If you are my age and had a public school education, you may remember being forced to memorize poetry that you neither understood nor could relate to your life. Or, the experience may have been so negative you can’t remember it at all.

I vaguely recall Henry Wordsworth Longfellow’s “The Song of Hiawatha” and Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven” in the singsong inflections of a middle school teacher whose name I can no longer bring up. I now recognize the power in the second poem, but nothing about the way I first experienced it back then gave me access. As a student, I hated poetry. I never would have imagined that just a few years later I would decide to make it my life. That happened at a party in the East Mountains, where listening to a poem read out loud changed my sense of what poetry is—and my relationship to it.

Poetry is taught better today. But it remains the poor country cousin of the arts. Most parents don’t encourage their children to grow up and be poets. And even those who passionately embrace the genre know they most likely won’t be widely read or able to make a living at it.

Worse, the genre, at least in the United States, is considered esoteric, beyond the reach or interest of ordinary people. In many countries poetry occupies a central place. Poetry performances draw huge crowds. I myself have read to audiences of hundreds in Nicaragua and close to 5,000 in Colombia. Here, except for a few very well-known poets, audiences are small.

This is one of the reasons I found the Women of the World Poetry Slam to be so exciting. There were other reasons as well. The event is international and its eighth edition took place in Albuquerque March 18 through 21, 2015. Women of the World emphasizes young women’s empowerment through creativity. Even in the rarified atmosphere of the genre, male voices continue to outshout their female counterparts. And older, more established, authors predominate over younger voices. Publication, invitations to read, grants, inclusion in anthologies: all of that is biased toward the male voice.

Women of the World takes all that inequality and turns it on its head.

Albuquerque is an ideal place for such an event to be held. Our poetry scene has long been known for its richness and inclusivity. We have many more ongoing poetry venues than cities twice our size. Poets who visit from elsewhere tend to be astonished. Albuquerque also has an unusual number of excellent poetry journals—among them Mas Tequila Review, Malpais Review, and Adobe Walls. The city draws poets from other places, to live as well as to read. But perhaps most unusual is the fact that readings here often combine slam and page poets, performance poets and those who read more conventionally. A commonality of mutual support permeates these events.

I was privileged to be invited to give the keynote address at this year’s Women of the World Poetry Slam. The auditorium at the Indian Pueblo Cultural Center was standing room only, and the atmosphere similar to that in a Black church where every gesture or exclamation by a performer was greeted by vocal signs of affirmation from the enthusiastic audience. I’m sure everyone else who took part also experienced that wonderful feeling of connection and gratitude.

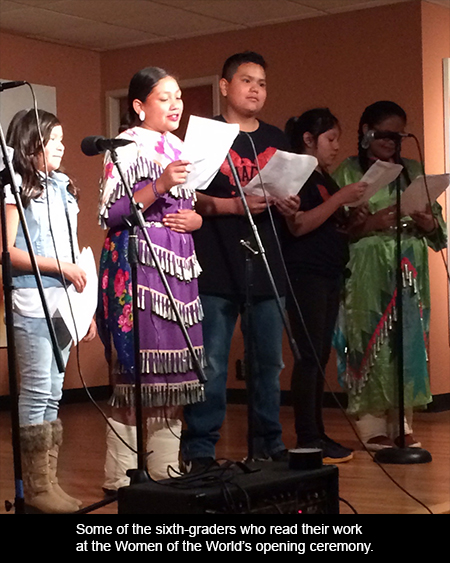

A heartfelt blessing was offered by four women from different indigenous communities. A beautiful jingle dance followed, performed by sixth graders from the school across the street. Their teacher, who also participated, explained that the school occupies the last building standing of the nefarious boarding school that once functioned there.

The next treat was brought to us by Albuquerque’s current poet laureate, Jessica Helen Lopez, and was a vivid example of her work in our community. A group of young NACA poets read their poems in English, Spanish and Diné. Each poet read a short poem of her or his own, but their companions joined in reading certain stanzas. The poems were original, fresh, filled with pathos and humor, and occasionally surprising.

Covering one wall of the auditorium was a large chalkboard titled “I Write Because.” Again, in English, Spanish and Diné, participants had filled in their own conclusions to that phrase, and festival organizers urged more to do so. This board, as well as the whole feel of the event, was a constant reaffirmation of young women finding and projecting their voices, naming themselves and their needs, telling their stories and painting their dreams in words only each of them could own.

And there were also young men in this audience, vocal and affirming in support of their female comrades.

Rarely have I seen such a large group of young people so integrated in terms of race, gender, and age. Indigenous, Chicana, African-American, Anglo, queer and transgender poets took the stage during the Slam’s four days of activities; and issues such as violence against women, community building, reproductive justice, and cultural humility were important themes.

The Women of the World Poetry Slam is a four-day festival, in which 72 of the best female poets in the world compete against each other over two nights of preliminary competitions, referred to as bouts. A slam poem is generally limited to three minutes. The poets with the top twelve scores from those first days move on to the finals, where one poet is crowned the champion. In addition to this slam competition, each day of the festival features poetry workshops, themed open mics, special nighttime events, and the inevitable parties.

Bookworks on Rio Grande, the Pueblo Indian Cultural Center, Stereo Bar, Downtown Flying Star Café, Tricklock Performance Theater, Tractor Brewing, Albuquerque’s Main Library, El Chante Casa de Cultura, 516 Arts, and the Moonlight Lounge were all well attended venues for the Slam’s variety of events.

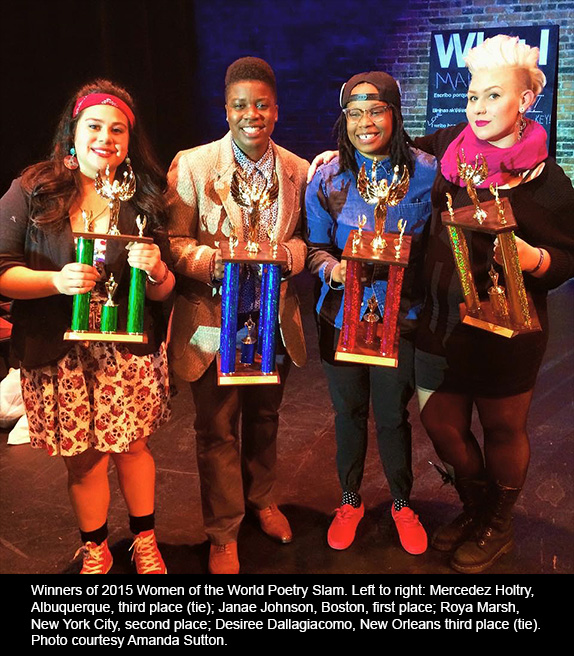

Seventy-two young women poets, most of them from the United States, compete in each year’s Women of the World Slam festival. That number is reduced to 12 finalists, who this year were Roya Marsh, Desiree Dallagiacomo, Mercedez Holtry, FreeQuency, Janae Johnson, Samira Obeid, Taylor Steele, Confidence Omenai, Kwene, Miss Haze, Amantha Peterson, and Angelique Palmer. One of this year’s finalists, Mercedez Holtry, won the ABQ Slam finals in December, 2014. Holtry attended Albuquerque High School, which she said has a terrific poetry community.

The great finale took place at the Kimo Theater on March 21. There was a full house, and social media was lighting up days prior with people trying to obtain last-minute tickets. Any one of the twelve finalists could have won; they were all that good. Judges scores for all ranged between nine and the maximum 10. Content varied, but empowered womanhood shone among the contestants, whose words embodied a deep knowledge of what it means to be a woman today, bristled with originality, and elicited excited approval from the rapt audience. The atmosphere was electric. The 2015 winner was Janae Johnson of Boston, Massachusetts.

Interestingly, in contrast with that rote memorization that made an introduction to poetry so meaningless back in my school days, slam poets today also memorize their poems but the two experiences couldn’t be more different. This new memorization is hot, alive, buzzing with feeling and aided by the music of a loudly beating heart.

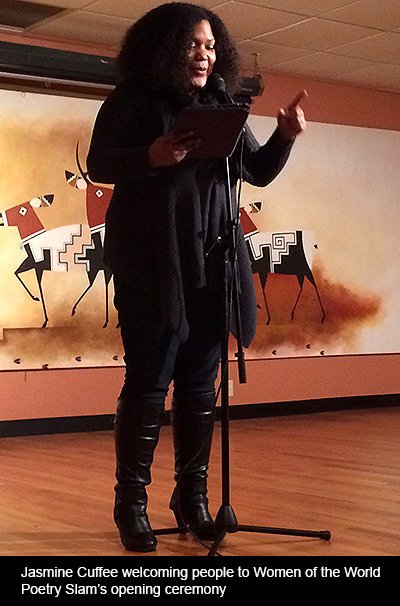

Jasmine Cuffee was the chair of this year’s magna event. She said the Slam is not just about poets getting together and reading poetry, but “creates a space for poets to share their voices with us. We’re creating a new audience for poetry and poetry lovers. The festival events also create a space where we can honor women’s voices and stories honestly and openly,” she added.

A core committee planned and worked for more than a year to bring this event to fruition. Besides Cuffee, the planning committee included Erin Northern, Katrina Guarascio, Amanda Sutton, and the city’s poet laureate Jessica Helen Lopez. These women, and everyone else who pitched in to make all the venues so successful, should be commended for helping young women find their voices and bringing their poetry out of the shadows.

Responses to “Poetry Finds a Future: Women of the World Poetry Slam”