Project Statement: Catolicismo

The del agua in “San Felipe del Agua” refers to the fact that a portion of the water from which the colonial Mexican city of Oaxaca lives, flows down from the gem green hills behind what was once a town but now exists as the edge of the larger city: lambs, donkeys, tropical flowers, and a half-hour bus ride to the center of a cosmopolitan metropolis. Those born in San Felipe have a separate set of rights and responsibilities to the community than those who move here. Those who move here tend to bring wealth, and often live behind high walls and drive dark-tinted SUVs.

My family and I lived in Mexico for one year and chose San Felipe because we found a wonderful school there for our children. Having grown up in New Mexico I have always been attracted to Catholic imagery and Guadalupe, growing up atheist I have always been fascinated by faith. And so, in Mexico, I photographed our neighborhood parish.

The photo essays resulting from this study will be published in the New Mexico Mercury from October 2014 through June 2015, roughly once a month on the date corresponding to the event photographed one year previous.

La Aurora de la Virgen del Rosario

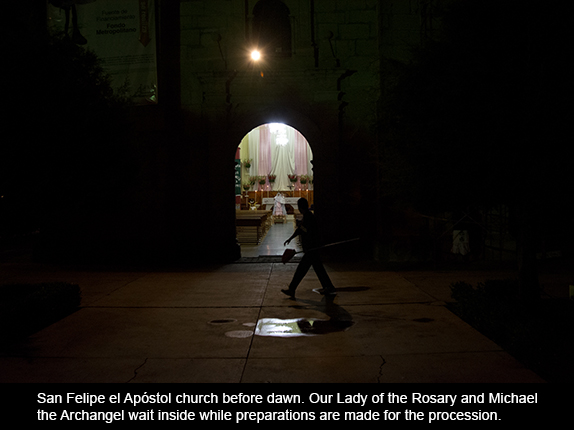

It was not yet five a.m. when the first exploding cohetes and clanging church bells insisted I be there already. I hurried through black and silent streets, but when I arrived I was informed that I should wait inside the church until the procession was ready to begin. Only one other family—of three women—waited in the pews. Soon I rose to photograph the Virgin (Our Lady of the Rosary) and Archangel, placed in the church crossing in preparation to be carried through the neighborhood. I took pictures of Mary with her baby and had turned toward St. Michael when an older man brusquely ordered me not to take close-ups of the idols. So I sat back down. The musicians arrived, boisterous, and formed a semicircle in the churchyard; they blew their horns to fill the empty nave.

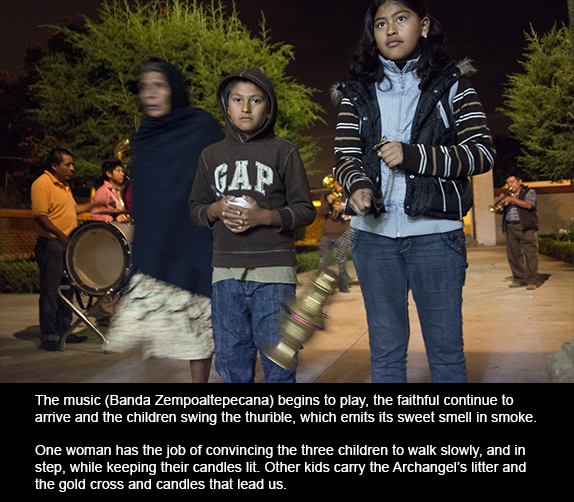

Forty-five minutes later the space was full of sleepy families, hands fluttering silent in the sign of the cross, identical each to the other and to those who had taught them as children, as they filed into the pews to pray with or to the Virgin. I suppose it was mostly women, as per the stereotype: older, alone, heads covered by rebozos, strong legs belying wrinkled faces. But lots of families, with papas, and kids who had been roused from bed on this autumnal Sunday morning. (As it turned out, most of the children took official roles in the procession.) Some devotees went directly to the Virgin and knelt before her; three women offered her bouquets exploding from baskets, which they brought atop their heads and which would join us in the procession.

In the context of Mexican culture, where the most common epithets contain the word “mother” yet Guadalupe is the primary spiritual touchstone, the trichotomy of mother/virgin/whore is ever present. This is further complicated when one reflects upon the faith as expressed here: the frozen icons like children’s dolls, all dressed up, their garb an oversized triangle (albeit often painstakingly embroidered) falling from the face, a crown or headdress heavy over the head: unfairly—it seems to me—denying the body, even in its very embodiment.

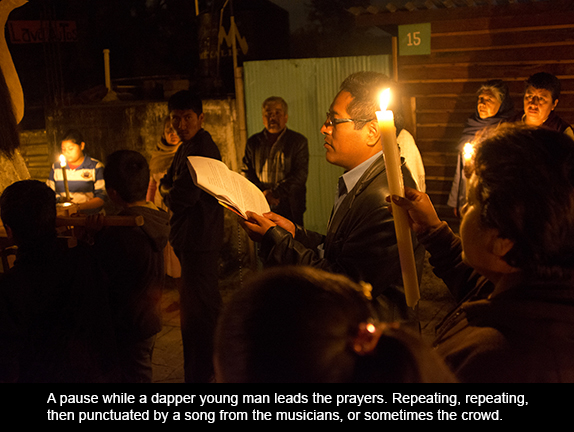

Our light consisted of the glow from oversized candles. Four young women elegant and beautiful—black hair, dresses white, with traditional embroidery, and rebozos draped—balanced the Virgin’s litter on their shoulders. Our passage seemed a sweet call to the sleepers behind walls: música alegre, rhythmic intonations and quiet prayers; the glowing gown of the figure hoisted above the crowd; and the details of relationship—daughters holding mothers’ arms, fathers holding sons’ hands, no one walking in front of the Virgin.

“Viva Maria

Viva Rosario

Viva Santo Domingo”

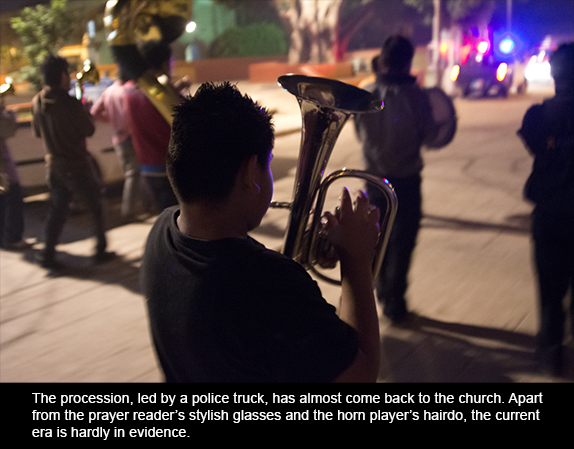

We walked the undulating road of rounded stones between the darkened, high walls of the rich, who have recently come to stay: in this moment the timeless ritual ruled. It suddenly made sense that we do this before dawn. We had the street; the shiny SUVs that choke it, the aggressive buses, the shoppers and the shops were asleep. Those elements of the street that typically consumed my attention—the posted bills, ubiquitous dog poop, uneven sidewalks, the fancy address tiles, the quaint colors—were all blended into darkness and periphery.

When we had come full circle, the pews were carried out to line the walkways of the churchyard. Tea, Mexican hot chocolate, pan dulce and tamales were handed out. People awkwardly sat next to strangers (at least that’s how it felt to me) and were awkwardly watched as they maneuvered these messy gifts to their mouths. Finally the band struck back up, jovial as ever, and people started carrying their breakfasts home, to share with loved ones or at least eat at a table. The sky was light now and the Virgin and saint safely ensconced again in the satin-draped church after their turn through the barrio.

Responses to “La Aurora de la Virgen del Rosario”