The movie “Nebraska” is described as a character-driven road movie. It strikes me as that and something more, a meditation on the decline of the part of America alternatively dismissed as “flyover country” or valorized as “the heartland.” In 50 years, the film may be a favorite of college professors, to be screened alongside Orson Welles’ adaptation of Booth Tarkington’s The Magnificent Ambersons. Both films explore the transformation of America as fueled by the gasoline-powered engine.

In the 1942 film, as in Tarkington’s 1918 novel, a manufacturer of automobiles is asked about the growing pervasiveness of trolleys and automobiles and such,

“So you think they’re going to change the face of the land, do you?”

And the reflective auto maker, played by Joseph Cotton, replies,

“They’re already doing it and they can’t be stopped.”

Later, he adds,

“They are going to alter war and they are going to alter peace. I think men’s minds are going to be changed in subtle ways because of automobiles; just how, I could hardly guess.”

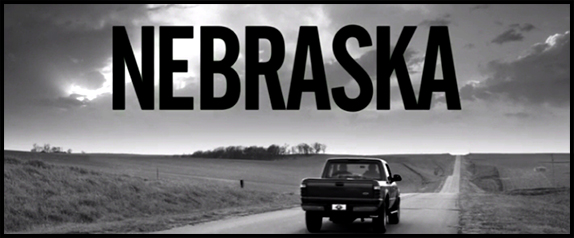

No one speaks eloquently about automobiles in “Nebraska,” but from first frame to last, cars and trucks are central to the characters’ lives and thoughts. In the first scene, an old man is seen trudging along a road teeming with traffic. A highway patrol car pulls up and the officer gets out. Something is clearly amiss. After all, the old man is on foot.

The cantankerous and occasionally delusional Woody Gates is convinced that he has won a million dollars in a Publishers Clearinghouse-type sweepstake. Since he no longer has a driver’s license and doesn’t trust the mails, he repeatedly sets out to walk the 800-plus miles to collect his nonexistent prize. Eventually, one of his sons reluctantly agrees to drive him from Montana to Nebraska, stopping in Woody’s hometown of Hawthorne, Nebraska, for an ad hoc family reunion.

What they pass along the way is a country that emptied-out during the last century, an America of bleak main streets and abandoned farmhouses. Phedon Papamichael’s black and white cinematography captures the beauty of the wintry landscapes, while pitilessly revealing the rundown built environment. If this movie were in color, it wouldn’t be as visually powerful. Color can distract the eye.

The main street of Hawthorne is lined with boarded-up brick buildings, while the residential neighborhoods are filled with once-handsome Victorians covered in ugly siding. The remaining wood porches are all in need of paint. Towns like this, with their supplies and services, began to decline as cars replaced horses. The decline accelerated as towns were bypassed by highways and small family farms were absorbed into larger agricultural units. Distance became a matter more of time than of miles.

It is a land of old people, those who stayed on after their children grew up and left, probably as soon as they had a high school diploma and a tank of gas. The only adults under 50 we meet in Hawthorne are Woody’s fat and larcenous nephews.

Cars are the principal topic of conversation for the males in the family. How long did it take Woody and his son to drive from Billings? What make of car did they drive? What kind of cars does their immediate family drive? What about that 1978 Impala one of Woody’s brother’s owned? No, it was a 1979 Buick.

Woody’s father was a farmer, but Woody was an auto mechanic. What he wants to buy with his riches is a truck, even though he doesn’t have a driver’s license. In the end, his son buys a truck and lets him drive down Hawthorne’s main street. Woody rolls down his window for a better view and instructs his son to duck out of sight. As he drives he sees, and is seen by, an old friend, an old enemy and a lost love. He is a man at the wheel of a large and shiny truck, a man who is autonomous. A man.

Woody drives by his brother Albert, who sits at the curb as he has over the years, watching the cars go by. Except now, there are very few to watch. Once outside of town, Woody and his son trade places in the middle of an empty road and head back north.

“Nebraska” captures both the changes brought about by the automobile and the obsessive attachment that we have had to them. The car—it provides privacy, mobility, status, the pleasures of speed, and much more. It has indeed changed men’s minds as well as the face of the land, all in the space of a mere hundred or so years.

Responses to ““Nebraska:” The Changed Face of the Land”