My friends and I spent the last months after our high school graduation making memories together before our college paths diverged. We refused to think of the challenges of adulthood that lay threateningly on the horizon but rather spent our time water skiing on Brantley Lake, on the outskirts of Carlsbad, New Mexico, reveling in the few remaining days of our boyhood. The winters of 2009 and 2010 had been excellent snow seasons and along with an unusually wet monsoon season, Brantley Reservoir was swollen almost to full capacity. The reservoir stretched outward from the massive dam that captures the annual snowmelt and flood waters and disperses them among the irrigation canals to inhabitants of Carlsbad like a heart pumping precious lifeblood through an intricate system of arteries.

When the summer ended, I remember pulling onto Highway 285, leaving my hometown behind for the first time and beginning the journey north to Albuquerque and UNM. The lake sparkled blue amidst the dancing mirages of a brutally hot August day, surrounded by the vast brown landscape of the Chihuahua Desert. It was beautiful.

Over the course of the next three years, New Mexico suffered through a period of intense drought. The reservoir shrunk little by little, depleted by the water needs of the farmers and citizens of the local community. As I once again drove out of Carlsbad to begin my senior year at UNM, Lake Brantley appeared out my window as little more than a muddy puddle, so shallow that a person could wade from one side to the other.

In 2013, the situation reached a new low. Water shortages pitted New Mexico against Texas, but also reinvigorated past conflicts among neighboring communities within the state, especially the historic antagonism between Carlsbad and the neighboring cities of Roswell and Artesia. The situation was beyond alarming; it was dire. The state was poised on the brink of a water conflict implying grave consequences for the entire region. Then, in September, a freak series of torrential rains filled the reservoir system to the brim, providing relief to parched farmland and preventing the devastating effects of a legal water war.

Carlsbad is not the only community to benefit from this recent precipitation. Water users farther downstream in Texas will also receive their allotted portion of the newly accumulated reservoir holdings. The unforeseen availability of this water has stabilized the precarious legal situation in the region for the time being. I returned home in mid-October for fall break. As I rounded the final turn and descended through the hills outside of Carlsbad, I was greeted by the sight of the reservoir, full once again and stretching outward from the dam, reflecting the bright blue of the New Mexico sky.

Founded in 1888, the community of Carlsbad grew up along the banks of the Pecos River, a tributary of the Rio Grande. The Pecos provided a steady source of water and along with relatively ample groundwater sources, the surrounding area became a haven for agricultural pursuits. The cities of Roswell and Artesia, located 75 and 36 miles north of Carlsbad, respectively, especially benefited from the availability of groundwater. This water source lies under the surface and is naturally pressurized, allowing easy access for the drilling of wells. When the area was settled in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, local farmers capitalized on this water for irrigation purposes using Artesian wells (from which the city of Artesia received its name).

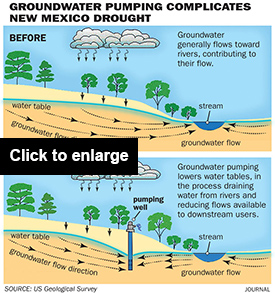

Artesian wells harnessed the natural pressure of the groundwater by simply drilling into the water pockets, resulting in water rising to the surface without artificial pumping. Over time, however, the massive number of such wells in the area began to drain the groundwater levels. This lowered the pressure which had previously been utilized as a natural propellant. Such a reduction in pressure made the use of artificial pumps a necessity for farmers, municipalities, homesteads, and other entities attempting to access the water stored beneath the surface. Further south, Carlsbad farmers did not have access to such an abundance of wells. Rather, they utilized the surface water from the Pecos River.

Artesian wells harnessed the natural pressure of the groundwater by simply drilling into the water pockets, resulting in water rising to the surface without artificial pumping. Over time, however, the massive number of such wells in the area began to drain the groundwater levels. This lowered the pressure which had previously been utilized as a natural propellant. Such a reduction in pressure made the use of artificial pumps a necessity for farmers, municipalities, homesteads, and other entities attempting to access the water stored beneath the surface. Further south, Carlsbad farmers did not have access to such an abundance of wells. Rather, they utilized the surface water from the Pecos River.

In years of plenty, this additional pumping of artesian wells went unnoticed. But periods of drought (which can last from several years to a decade) opposed the needs of farmers in the Roswell and Artesia areas against those of farmers in Carlsbad. This introduced an antagonistic and often controversial dynamic to the already competitive relationship between the two sides, with each faction claiming their rights to water sources. Eventually, these communities formed their own water districts, perpetuating the struggle over access to water. Roswell and Artesia formed the Pecos Valley Artesian Conservancy District (PVACD) while Carlsbad formed its own association, the Carlsbad Irrigation District (CID).

The CID system consists of 25,055 acres of irrigable land, serving more than 600 members whose property size ranges from 1/2 acre residential lots to large farms of over 1,000 acres. The PVACD is over four times larger, serving an area of approximately 110,000 irrigable acres. Not surprisingly, the two districts are quite similar in their crop production. Among the most prevalent crops are pecans, alfalfa, cotton, sorbitol, and an assortment of grains.

While CID members hold the right to receive an annual allotment of 3.697 acre feet per acre of irrigable land from the Pecos River and CID reservoir system, this is a purely theoretical (and optimistic) measurement. In most years, this amount of water is not delivered, leaving farmers to fend for themselves by purchasing other water rights or irrigating fewer acres. Since 1908, the CID has recorded the amount of water received per member. The full allotment of 3.697 acre feet has only been delivered three times in over a century: in 1999, 2005, and 2007. The average annual water allotment received by CID members since 1908 is 2.33 acre feet, about 2/3 the full amount. Unlike the CID, PVACD members have no annual allotment and must rely solely upon the groundwater rights they possess. According to Aron Balok, superintendent of the PVACD, from November 1, 2011 to October 31, 2012 the PVACD diverted (pumped) 378,570.12 acre feet of water from ground water sources. More recent statistics on this year’s water use were not available as of December 4, 2013.

In the most recent (and continuing) drought, these issues have reached new levels of hostility. Because Carlsbad farmers were the first to settle the area and claim water rights, they hold what is called ‘priority’ over the area’s water. Holding priority water rights means that, legally, those individuals may make a priority claim when water is scarce. This claim excludes all other water users until the priority rights holders have received their allotments.

During the current drought, the CID has repeatedly threatened to make a priority call if they were not compensated by the state government for the water they are promised but are not receiving. State Bill 462, which would allocate $2.5M to CID farmers to help alleviate the effects of the drought, was making its way through the Senate Finance and Appropriations Committee when it was tabled. The Committee determined that SB462 needed to be absorbed by House Bill 2, which is devoted to the state budget. The CID claims that the pumping of groundwater by the PVACD has depleted surface water flow, thereby reducing the amount of water in the Pecos river. Charlie Jurva, the president of the CID board, acts as a spokesperson for the members. He recognizes that a priority call is not an appealing solution, but for drought stricken farmers there are few other options.

In this case, the CID holds priority while the PVACD only holds junior water rights. According to New Mexico’s somewhat archaic water laws, which have survived almost entirely unchanged since their creation in the 19th century, a priority call by the CID would effectively force Roswell and Artesia to stop pumping water from their artesian wells in hopes that the excess groundwater would replenish the anemic flow of the Pecos. While this structure of water rights does contain a certain superficial logic, the results would be nothing short of disastrous.

Economically, a priority call would devastate local businesses, causing job loss and crippling personal economies. These effects, claims the PVACD, would not be offset by the CID receiving more water. Also, shutting down the pumps would not result in the CID immediately noticing an increase in surface water, as it can take years for ground water to replenish to the point that water begins to return to tributaries. Essentially, a priority call results in a lose-lose situation for both sides of the water conflict.

Thankfully, just as the CID was beginning the process of making a priority call, Carlsbad was deluged by seasonally uncommon torrential rains. While the rain caused flooding and damage to parts of the city, the downpour resulted in a capture of massive amounts of water in the CID reservoir systems. As of September 11, 2013, the reservoir system contained a mere 14,368 acre feet of water. By September 17, the system held 134,623 acre feet, over 3/4 of its capacity of 176,500 acre feet. In an email correspondence on September 25, Jurva noted that “The threat of a Priority Call has all but disappeared. We still want to work towards rules and regulations to implement a call when it is next needed.”

Obviously, while the urgency of the situation has calmed dramatically, efforts are still focused on a future which is unlikely to include reliable monsoons as Carlsbad saw in September. A good portion of the water captured by the reservoir system will also be used to fulfill water obligations from New Mexico to Texas as prescribed in the Pecos River Compact of 1948. According to Jurva, 17,500 acre feet of water from the September 2013 downpours is reserved for Texas as calculated by the U.S. Geological Service.

In his book entitled High and Dry: The Texas-New Mexico Struggle for the Pecos River, G. Emlen Hall relates the historical development of the region, combining it with his personal experiences working on the legal staff of former State Engineer Steve Reynolds, representing New Mexico in the lawsuit Texas v. New Mexico. These confusing and exasperatingly prolonged legal proceedings arose from contention between the opposing states regarding the water dividends set forth in the 1948 Pecos River Compact.

Hall’s intimate knowledge of the litigation process and the larger-than-life characters who played roles in the water drama helps an average individual understand how the attempt to determine water rights in the arid West is such a problematic and divisive subject. Hall states, “Finally, Texas v. New Mexico taught water managers everywhere that it wasn’t as easy as the Pecos River managers had thought to mix science and politics and law and water.” This predicament is not one of a temporary nature and evokes further uncertainties that loom threateningly on the horizon.

As a native Carlsbadian, I have considered returning to my hometown at some point in my life. However, I am deeply troubled by the possibility that an extended drought could make Carlsbad a ghost town. There are options that could stave off such dire circumstances, including desalinization of brackish aquifer water, or buying water elsewhere and having it delivered. Neither of these are long term solutions, but they could allow time for better solutions to be discovered. The current oil boom the region is experiencing is both a boon and a bane. While the new drilling has caused population growth and a massive influx of capital, which could fund expensive alternatives such as desalinization or the importing of clean water, the industry is an enormous drain on existing water resources.

Before this semester, I was only vaguely aware of the complex, alarming water issues surrounding the entire western half of the country and it appears that the vast majority of local community members are even less informed. Sadly, the common approach to the problem seems to be that of sticking one’s head in the sand and refusing to acknowledge the seriousness of the situation, hoping it will simply go away. While Carlsbad and the surrounding area was pulled back from the brink of disaster in September, the following years my not bear such a fortunate turn of events.

Responses to “New Mexico Water Wars and Their Implications”