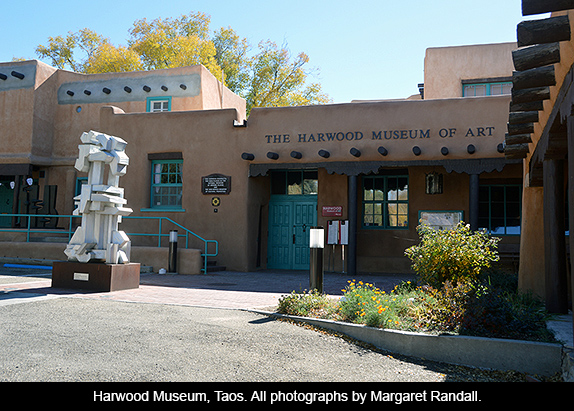

Órale! Kings & Queens of Cool, currently at the Harwood Museum in Taos, combines four interrelated exhibits: Lowbrow Insurgence: The Rise of Post-Pop Art, Nuevo Lowbrow: Pop Culture In The West, Pinstripe Madera: Pinstripe as Minimalism; and El Tatuaje: The Tattoo in Underground Culture. They are perfectly braided in form and content, and will be open through January 25, 2015. Órale’s English translation might be anything from hey to wow. In this case the latter meaning is the most applicable. The interconnected show wows the viewer with its rich iconography and eye-stopping color.

It also asks a good many questions.

Jina Brenneman was the exhibition’s main curator, and her words in the catalog acknowledgements are worth transcribing: “ […] it started with a Greg Moon exhibit I visited two years ago, and loved. That led to the introduction of co-conspirator and co-curator Dennis Larkins. Dennis had all of the high-end/low-brow white boy connections one could ask for. To make this exhibition relevant in New Mexico, though, we needed brown.” Brenneman goes on to describe a lowrider show in Española where she made other contacts and would eventually meet many of the artists she would eventually feature. A friend in Taos told us this exhibition was Brenneman’s swan song at the museum: “She left soon after it opened,” he said, “I hope of her own desire, and that she’ll go on to do other important things.”

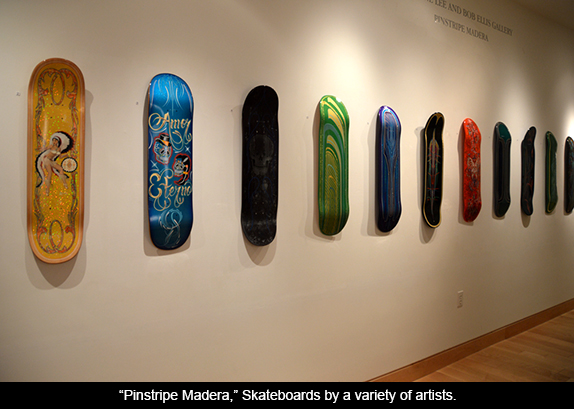

The catalog, itself a work of art (designed by Esteban and Karen Bojorquez), describes the included artists as “[making] art on whatever canvasses they can find.” You know: billboards, subway cars, the sides of abandoned buildings, human skin, or the bodies of dressed up automobiles that began promenading slowly along our city streets at night or rose on their haunches like intricately painted pre-terminator machines beginning in the late 1970s. Española, New Mexico considered itself the lowrider capital of the world back then.

This art, descendant of Pop and Post-Pop or Lowbrow art, grew out of the West Coast surfer, street and car cultures. It would seem to have risen in opposition to the schools that preceded it: Impressionism, Cubism, and Abstract Expressionism among others. Part of its bravado resides in its use of found materials and apparent disdain for the acceptable nuances of the more traditional forms and for the rules of a highly commodity-centered art world. Its artists often started out “defacing” public or private property. Only when the official art world’s makers and breakers discovered their originality and talent, and realized that a profit could be made, were some of these “street artists” invited to paint on provided surfaces and show in galleries and museums. Today many of them command high prices.

So, the message is often macho, violent, and highly commercialized, even while profoundly critical of the status quo. Danger (going out at night to leave their vibrant mark on public property, always risking being persecuted by the police and society at large, attacking the “sacredness” of property whether public or private) was there in early manifestations, and its aura remains. As many of these artists gained recognition, their modus operandi ceased to include this sort of risk. But the aura has left its mark on subject matter and style.

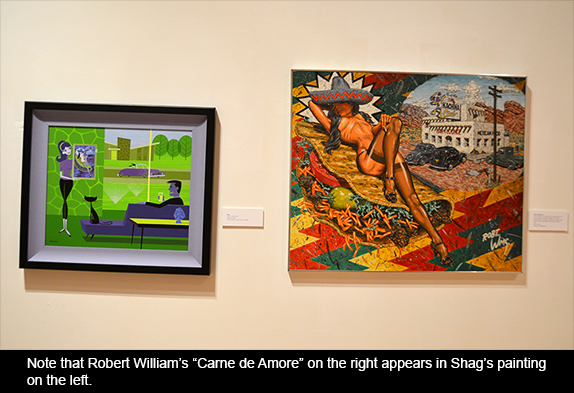

The kings and queens of cool draw their inspiration from a long list of predecessors: pop artists Jim Dine, Jasper Johns, Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Shepard Fairy, and of course Banksy. Fairy is best known for his image of Barack Obama, later reproduced on a postage stamp. He comes not from the street but out of the Rhode Island School of design, as do others now that the genre has been recognized. Banksy, from England, may be the best-known street artist around, as much because of his carefully preserved anonymity as his immense talent. The Harwood shows, however, embody distinctly West Coast and New Mexican flavors. Ed Roth was an early icon of this part of the movement, as was Robert Crumb. Albuquerque-born Robert Williams, a contemporary and colleague of Crumb, is featured in this show.

Some women have also made their mark in this outsider movement. Lady Pink began tagging at the age of 15, and remains one of the few female artists we hear about in this rich international field of men. Caledonia Dance Curry (better known as Swoon) and Polish-born Olek are also stars among the women. Olek uses the traditional female art of crocheting in her work; the Smithsonian recently had a show of hers that featured the entire contents of her apartment depicted through crochet.

The number of women represented in this show makes it only slightly more gender equitable than exhibitions in our museums have been for decades. Given the macho nature of much of the culture that produces this art, though, the fact that there are as many women as there are might be applauded. Of course it’s almost impossible to sink as low on this score as most of our major museums still do, where a 100 to 1 ratio is the norm. I especially liked works by Lisa Petrucci, Camille Rose Garcia, and Margaret Kasahara, but was unable to photograph them because of glare.

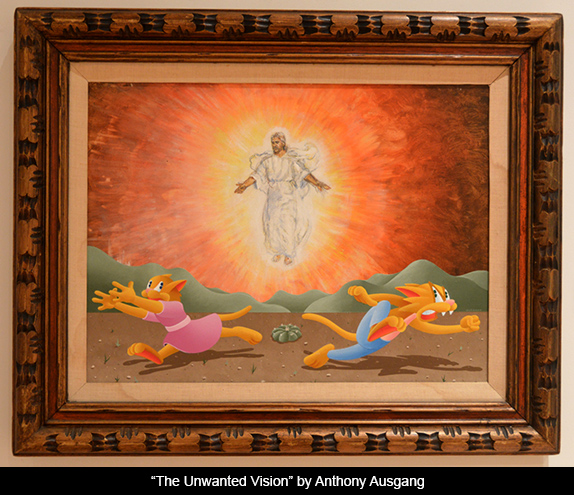

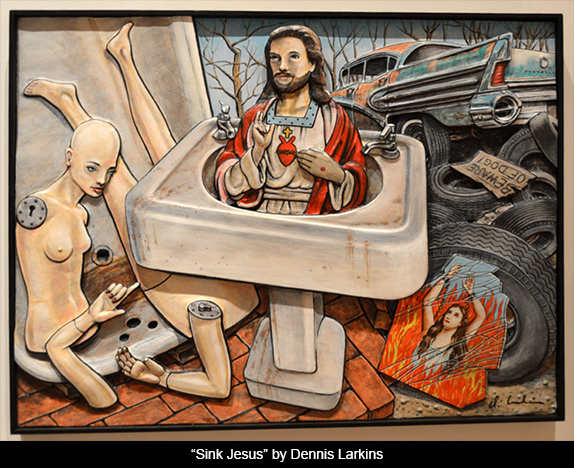

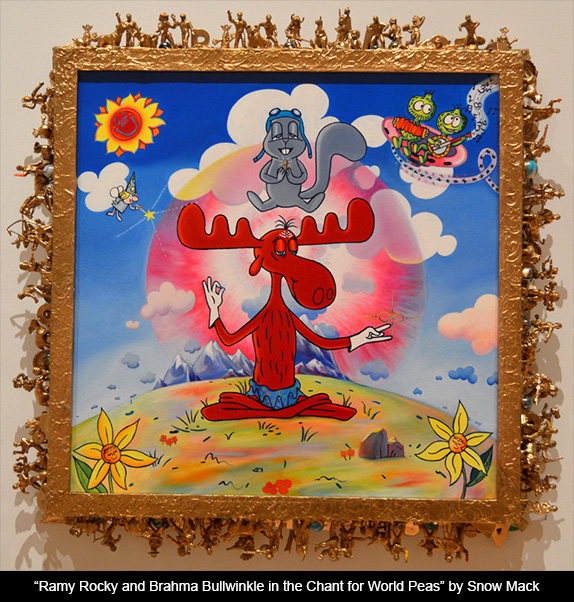

The lowbrow movement, a distinct underground fusion from southern California in the 1970s, has underground roots in hot rods, and comics as statements on the overall consumer society. It prides itself in its anti-art establishment’s flouting of traditional art world etiquette. But this art also draws upon ancient petroglyphs, medieval triptychs, mandalas, religious retablos and milagros, Navajo eye dazzlers and sand paintings, beadwork, stained glass windows, quilts, and masks. Surrealism and hyperrealism. The Mexican muralists and their US inheritors. Day of the Dead. Architecture and clothing mannequins. Comics, graphic novels, family stories and heroic characters. The grotesque as art form, horror films, gang signs, videogames, and lowriders. The psychedelic experience. Poster art, calendar art, and commercial advertising and signage. Calligraphy, tattoos, graffiti, television, computer graphics. Photoshop. Objects of everyday use and whatever happens to be going on inside the artist’s rebel mind and spirit. The visionary, whether by way of drugs, meditation, or other heightened experience, is definitely present. It would be easier to make a list of that which is not represented.

This work embodies satire and subversion. It doesn’t whisper, but shouts. A particular work may attract through sheer beauty of design, grotesquery of image, raucous humor, or ability to shock. In some pieces, a sustained gaze reveals images half hidden within images, like the glyphs within glyphs on Mayan stone. Surprises abound. The Harwood’s interconnected shows feature original comic strips alongside altars of reverence and an installation in which the chairs where a tattoo artist sits beside a customer (you can almost see them inhabiting those chairs) appear before a wall of traditional skin art designs with a sign advertising the art.

One of the immediately assumed differences between this art and past artistic manifestations is the use of found surfaces rather than carefully stretched and primed canvasses—although many of the works in these exhibitions are painted on canvass and most are beautifully framed. Another difference is subject matter. These artists find theirs in everything from comic characters to industrial design, moving through religious iconography and psychedelic imagination. These differences, of course, disappear upon closer examination, telling us that the kings and queens of cool aren’t that different from Michelangelo, Picasso, Pollack or O’Keeffe. Fifteenth century Hieronymus Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights” would be right at home among these paintings.

Once we get past the barriers erected by ignorance and prejudice, other differences also begin to erode. Contemporary concerns, talent, elegance and fine craftsmanship combine to produce street art that lifts the hasty and crude to levels of masterful authorship. By the time this sort of work makes it into galleries, onto museum walls or to high-end auction houses, we are looking at its most brilliant exponents. Despite claims to the contrary, these artists currently compete with their more traditional counterparts for a share of the overblown art market.

There are also some real differences between this art and its predecessors. Street art exploded into the public consciousness largely in Chicano and Latino neighborhoods. It might be said, with exceptions that only confirm the rule, that it constitutes a profound contribution by a population that will soon be the national majority but still suffers more than its demographic share of inequities: exploitation, derision toward its multiple cultures, a history of oppression, attacks on its language, lesser educational opportunities, lower paying jobs, and a general lack of respect. Class, race, ethnicity, and the immigrant experience are all powerfully present in the work.

Another difference is surface. It was artists such as Haring and Banksy who first began making a statement about public space vs. less popularly accessible museum walls by painting on sidewalks, buildings and other available spaces. A trip to New York’s Museum of Modern Art currently costs $25.00. These artists not only appropriate public space, they paint on objects of ritual use such as lowriders and skate boards.

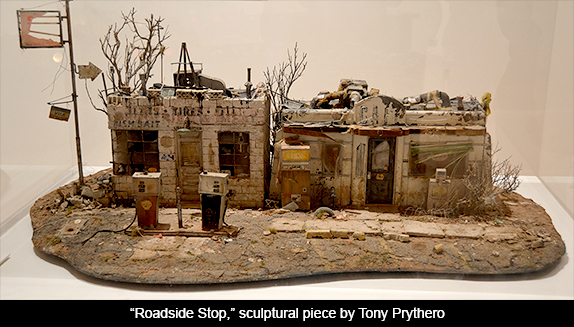

To me, one of the show’s most fascinating pieces is the sculptural model by Tim Prythero titled “Roadside Stop.” One can circle the work, which depicts a decaying store and gas station, complete with abandoned pumps, badly patched heating ducts, trees growing out of an eroding foundation, a signpost whose sign is completely gone, an open-doored refrigerator filled only with the imprint of food, and a rotted mattress peeking out from behind an accumulation of yesterdays. This is memory made three-dimensional. And this roadside stop could be Anywhere, USA. At first glance it evokes the obvious sad decay of a culture we cannot save. But its perfect detail speaks a nostalgia that provokes a dozen questions.

Once again, the art is more complex than it might seem at first glance. The works in this exhibit take a variety of cultural symbols and turn them on their heads, or reveal their innermost contradictions. In an era when test-taking replaces critical thinking, revenge passes for patriotism, war is billed as necessary to bring about peace, democracy goes to the highest bidder, violence prospers, and too many of our leaders remain in denial about the fate of a planet besieged by climate change, this may be the artistic genre that most clearly tells it like it is.

One explicit difference between this exhibition and those presenting other artistic genres is these artists’ disinterest in speaking about their work, a lack that is reflected in the otherwise beautiful catalog. There are no artist’s statements or texts about their work, or about street art in general, no essays by critics to tell us what we should think about this art or push us to revelations and useful connections. There’s not even any biographical material, which I for one would have appreciated.

In fact, belying the claim to non-commercialism, the only text of any length in the catalog is a piece by the director of La Luz de Jesus Gallery, Matt Kennedy. It is about collector Billy Shire and his 50-year impact on the genre. It’s an interesting story, no doubt about that, but I would have loved hearing from at least some of the artists, learning about where they come from, how they began making their art, and especially how they moved from rebellion to the marketplace.

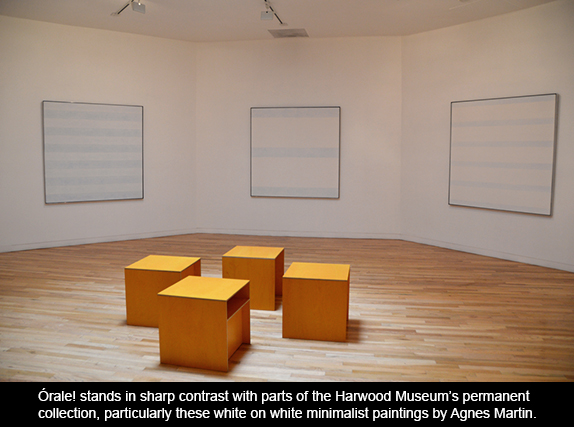

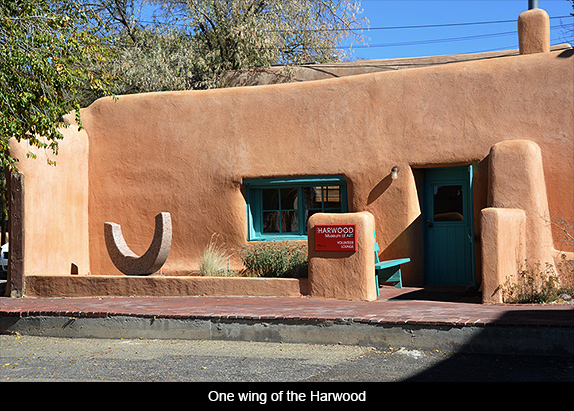

The Harwood Museum is a well-designed and gracious space in which to view art. Its permanent collection is rich in paintings by those artists commonly considered part of the Taos artist colony: Ernest Blumenschein, Joseph Henry Sharp, Cordelia Wilson, among others; and later Agnes Martin and Georgia O’Keeffe, although the latter only briefly visited that group that was anchored by writer D. H. Lawrence and art patron Mabel Dodge Lujan, and she eventually settled farther south at Abiquiu.

The Harwood also has a beautiful collection of santos and other regional religious iconography, and some period furniture. The hexagonal gallery displaying six large minimalist white on white paintings by Agnes Martin contains a perfect group of yellow viewing stools by Donald Judd.

But visiting the Harwood today, one is definitely wowed by Órale! Viewing the permanent collection is worthwhile even as its treasures fade alongside these vibrant manifestations of an art that reflects the content, style, and contrasts of a society struggling to grapple with its most blatant contradictions.

Responses to “Órale! Post-Pop Fusion at The Harwood”