What does it mean to say we love our children, or that we believe they are our future? What does it mean when our elected officials tell us that education is important, or that the US has the best educational system in the world (a lie we hear frequently, from our president down to the gullible man or woman on the street)?

This isn’t an article heavy on statistics, either local or national. I leave those to the experts. But I will say that United Nations 2012 data lists the United States 17th out of the 21 industrialized countries. Finland, South Korea, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Switzerland, Canada, Ireland, Denmark, Australia, Poland, Germany and Belgium all rank above us in terms of the percentage of national budget devoted to education funding and results obtained. Only Hungary, Slovakia and Russia rank lower.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to tell us why this is. Although we mouth platitudes about the importance of education, although we claim our children are our most important resource, we don’t put our money where our mouth is. We spend infinitely more on military buildup, war, and even our “Second Amendment right to bear arms” than we do on our schools. Our public school teachers are grossly underpaid. Many of our school buildings are urgently in need of repair. President George W. Bush’s obscene No Child Left Behind legislation privileged rote memorization and testing over teaching students how to think, discuss, disagree and exercise their creativity. We continue to suffer the results of that criminal policy.

Year after recent year, New Mexico alternates with Mississippi in ranking 50th out of 50 states in all things educational: the quality of our schools, what our students learn, our ability to keep our young people in school and our percentage of graduates. The New Mexico Mercury and other news sources recently reported Governor Susana Martínez decision to keep class sizes large and privilege uncontrolled development over education.

I am a poet, and as such I do not pretend to be an expert in educational policy or—except in very general terms—what sort of pedagogy has a better chance of producing future generations who will think rather than blindly follow unjust decisions favoring violence over mediation, power plays over negotiation, or the role of world police over being a respectful member of a community of nations.

But I travel widely, and I notice things. It’s easy, for example, to see that there are certain cultures where children are loved, protected and encouraged. Where there is not simply a discourse of respect for the young but a reality that reflects that discourse. Many of the countries where I have been, most of them in fact, are ever so much poorer than ours. Resources are scarce, poverty is endemic, overpopulation presents an ongoing challenge, and problems that would startle us out of our complacency are rampant. And yet, every one of those countries spends more per capita on teaching than we do. Every one designates a much greater percentage of its GDP to education.

Just a few examples. Out of 194 countries, according to UN data for 2009 Sudan designates the highest percentage of its GDP to education, at 27.8 percent. Cuba spends 13.6 percent, Botswana 8.9, Iceland 7.4, Tunisia 7.1, Norway 6.8, and Bolivia 6.3. Of all the countries in the world, Somalia—which doesn’t even have a functional government—is thought to spend the least, at 0.4 percent. The United States is number 55 on the list, with 5.5 percent.

So here we are. The country that glibly considers itself to be the most advanced, the most developed, the most powerful in the world, spends just 5.5 percent of its GDP educating its children. According to UN 2011 statistics, the United States is first in the world in military spending, designating 4.7 percent of its GDP to its armed forces. And, curiously, this doesn’t include what we spend on foreign wars. In our convoluted accounting, that falls under a different category. As always, the “facts” can be made to reflect whatever the speaker wishes.

When I think of education I think of children and when I think of children I think of love. Pure and simple. If we truly love of children, we want the best for them, which surely means giving them the opportunity to grow up healthy, well-educated, and capable of making a more successful stab than we have at designing a better world. Only a real and profound education will provide the next generation and those following the slightest possibility of being able to solve the complex problems with which we’ve burdened them.

As I say, I travel widely. And I’ve been privileged to visit schools in countries much poorer and less developed than ours. In a one-room schoolhouse in a Laotian country village, one determined teacher teaches all the grades. With the help of a very patient translator, I spent a half-day interacting with the students there. I came away convinced they were being taught more thoroughly than in our schools.

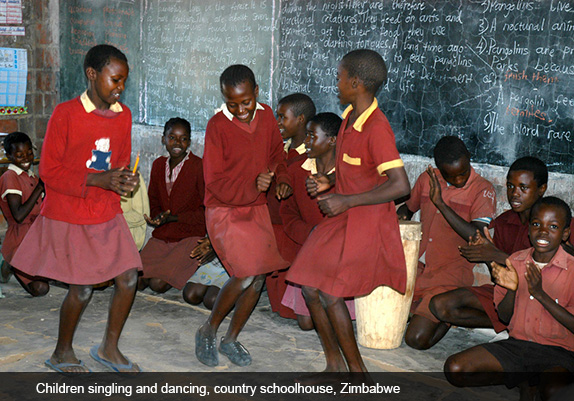

In South Africa I stopped to give a ride to four young girls, walking miles to their school. As we drove through exuberant countryside, our 45-minute conversation showed me that they possessed an excitement I’ve rarely seen among students here. In Zimbabwe a classroom full of girls and boys made music with a joy they carry in their blood and bones. And this despite the fact that their school had no electricity, and the soccer ball we brought them replaced a ball of rags they’d been using to play their favorite sport.

In Yangon, Burma, I visited several monasteries and nunneries where boys and girls from the poorest families are taken in, fed, clothed, and given an education. Many of them would starve, or be forced to sell their bodies, without this important help. I can’t say I was that impressed with the education they were receiving: basic math and reading and writing limited to Buddhist scripture. But I understood that these religious centers were filling an important function. The love showered on the children we saw was evident. They were uniformly radiant.

In much more developed Uruguay, I have followed the One Laptop per Child initiative now applied to every single child from primary through high school. These $100 computers run on solar energy, thus are appropriate for remote regions where electricity isn’t a given. In many farming families, with eight or more children, the fact that each child has her or his own laptop is nothing short of extraordinary. Parents become intrigued and ask their children to teach them to use them too. MIT’s Nicholas Negroponte started the One Laptop per Child program and hoped it would be adopted worldwide. He believed it would give every child an equal opportunity. Yet most countries have preferred not to adopt the program. To date Uruguay is the only country to have fully implemented it.

On Cambodia’s immense Sonle Tap Lake, floating villages are comprised of dozens of shacks, all with simple dugout canoes tied up to little porches, some with floating garden plots as well. The largest and best-cared-for building was the school: a string of freshly painted white classrooms with a narrow open corridor running along the front. I was told that a prerequisite for a child attending school was that he or she be able to swim.

Cuba, since its 1959 revolution, has been fighting an ongoing battle for survival in the face of US aggression. The country has numerous problems, no few of its own making. But Cuban children always come first. Revolutionary Cubans have a saying, "los niños son los mimados de la revolución" (children are the revolution’s spoiled ones), and one sees evidence of this everywhere. Following an extremely successful literacy campaign in 1961, education continues to be prioritized at every level. In a single year, literacy went from 60-76% to 96%. The population now boasts a minimum 9th grade education, and universities and specialized schools have produced generations of doctors, scientists, artists and others.

The children in these and other countries face problems unknown in most parts of the United States. To compare their resources with ours would be absurd. But they all have something we lack: their community and nation’s unwavering love. A culture that arms its military more readily than it educates its children simply does not love them. I can come to no other conclusion.

Responses to “Loving our children means educating them”