“Eleven years ago, I woke up at 2 in the morning, wondering what would happen to unhealthy babies who had no love and who were not as blessed as mine had been. The next morning I felt energized. I was determined to end a cycle and begin research to find out where some of these children were; in sum, I needed answers,” says Patricia Silas, the founder of Los Ojos de Dios, an orphanage in Juárez, Mexico that is dedicated to the most needy of young children.

Patricia and her husband, Gerardo, originally from Puerto Rico followed up with years of careful planning. Working closely with a talented young architect named Felipe Rojas and assisted by companies like Cummins, they built an environmentally sustainable facility that now saves them about $40,000 a year in utility costs and that could serve as a model for construction throughout Mexico as well as in other countries. Some of the questions were – How can we reuse the soil that we’ll be excavating? How thick should the walls be in order to be effective in terms of maintaining a stable temperature in the buildings. How can we site the building to take maximum advantage of the local winds? To quote from their brochure, they have “coupled centuries-old adobe building methods with state-of-the-art wind and solar technologies that can be easily adapted to geography as diverse and distant as that of India and Africa.”

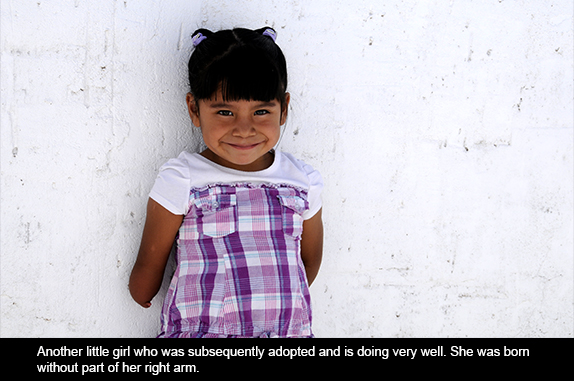

Most of the young patients are Tarahumaras who have suffered from fetal alcohol syndrome and who, in many cases, were abandoned by their families. One example is a tiny girl named Mari Paz who I met two years ago. Because of a virus during her mother’s pregnancy, she was born with only 10% of her brain power. Her family abandoned her when she was 5 days old and miraculously she ended up at Los Ojos de Dios. When she started having seizures, however, the local hospital wouldn’t treat her because she was an orphan and had no family or papers. By chance, however, then-President Felipe Calderón came to Juárez to promote a new healthcare plan that he claimed would cover all Mexicans. Patricia challenged him, pointing out that orphans – there may be more than 1 million in Mexico – had been left out, referring to the experience of Mari Paz. Calderón then amended his plan, based on Patricia’s comments and Mari Paz’s situation.

Patricia has said that, “Every life has a purpose,” even the life of this tiny, badly damaged little girl whose story helped change the law to benefit all orphans in Mexico.

There are now 35 children in the program, including three who arrived on October 3, Carmelita, Diana and Emanuel. “This is hard work,” I say to the nurse who is watching these three newly arrived orphans. “Hard but beautiful,” she answers.

Now Patricia and Gerardo have taken a new step; the inauguration of a Centro Comunitario de Rehabilitación that will provide various types of therapy to some 144 people in the first year. This will be for people who have no employment or insufficient funds for private therapy. Often these people are the victims of the violence that has ravaged Juárez. One example is a boy named Kevin who was born with a disability. His parents were killed in a shooting and he lives with his grandfather who makes 50 pesos a day as a parking lot attendant. There are simply no governmental services for someone like Kevin and, as in so many cases, private citizens like Patricia and Gerard are filling the gap.

There are other gaps as well. For example, Los Ojos de Dios has a small hospital within its main facility. Why? Because it is so difficult to get a child to a hospital should there be an emergency. They have no ambulance and calling for a public ambulance is an exercise in futility. “What happens when you call in an emergency?” I asked. “Nothing. No one comes,” was the answer.

Their facility is located in an industrial park near the airport. Recent heaving rains washed out part of the road. City officials have come in and excavated a dirt roadway to connect the facility to the main road but no one knows when a permanent paved replacement will be installed.

What draws me back to Juárez month after month is the opportunity to work with people like Patricia and Gerardo and the many others like them who have filled in for the lack of the kind of social services that we have always taken for granted here. This includes other orphanages, food banks, rehab centers for young women, house building projects and even a privately funded mental asylum. Despite the violence that too often dominates the headlines, there is a level of humanity here that I have rarely experienced anywhere.

Responses to “Los Ojos de Dios”