Although it is not a Christmas Nativity scene, “The Holy Family” by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) provides a deeply personal meditation on the meaning of the season’s traditional “twelve days of Christmas,” which continue until the Eve of the Epiphany on January 5th.

Bracketed between the night of Christ’s birth and the arrival of the Three Kings or Magi, the twelve days of the Roman Catholic tradition celebrated in the villas and pueblos of New Mexico include the Feast of the Holy Innocents on December 28 and the Feast of the Holy Family on December 30. Both of these, in a broad sense, enter into Poussin’s meditation, as does the Baptism of Christ, which is celebrated on the Sunday following the Epiphany, or the “showing forth” of the Christ Child to the gift-bearing Magi on January 6th.

I first became fascinated with Poussin’s wonderful painting while working at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles in the 1990s. Once in the collection of the dukes of Devonshire at Chatsworth in England, the picture is now jointly owned by the Getty and the Norton Simon Museum, who collaborated on its purchase in 1981 and who share it on a rotating basis.

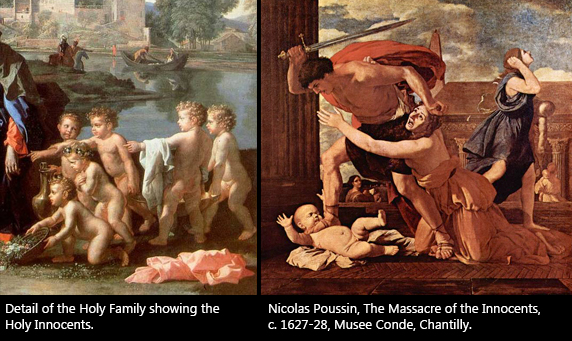

In the spirit of the season, Poussin depicts an intimate family gathering centered around children. As parental figures quietly look on, the Christ Child and the infant John the Baptist embrace in a joyous greeting. Beside them, like a rippling echo multiplying their youthful happiness, a bevy of small boys bustles in, bowing, bearing gifts of flowers, and lugging a large brass basin for the Christ Child’s bath, a prefiguration of his later baptism by John.

With its busy abundance of baby flesh and fresh linen, Poussin’s picture recalls Jesus’s familiar words: “Suffer the little children to come unto me, and forbid them not: for such is the kingdom of God.” To which he adds, “Whosoever shall not receive the kingdom of God as a little child shall in no wise enter therein,” reiterating humanity’s common need to regain lost innocence. The painting’s theme, then, is nothing less than the renewal of the world.

Behind this theme, as with the Advent season itself, is the chilly winter of our discontent—that profound human longing for rescue from the darkness of guilt and remorse that can seem to close in unbearably as the days grow short. Surely it is no coincidence that Christmas occurs in the calendar just after the winter solstice, the darkest time of year, when the light, which had been steadily receding since mid-summer, begins miraculously to return.

Yet Poussin’s painting is full of warmth and springtime regeneration as it opens into a sunlit Italian landscape. And while he has closely followed the Church doctrine of his day, incorporating it into even the tiniest details, he has also personalized his subject in a most unexpected way. This personalization is in fact so surprising, and so out of character with Poussin’s reputation as an artist of cool formality and rational detachment, that it has, so far as I know, gone entirely unrecognized.

As a young man, Poussin forsook his native France to settle in Rome. There he immersed himself in the lingering legacy of ancient Classical civilization and absorbed the great masterworks of the High Renaissance, particularly the art of Raphael and Titian. Although the art world of his time was dominated by the ecstatic Baroque dramas sponsored by the Counter-Reformation Church, he became a leading exponent of Classicism, a style of art characterized by clarity and rational order.

“Signor Poussin is a painter who works from up here,” said the great sculptor Bernini, tapping his forehead, and Poussin has always been esteemed for the intellectual qualities of his art. He sometimes spent months mulling over a subject to come up with what he called a “pensée” (“thought” or “concept”) for its presentation.

But, like a modern “method” actor, Poussin also immersed himself in his subjects emotionally. Once, having just completed a painting of the “Crucifixion,” he refused a patron’s request for a “Bearing of the Cross,” claiming, “Just now, I couldn’t stand up against the solemn agonizing thoughts with which one must fill one’s heart and mind when dealing with subjects so sad in themselves.” So perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to find him personalizing the “Holy Family,” projecting himself into its meaning.

The legendary meeting between the boy Baptist and the Christ Child emerged as an elaboration of Matthew’s account of the visit of the “Wise Men from the East,” who came following a star. In the aftermath of the Magi’s journey, the jealous King Herod determined to destroy the newborn king and savior they sought and sent his soldiers to murder all the male children, two years and younger, in the district of Bethlehem. To escape this Massacre of the Innocents, the Holy Family undertook the Flight into Egypt. It was during this exile, according to later commentators, that they supposedly encountered the young St. John, whose aged mother, St. Elizabeth, had likewise saved her six-month-old son by fleeing into the wilderness.

Poussin’s painting basically depicts the Flight into Egypt, regrouping the fugitives as wayfarers resting at a roadside well.

The meeting of the two holy children became a favorite subject of Renaissance artists and patrons because it represents the pivotal moment when the Old Testament gives way to the New. John is the last of the old-style prophets, the one who recognizes the foretold Messiah. In Poussin’s painting the little St. John holds a ribbon inscribed with the words “Ecce agnus dei” (“Behold the Lamb of God”), identifying Christ as the sacrificial lamb who redeems the sins of the world.

In the Gospels, of course, this recognition happens later, when John baptizes Christ at the river Jordan. But in the fifteenth century a poetic retelling of the story was invented, recasting the scene with two tender infants to underscore its message of the world’s renewal.

All children, of course, represent the renewal of the world in the innocence and potential of a new beginning, and Poussin elaborates on this by adding six energetic toddlers with a bath tub. It is a poignant addition, however, since these children are meant to represent the Holy Innocents slain by Herod. They are the flores martyrum, venerated, in the words of St. Augustine, as “the first buds of the Church, killed by the frost of persecution.” Having died at Bethlehem in Christ’s stead, the Innocents now bring flowers and a baptismal basin to prepare the ritual cleansing of the Child whose eventual sacrifice is destined to purify the world.

There can be no doubt that Poussin intends to remind us of the terrible episode of the Massacre of the Innocents. In the distance beyond the boys, he depicts two mounted soldiers, gesturing toward a couple who appear to be fleeing in a boat, which was a common way of showing the Holy Family’s flight into Egypt. In his earlier years Poussin had twice painted the horrific violence and suffering wrought by the slaughtering soldiers. But his reintroduction of the martyred Innocents into a traditional scene of the Holy Family’s Rest on the Flight into Egypt is highly unusual.

Poussin was probing for the larger meaning of Matthew’s text. He understood that Matthew meant to show two things: that Christ’s coming was a clear fulfillment of Old Testament prophesies, and that the world remained hostile to God’s plan for its redemption. He also recognized that the introduction of John into the story brought up both the issue of sacrifice and the institution of the primary sacrament of the Church, the rite of Baptism.

For the Church, Baptism represents the washing away of the guilt of Original Sin, the inherited contamination that resulted from Adam’s disobedience and fall from grace. Consequently, in his painting of the Innocents with a baptismal tub, Poussin has turned the issue of sacrifice into a happy event—a confirmation of prophesy fulfilled¬¬ and a reminder that all has been preordained in God’s providential plan for the world’s salvation. (“For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten son.”)

In Poussin’s painting, the Innocents approach the Holy Family with the dignity of celebrants at a sacred ceremony. One of them, the most beautiful, wears the traditional garland of sanctity and of ancient pagan sacrifice in his golden hair. He bows with his arms crossed on his chest in a gesture of homage and humility that is often given to the Virgin as she humbly receives the Holy Spirit during the Annunciation.

It’s possible that Poussin means this boy to be evocative not only of ancient sacrifice and submission to Divine Will, but also of the medieval custom of electing a “boy bishop” on St. Nicholas’s Day (December 6) as an aspect of honoring children during the Advent season. Assuming his post during mass at the recital of the Magnificat (“He hath put down the mighty from their seat and hath exalted the meek”), the boy bishop held office through Holy Innocents Day (called “Childermas” in England) on December 28. Although the custom was dying by Poussin’s time, he may have witnessed it, perhaps even participated, as a boy growing up in Les Andelys in Normandy. Since it occurred on his name-saint’s day, its impact would have been all the more personally meaningful and memorable.

But one of the great mysteries of Poussin’s painting is how the innocent victims of manifest evil have been transformed into representatives of the abundance of Divine Love. Although they wear no “Cupid’s wings,” Poussin nevertheless derived his little attendants from Classical Greek and Roman sources, where they represented human affections inspired by Eros. During the Renaissance these little figures came to be associated with angelic spirits (cherubs). Called “erotes” in the ancient texts, and “putti” or “amorini” in Italy, their curious blending of earthly and divine love is still an indispensable component of our St. Valentine’s Day observances. Strewing roses at the Virgin Mary’s feet, they identify her with Venus, the pagan goddess of grace and love, whose ancient symbol was the rose.

In his dignified blending of the Classical and the Christian, Poussin has painted the Virgin as a Roman goddess and placed her in the exact center of his picture. To the French she is “Notre Dame” (Our Lady), and it is her role as the loving intercessor on behalf of humankind that the painting celebrates.

Poussin rendered her face as a porcelain ideal, and in his Classical approach to painting, faces are mostly generalized types. St. Elizabeth's elderly visage is a gray and conventional mask here, while the children are basically cloned from a single curly-topped moppet.

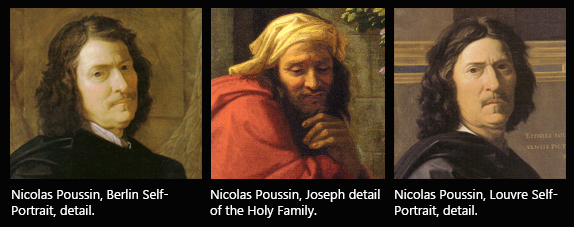

Joseph’s face, however, is distinctly different. While at first glance he seems like a stock character from Central Casting, when you look closely you find a surprising individuality. In a truly extraordinary move, Poussin has painted his own features, portraying himself as the Holy Child’s foster father.

I was quite shocked and skeptical when I first noticed this resemblance. Of course, seventeenth-century art is full of self-portraits. Rembrandt scrupulously studied his own features throughout his life, while Caravaggio and other artists slipped their faces into all kinds of dramatic compositions. Still others seized the occasion to reflect on studio practices and their own rising social status. During the same decade that Poussin painted the “Holy Family,” Velázquez depicted himself at work inside the Spanish royal household in what is perhaps art’s most dazzling meditation on the art of portraiture, “Las Meninas.”

But, unlike so many of his contemporaries, Poussin was notoriously reluctant to paint a self-portrait. When pressed to do so by his patrons he stewed around for more than a year, literally having second thoughts. In the end, he produced two quite different takes, the first of which is now in Berlin, the second is in the Louvre.

This prolonged period of self-analysis, however, occurred in 1649 and 1650, the years just preceding our Holy Family painting. And when you compare the two self-portraits with our Joseph, the shaggy hair, the forehead, eyes, nose and cheeks, and particularly the unmistakable upper lip, all exactly match. Even the shouldered fold of drapery is repeated!

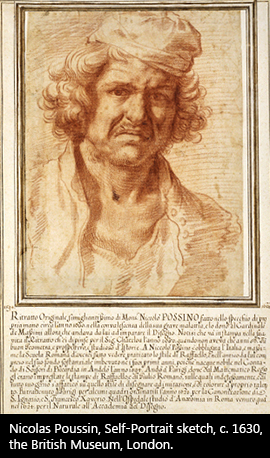

Poussin’s only other known self-portrait is a drawing, now in the British Museum. It shows a younger, somewhat distressed looking Poussin, and it provides a surprising clue to his unexpected appearance in “The Holy Family.” An inscription on the drawing explains that it was made in 1630 at a time when the artist was recovering from a serious illness.

Poussin’s only other known self-portrait is a drawing, now in the British Museum. It shows a younger, somewhat distressed looking Poussin, and it provides a surprising clue to his unexpected appearance in “The Holy Family.” An inscription on the drawing explains that it was made in 1630 at a time when the artist was recovering from a serious illness.

At age thirty-five, after years of suffering, Poussin was desperate with what a contemporary biographer called “the French malady”—an Italian euphemism for venereal disease. He was taken in by the family of Jacques Dughet, a French cook in Rome, whose sons would later join Poussin’s studio, and whose wife and teenage daughter, Anne-Marie, nursed him through the long and excruciating cure prescribed in his day.

In gratitude, when he was well enough, he married the sixteen-year-old Anne-Marie, who was less than half his age. Almost nothing is known of Poussin’s private life, except that while it was to be a long, devoted, and apparently happy marriage, it produced no children.

Poignantly, in our “Holy Family,” in a context fully burgeoning with babies and springtime renewal, Poussin gives special emphasis to the washing away of sins in the purifying waters of baptism.

In among the roses spilled at the Virgin’s feet are tiny blue flowers. These are hyssop, a curative herb sometimes used ceremonially to sprinkle holy water, referenced in the Miserere (Psalm 51): “Sprinkle me with hyssop, and I shall be clean; wash me and I shall be whiter than snow.”

Poussin’s most moving image of penance and the washing away of a contamination that one has somehow brought upon oneself is the Metropolitan Museum’s “Midas Washing at the Source of the Pactolus,” a scene that was probably painted about the time he undertook the cure for his illness. It was made as a pendant to his first version of the “Arcadian Shepherds,” and there may well be a connection between its theme of cleansing away the effects of misguided desire and the latter’s moral about the presence of death even in Arcadia. Midas had asked for the gift of the golden touch, only to discover its down side. And the young Poussin, practicing his golden gifts amid Rome’s Arcadian seductions and building his artistic reputation with bittersweet amorous subjects drawn from the poetry of Ovid, was himself brought to a sudden and unexpected confrontation with mortality.

Despite his youthful worship of Venus, she had nevertheless inflicted him with a near mortal wound. Now in his mid-fifties and likely seeking some reconciliation with his own childless fate, Poussin identifies himself with the adoptive father of the Holy Child. (“We have nothing that is truly our own,” he once wrote, stoically. “We hold everything as a loan.”)

Poor St. Joseph, long portrayed as a kind of earthy bumpkin, old enough to ensure the virginity of his wife and sometimes even ridiculed as the “Divine cuckold,” was undergoing a major rehabilitation in the seventeenth century. In its search for exemplary moral figures for parishioners to emulate, the Church of the Counter Reformation was promoting a new image of Joseph, proclaiming him to be a protective parent and an honest craftsman engaged in dignified labor.

The detailed account of Joseph’s lineage that begins the book of Matthew (1:1 – 25) shows him to be a direct descendant of King David and of his son Solomon, who built the Great Temple in Jerusalem. Thus the humble carpenter, given to dreams like his other namesake in the Bible, came to be seen as a builder, even a divinely inspired architect.

But it was only as recently as 1621 that Pope Gregory XV gave St. Joseph a distinguished place on the liturgical calendar, declaring March 19 as his feast day. And in a quite remarkable development, a society of artists in Rome, calling themselves the “Congregazione dei Virtuosi,” established an annual exhibition in the saint’s honor on that day.

Held in the portico of the Pantheon, where it would also honor the great artist Raphael, who was buried there, it provided one of the few opportunities for artists to show their work in a public forum. In those days there were no museums or art galleries as we know them. And indeed it was at that venue, known as “San Giuseppe in Rotunda,” that Velázquez caused a sensation during his sojourn in Rome in 1650, by showing his brilliant portrait of his servant, “Juan de Pareja” (now in New York’s Metropolitan Museum).

Poussin would almost certainly have participated in the “San Giuseppe in Rotunda” exhibit that year. In any case, it was during that same month (March 1650) that he announced to his patron Chantelou that his two self-portraits were completed and ready to ship. Thus he concluded his own unique involvement with portraiture—except that within a year his features would reappear in an unprecedented identification with San Giuseppe.

Is it possible that Poussin conceived his “Holy Family” painting in the spirit of the Virtuosi’s homage to San Giuseppe, perhaps even with an eye to presenting it at that important annual event?

From the time of St. Ambrose, a correlation between Christ’s Heavenly Father and his earthly father had been noticed in the verbal play on the Latin term “faber” (artisan or creator/maker/fabricator), which was applied to both. This typological pairing would have been common knowledge among the Virtuosi. It was spelled out in a popular treatise on St. Joseph by Fra Jerónimo Gracián (an associate of St. Theresa of Avila), which was first published in Rome in 1597 and was widely circulated in the seventeenth-century campaign to promote the cult of Joseph. “Just as Our Lord God has two names, the first being the ‘Father of Jesus’ and the second the Faber or ‘artisan’ who made and created the world, He found a faber, an artisan or carpenter, named Joseph, upon whom He bestowed the name ‘father of Jesus.’”

By casting himself as Joseph the Carpenter, flanked by a ruined building that traditionally symbolizes the world’s fallen state, its need for renovation, Poussin also personally assumes the role of “faber,” recasting the term as “architectus”—in two of its ancient uses. He is both the “master craftsman” and the “cunning steward” who stands behind the scene and sees to it that the Divine Plan of Salvation is properly revealed, ensuring that everything takes place as it was intended.

Yet, for all its sunlit warmth and tender joy, you sense an undercurrent of melancholy in Poussin’s picture, especially in the faces of the adults. It may be that their faces reflect a foreknowledge of what is to come—that the story culminates in the sacrifice of the child in their midst. Perhaps they also recognize that despite the promise of salvation won by that sacrifice, there is still this natural cycle of earthly life to be gone through.

The wheel of earthly time turns as our eyes move around these central faces, from the infancy of the two holy children, to the youth of the mother, the maturity of Joseph, and the old age of Elizabeth. In the face of Poussin/Joseph the melancholy is especially telling. While he clearly takes pleasure in the scene before him, his eyes turn away into his own thoughts. His gaze strays downward to the aged Elizabeth, so that our eyes, following his, are led on through the cycle.

To be alive is after all to be caught in the turning seasons of Nature and to experience the inevitability of disappointment and loss. “Et in Arcadia Ego,” was a theme that haunted Poussin: even in Arcadia—an ideal land of perpetual summer and an earthly paradise as near to the heavenly one as we are likely to experience—death is present.

Between the head of Poussin/Joseph and that of the Virgin is a large funerary urn, out of which grows a rose bush. This is the “rose without thorns”—the rose as it existed in Eden before the Fall, before the pain of death had entered the world. Its placement here, interrupting the wheel of time, refers to the Virgin's role as the New Eve who redeems the earthly mother of us all. It may also identify her as “the rose of Sharon,” the beloved Bride in the Song of Songs.

Between the head of Poussin/Joseph and that of the Virgin is a large funerary urn, out of which grows a rose bush. This is the “rose without thorns”—the rose as it existed in Eden before the Fall, before the pain of death had entered the world. Its placement here, interrupting the wheel of time, refers to the Virgin's role as the New Eve who redeems the earthly mother of us all. It may also identify her as “the rose of Sharon,” the beloved Bride in the Song of Songs.

Just as the Church sublimated the sensuous poetry of Solomon into the Litanies of the Virgin, calling her “A fountain of gardens, a well of living waters,” Poussin seats her at the edge of a well and casts her here as a Heavenly Venus, a motherly goddess of love and forgiveness to preside over the new Age of Grace.

In the deepest psychological and symbolic terms, her womb and the baptismal basin are equivalent. As the agent of purification and symbolic rebirth, the basin of baptism connects to the role of the Virgin through a famous passage (John 3:3–5), in which Jesus declares, “Except a man be born again, he cannot see the kingdom of God,” and Nicodemus asks, “How can a man be born when he is old? Can he enter the second time into his mother’s womb, and be born?” Jesus answers, “Verily, verily I say unto thee, Except a man be born of water and of the Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God.”

And so, in Poussin’s painting the vessel brought by the boys for the Child’s bath is paralleled by another vessel on the water directly above. This distant boat might seem to allude to the flight from nearby soldiers who would murder innocence. Yet it is not shown ferrying its passenger to the safety of the opposite shore, but instead appears to be making its way upstream, toward the source, as if conveying the soul to its source.

“Consume my heart away”—pleads W.B. Yeats’ aging poet in “Sailing to Byzantium”— “sick with desire / And fastened to a dying animal / It knows not what it is.” Then, like the penitent Poussin, once mortally wounded by Venus and now seeking desire’s quiescence in the embrace of a more transcendent rapture, he prays, “And gather me into the artifice of eternity.”

Poussin used all of his mastery and skill as “faber” to conjure a light-filled artifice of eternity, a world bathed and restored by grace. And he painted himself in.

Responses to “Nicolas Poussin’s “The Holy Family””