating stories of a rapidly escalating water crisis – of farm wells going dry, new wells being drilled to unprecedented depths (more than 300 meters), desperate residents of the poor colonias of Juárez and Chihuahua complaining of their increasing lack of water to drink and cook with, reservoirs drying up at an alarming pace, drought-stricken Tarahumaras coming down from the parched mountains, and ranchers letting their cattle die on the range.

Most everyone laments that never before have they seen such an intense drought. “Not in my life.” “Never before in our history.” “The mountains no longer bring the rain, and the land is dead.” I heard these and similar complaints, again and again.

Lately, however, the anxiety on both sides of the border has become more acute. Talk has turned from the usual observations and complaints about the region’s aridity to reflections about scarcity and survival. Whether from personal observation or obsessive reading of the latest research, the acceptance of climate change is altering the discussion and putting people on edge.

Climate Change in Mexico is Not Ideologically Charged

The acceptance of climate change in Chihuahua is a revelation.

Cambio climático (climate change) comes in declarative sentences without any ideological, political, or even scientific trappings. When talking about water or ranching, it is a term that usually comes in the first sentence of any discussion.

It is strangely liberating to hear the phenomenon of climate change simply stated and accepted – free of the ideological frameworks constructed by all political sectors across the border. Only miles apart – Deming, NM / Ascención, Chih or Columbus, NM/ Palomas, Chih. – the depth of the consensus about the threat of climate change is a more dramatic divide than the rise of the new 18-ft. border fence between south and north.

There are no surveys or science to document this divide in the perception of the new global reality. Clearly the conservative ideological backlash against climate change (which has no parallel in Mexico) is a factor. More important, however, may be the less intellectually refracted, more personal understanding of climate change as a threat to survival – seeing or envisioning a habitat without little or no water and with more extreme weather events.

Throughout Chihuahua the acceptance of climate change as the driving force behind reduced precipitation, higher temperatures, and longer and more intense droughts has led to a surge of new thinking by visionary homeowners, community leaders, and ranchers about environmental sustainability and survival.

Both the federal and state governments deserve credit for unconditionally identifying climate change in reports and public education materials about water and other natural resources. While government in Mexico – in marked contrast to the U.S. government – is unequivocal about the threat of climate change, it has done little to address the challenge or to enforce regulations that would result in more sustainable uses of resources, whether water, forests, or land cultivation and grazing.

Chihuahua’s Future At Risk

Like many observers of rural development, Martín Solís Bustamante, leader of the El Barzón organization of small farmers in Chihuahua, points to climate change as the most serious threat to the rural economy and society. “The number one problem we face is climate change, which is increasingly ravaging the country’s northern regions,” Solís said matter-of-factly during an interview in Chihuahua City.

It was June 30, the day before the presidential election in Mexico. But the presidential contest wasn’t mentioned during our conversation.

Like so many other close observers of rural development and environmental conditions in Chihuahua, Solís is preoccupied by the frightening acceleration of the region’s crisis. “The future of Chihuahua is at risk,” he said, as the interview came to a close. “Rural Chihuahua especially is threatened, and in as few as five years the rural economy -- ranching and farming – might shut down if we don’t do something now,” he added.

According to Solís halting the proliferation of new deep wells by Mennonite farmers, the massive transfer of ranching land to agriculture, and the failure of the government to enforce the laws regulating the exploitation of surface and ground water were the three problems about which something could be done. Climate change would continue but rural Chihuahua could survive its ravages if the people and the government took collaborative action.

The near-doomsday perspective of Solís contrasted with the business-as-usual view of Melchor López Ortiz, the regional director of surface and ground water at the National Commission of Water (Conagua), who assured me that the alarm about an imminent water crisis was not well-founded. Opening up Conagua website, López demonstrated the wealth of information about wells and dams that the federal agency collected and managed.

What about all the new wells – most over 800 feet deep – that were popping up all over Chihuahua, mostly on ranch land newly acquired by Mennonite communities?

“Yes, it is true that the Mennonites often disrespect Mexican laws, “ López acknowledged. “But they are highly productive and good for Chihuahua,” he said.

On my own travels along the New Mexico-Chihuahua border -- where there are three Mennonite colonies with vast agricultural operations in the desert – and elsewhere in Chihuahua, I had seen hundreds of new wells and only a few of them seemed to have the required permit. Conagua’s López assured me that agency inspectors investigated all such allegations, and it could not be faulted for permitting new wells on ranching lands that would be henceforth dedicated to farming since that permitting process was the responsibility not of Conagua but of Semarnat, the federal environmental ministry.

It is a well-known fact – and readily observed one – that there are many hundreds of new wells for farming in Chihuahua. Yet neither the federal government (which imposed the vedas in many areas of northern and central Chihuahua) nor the state government has demonstrated any commitment to ensure this explosion of new agribusiness doesn’t endanger the sustainability of ground reserves or the flow of surface water into the many government-constructed dams built since the 1950s in Chihuahua.

Taking the Rule of Law Seriously

Over the past month a new political dynamic has taken hold in north-central Chihuahua.

At first glance, this social turmoil over water resources is simply another case of the lack of “rule of law” in Mexico – and of Mexicans taking the law into their own hands. But the leaders of El Barzón, the small farmers organization, that shifted the dynamics of water policy with its operations shutting down illegal wells and dams, make a persuasive case that they are simply helping the government to enforce the rule of law.

As we sat at a Mennonite café the morning of the July 2 “operation” that set off the new politics of water in Chihuahua, Heraclio Rodríguez, a local farmer associated with El Barzón, “We see a future without any water, and when we go out today to shut down the illegal wells and dams, we aren’t breaking the law. We are doing the government’s job.”

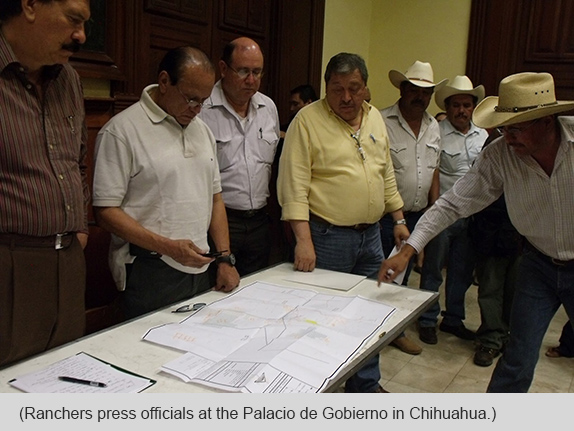

About ten hours later, facing a room of angry farmers, top government officials accepted the logic of that argument, agreeing to establish a joint farmer-government commission that would spearhead a new government initiative to shut down the illegal wells and raze illegal dams that were largely responsible for the precipitous drop of ground water levels in three Chihuahua municipios (counties).

An indisputable victory for El Barzón, and arguably one for the rule of law in Chihuahua. But in Chihuahua, as anywhere else experiencing the ravages of climate change, optimism is hard to come by, considering the apparently rapid advance of the impacts from climate change.

In Chihuahua, the lack of reliable information about the size and depletion rates of the aquifers also complicates an assessment of the severity of the current crisis, as does the systemic corruption and lack of transparency and accountability at all levels of government.

Nevertheless, the scene at the Palacio de Gobierno in Chihuahua on the night after the presidential election was auspicious. A previously recalcitrant, unresponsive government water bureaucracy yielded, at least temporarily, to a popular movement with facts and reason on its side.

Responses to “Politics of Climate Change in Chihuahua”