For Carolyn Kinsman and for me, the process of moving to a foreign country had been a slow one. We first encountered Kino Bay near the end of a long road trip that began by heading south through the heart of Mexico via Chihuahua, Torreon, Aguascalientes – all old favorites of mine from earlier backpack-and-bus-ticket days, back when you really could visit the country on $5 and $10 a day. I had wanted to experience the unsullied core of the country and avoided the Gringo playgrounds along the west coast. But this time we returned up the Pacific side by way of Guadalajara, San Blas (sweet place to get 'San Blasted'), Mazatlán, and San Carlos/Guaymas where we camped out on the beach near where they filmed Catch 22. It was all new to me. I had read of little Bahia de Kino in PA (Progressive Architecture Magazine) in an article featuring a dramatic condo project and a spaceship-like beach house. I was intrigued.

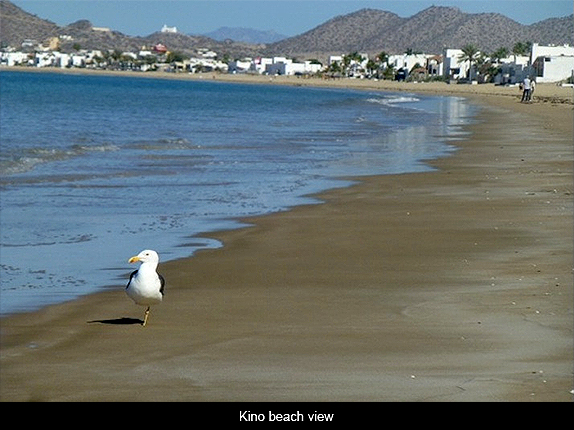

As we topped that final large dune leading to New Kino we saw an immensely beautiful curving beach sweeping away toward distant Tiburón Island, and were smitten. I had eaten an unwashed orange on the beach the day before while in San Carlos and spent much of my first visit to Kino Bay hugging the porcelain throne. But the 'Jacquelynn' condos were there, and the frolicsome 'spaceship house,' built by Marcel and Barb Sedletsky, looked onto nearby Isla Pelícano. Kino was a beautiful place; we vowed to skip the long road trip theme for our next getaway and just head back to Kino Bay for some serious relaxation. After that it didn't take long to get to the "Do you think we could live here?" discussion. At that time we had no money to speak of, so much of our talk was irrelevant. But over several yearly visits of 'due diligence' by hanging out in the water as the sun was setting, we ran through the pros and cons. Our results: lots of pros; few cons.

There's no heavy industrial base located directly on the Sea of Cortez. There are only a few large cities (Guaymas and La Paz) that might dump pollution into the Sea, and they're sufficiently distant from Kino to mitigate most problems. There are large agricultural fields, pecan orchards and table grape vineyards starting about 10 miles inland and producing crops for the US market, but there are none hugging the shoreline and producing nasty run-off. The worst of it was the overfishing that plagues this beautiful body of water that Steinbeck extolled in The Pearl, and The Log of the Sea of Cortez. If we had been standing on the beach at Bahia de Kino in March of 1941, around 8 months before The Big War began, we'd have seen that trawler carrying Steinbeck and Doc Ricketts as they chugged along the horizon offshore heading south from Tiburón Island toward Guaymas. This Sea is a special place that Jacques Cousteau called the "world's aquarium" and the "Galapagos of North America." The overfishing was a disappointment; and, as foreigners, there wasn't much we could do about it; but it was not hard to imagine ourselves living here.

Yet retirement was a new concept for us, a new life skill to be learned. There were lots of scary tales in magazines and online that warned of the pitfalls, but mostly wanted to sell us various products. We decided to do it our own way. For the first couple of years we wrote down every single peso we spent and tallied it up at the end of each month. We abandoned that system after finally realizing the horror stories of people blowing quickly through their money just didn't apply to us. Although we enjoy a 'sundowner' most evenings and decent wine with dinner (yes, there are some very good Mexican wines these days), we're not heavy drinkers or lavish spenders. We're happy with our older reliable car, and gambling in Las Vegas holds no appeal for either of us. If anything, we were both a little afraid to spend money. It was a good exercise, nonetheless.

In fact, we soon realized that moving to Mexico gave us a big raise, as our cost of living dropped markedly. We managed to buy an old wreck of a house on the beach and completely re-imagined it with money from selling our place in Albuquerque. The views, of distant islands and headlands on the Baja, and the occasional pod of dolphins, needed little improvement. Since this would be our new home and we'd potentially be living here year-round, we invested well in insulation. Now we're more comfortable than many of our friends and have lower bills. We, along with many others here, live quite well on our Social Security alone. We use our retirement income for travel, with no need to cash in what pitiful amount is left in our IRAs after the Wall Street Bankster Looting we all experienced recently.

As a side benefit, when you start a major construction project in much of Mexico, 10 'Spanish teachers' show up at your door every morning for the next several months. Not one of our crew spoke English, and really why should they? It pushed me to finally get my Spanish up to a decent level. If you want a project to turn out reasonably well, you'd be advised to learn enough Spanish to deal with the daily issues that appear. And in our travels we've found that Spanish is the world's second most useful language, after English. They say that, "A person with two languages lives two lives." It can be one of the richest gifts to bestow upon yourself.

While Spanish opens doors throughout all of Latin America, of course, outside of Spain and northern Morocco, few Europeans seem to speak it. Yet even that fact was surprisingly useful this last summer when we boarded the midnight train out of Belgrade, bound for Sofia, Bulgaria. We shared a rail car with four other people, several of them very rough-looking Serbs. We weren't entirely sure how badly the recent wars had affected most people in the Balkans, so as the night progressed we found our Spanish very useful for private conversations. A German lady looked up in surprise at two Gringos speaking Spanish; she told us later she'd been so sure we were Americans. We later spoke to some of the other passengers and were told by a nice Serbian fireman there are so many different languages in Europe that it's impossible for most people to learn them all – or even most of them. So English has become the lingua franca for Europe as in much of the world. Our Serbian friend continued, "We learned English in school so we can talk to other Europeans. But we have our own 'English' because we rarely talk to native speakers." He was apologetic for his improvised English, yet we assured him we wished we spoke any of many European languages that well.

Despite what some people want to believe, it's still very possible to live well on a modest budget south of the border, unless you need imported (i.e., US) goods, or own a gas-guzzling power boat and big truck. It's cheap to catch fish at a local restaurant, deliciously prepared and served on a plate, with a cold margarita standing proud beside it. And traveling for several weeks at a time on Mexico's fine long-distance bus system can be very reasonable way to explore the rich culture of the southern areas. It can also be much cheaper to catch an AeroMexico or Volaris flight out of Hermosillo to Mexico City, Mérida, Guadalajara, or Oaxaca than flying in from San Diego or Albuquerque, for example. Crossing the border by air can be costly.

A recent article in The Atlantic Magazine (July/August 2013) pointed out that "a senior in the 40th income percentile in the US would be in the 90th percentile in Mexico." I haven't bothered to check our standing on the US percentile scale (what's the point?) but we, and others, live nicely above our pay grade south of the border. The same article noted that life expectancy in the US and Mexico is essentially the same, but the annual cost of healthcare is about 8 1/2 times more in the US for the same outcome. (It's about 6.8 times more expensive in the US than in Costa Rica or Chile, where lifespans are also similar.)

A medical emergency can hit any of us at any time. Despite our healthy lifestyle, Carolyn had a recent bout with pneumonia that put her into the hospital for two days. Yet our total bill at the fine modern CIMA Hospital in Hermosillo, including a private room (all the rooms are private), prescriptions, X-rays, a CT scan (about US$500), and excellent care from our well-educated Mexican Doctor came to around US$3000. That's a chunk of money for us, but we may get some of it back from our US insurance. If not, we can still afford medical care here. That's what savings are for. And when we call for an appointment, it's often the doctor who answers the phone and makes the arrangements. In addition to our primary care doctor, we've also found a good dermatologist, an orthopedist, a dentist, and an ophthalmologist. In fact, we have the cell phone numbers of several of our doctors. Care is personal here.

In an amusing cultural aside, the lady at the admitting desk was scandalized when I mentioned I would not be sleeping on the couch beside Carolyn's hospital bed for the two days she'd be on an IV drip, but would be at home an hour away. Here in Mexico, the family expects to stay with a sick relative and brings their own blankets for sleeping over. But Carolyn was knocked out by the meds, and staying there seemed pointless to a heartless old Gringo like me.

Most retirees here are very active. And the Sea is wonderfully warm for swimming about 6 months out of the year. There's a funky but friendly 'retiree club' in an old quonset hut in Kino Bay with an array of activities ranging from charitable activities to walking aerobics and weight training to bocce and bridge. There are Saturday night dinners and Sunday breakfasts on alternating weekends, Social Hour every Friday night, and a well-stocked library. Membership is not restricted to Gringos, but only a few of our Mexican friends find old Gringos interesting enough to join us. On weekdays there's little traffic in Kino, so it's easy to ride a bike. There's a real desert golf course (guaranteed no grass!); it's not for pampered city folk, and it's heavily enjoyed. It's easy to walk to a good restaurant, hike out to nearby mountains, walk your dog on the beach as the sun comes up, or enjoy a cold drink as it sets.

There's so much more to tell, but that awaits another day….

Responses to “Letter from México: Part 1”