Within the tempestuous teacup of Santa Fe’s summer art season, it could be easy to miss a rare mini-retrospective of work by Dana Newmann, one of New Mexico’s cultural treasures.

The show opened on July 11 at the beginning of the touted “Trifecta” of art events that included the International Folk Art Market and the Art Santa Fe art fair, which debuted the same night, and SITE Santa Fe’s revamped biennial, “Unsettled Landscapes,” unveiled on July 17. But besides the crowded calendar, there’s the matter of the show’s out-of-the-way location. It’s been mounted at Phil Space at 1410 Second Street (where it will run through August 8)—far from the trendy Railyard District and the historic Plaza, and a safe distance from the faded charms of Canyon Road, now invaded by parasites and burned-out by its strained efforts to be a flame for the tourist moth.

Located in a nondescript storefront complex, Phil Space is operated by artist/photographer James Hart as a kind of alternative exhibition space adjacent to his photography studio. Although it got underway informally around 2000, it began to make an impact in 2009 with a show of local legend Jerry West. In any case, it is one of the few place in Santa Fe nowadays where you can still get a sense of the wonderfully gritty, independent spontaneity that once characterized Santa Fe’s contemporary art scene in the 1970s.

Dana Newmann arrived in Santa Fe with her husband, painter Eugene Newmann, in 1972, answering a call from the state’s department of education. For many years she made her living as a teacher and has even authored books on early childhood learning. But she trained as an artist at the California College of Arts and Crafts, a venerable Bay Area art school that was founded in 1906 as an outgrowth of the interdisciplinary aesthetics of the Arts and Crafts Movement. She had Richard Diebenkorn as her drawing instructor and studied painting with the Italian abstractionist Afro Basaldella. Settling into a rented house on upper Cerro Gordo Road, she and Gene were content to quietly pursue their own highly individualistic work. But they soon found themselves caught up in the rough-edged and developing community of artists that by the mid 1970s began to shake Santa Fe awake from its long slumber.

Last spring, the present-day Center for Contemporary Arts in Santa Fe made a botched attempt to pay tribute to the spirit of the artist-initiated “Armory Shows” of 1977 and ’78. Held in the old WPA armory building, the original shows were a grass-roots (and grossly uneven) effort to give exposure to the broad range of new art being produced in Santa Fe at the time, much like the famed Armory Show of 1913 in New York, which gave America its first introduction to modern art. Both of the Newmanns participated in those Armory Shows of the seventies—as did Andrew Dasburg, who, at 90 years of age, was the dean of modern art in New Mexico at the time and the last surviving exhibitor in the 1913 Armory Show. (Although the CCA blew its chance to capture the spirit of the 1970s, you can still catch a glimpse of it in a little show of work by John Connell at the Harwood Museum in Taos over the summer, which includes a couple of large-scale paintings by Gene Newmann made as part of a collaboration.)

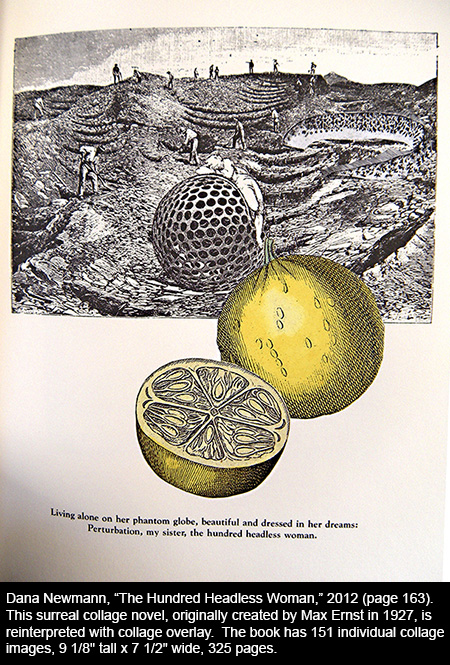

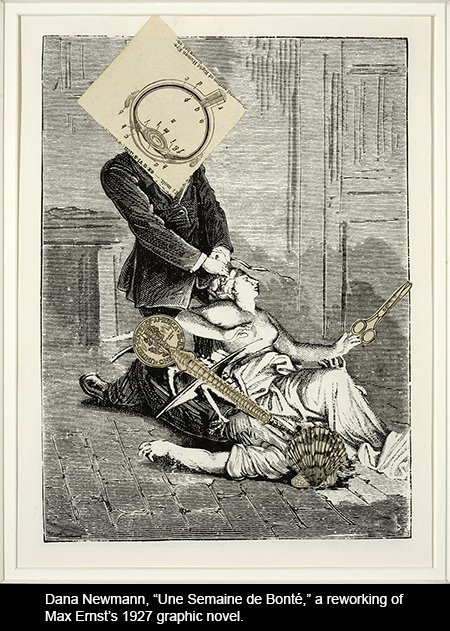

Dana (pronounced like “Dan” and not like “Dane”) has chosen to call her 45-year retrospective “In the Realm of Surrealism,” acknowledging the importance of the 1920s movement to her evolving aesthetic. She is showing thirty pieces, including collages, three-dimensional assemblages, some small bronzes, three “cabinets of curiosity,” and several examples of book art—including a complete reworking of Max Ernst’s 1927 graphic collage novel, The Hundred Headless Woman.

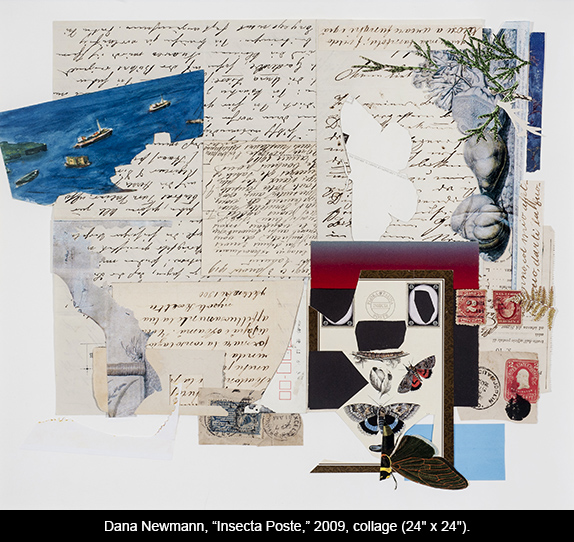

At the basis of these works is a kind of search and rescue mission. She retrieves the discards and surviving fragments of the past, taking up bits of chance occurrence and finding new possibilities of order when they are brought together.

One elemental impetus of art making is a desire to give some sort of permanence to fleeting reality. So whether or not they make “pictures” in the usual sense, artists are often compulsive collectors, snatching what they will from the stream of time and taking it back to the studio as a talisman and muse. In her introduction to New Mexico Artists at Work, a book featuring local artists in their studios, which she authored in collaboration with photographer Jack Parsons in 2005, Newmann comments on the personal collecting habits of artists:

Accumulating and displaying things by category, or by some other associative order, seems to be fatefully appealing to artists; most collect something, whether it be brushes or art books—or just positive reviews of their work. Although the tastes and sensibilities of today’s artists differ from those of a traditional collector like Blumenschein, many of them nonetheless have displays and arrangements in their studios through which they proclaim their sense of what counts. Some artists thrill to the formal perfection they discover in nature or even in humble man-made objects not traditionally valued as beautiful. Others respond to the metaphoric or subconscious resonance in a cast-off glove or a weathered metal sign. With age certain objects acquire a patina, the iridescence of time or decay; the act of retrieval and display celebrate a kind of heroic promise of resilience and transformation. Perhaps these impulses have a special poignancy here in New Mexico where erosion of land and culture is always threatened.

Newmann is an inveterate collector herself, and the impulses she describes underlie her own activities. She seems to seek both “formal perfection” and “metaphoric or subconscious resonance” in her flea-market finds and in her arrangements. Her attic-like studio on the second floor of the house they built in the 1980s in rural Ribera is indeed like a farmhouse attic—chock full of miscellaneous retired discards and mementoes from the past that no one really has the heart to part with, kept for hopeful redeployment.

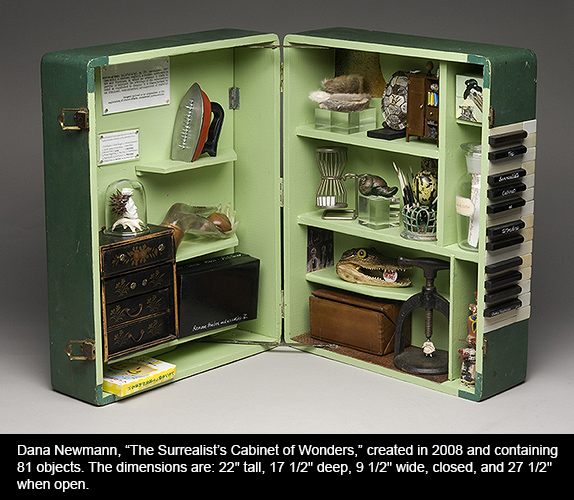

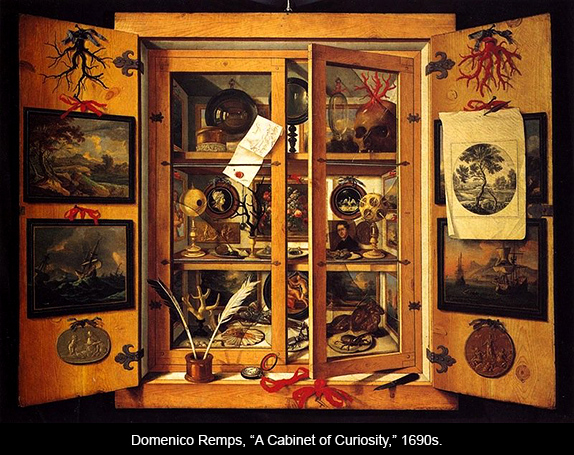

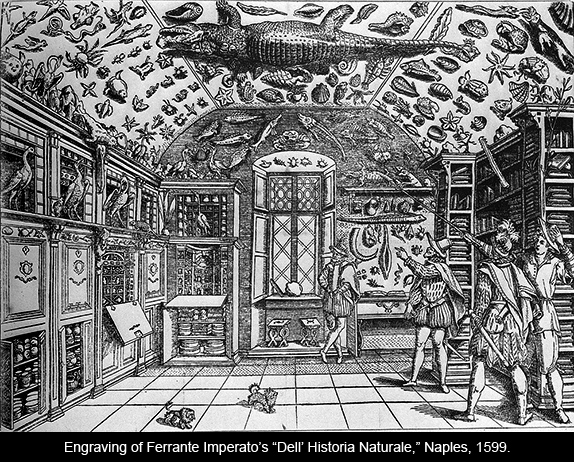

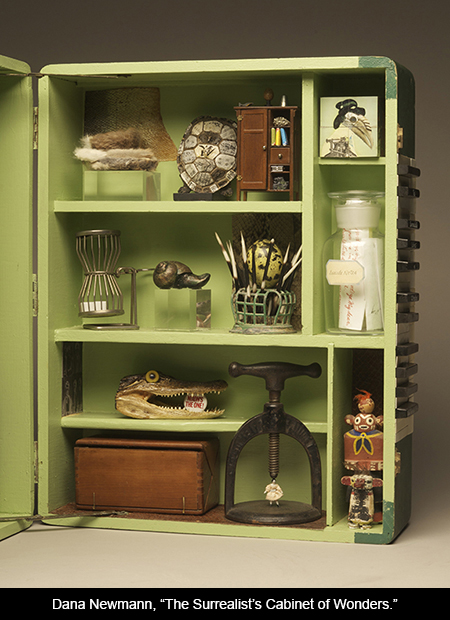

A signature work in the Phil Space show is “The Surrealist’s Cabinet of Wonders” from 2008. Newmann has made several boxes of this sort over the years, inspired by old-time “Wunderkammer” or “Cabinets of Curiosities.” Such “cabinets,” or “chambers,” were eclectic collections of natural wonders and human artifacts that aristocrats and antiquarians began to assemble in the sixteenth century and they are precursors of our museums.

In this particular case, she was also inspired by Marcel Duchamp’s “Boite en valise” or “Green Box,” a traveler’s suitcase filled with miniature replicas of his “readymades” and other art works. Duchamp’s “valise” was both an idea for an edition and a portable museum summarizing his career, produced for a quick getaway as he was preparing to leave Occupied France in 1941.

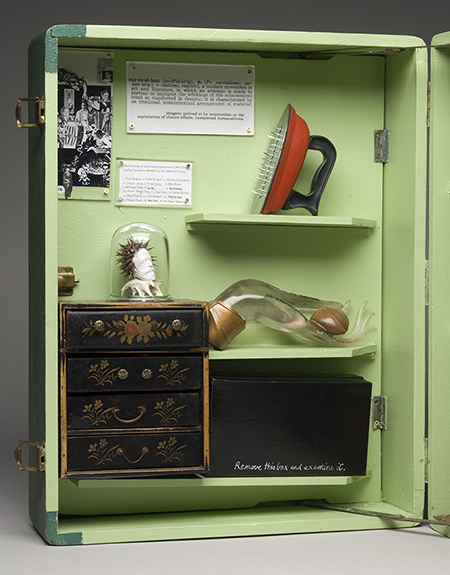

With keys of a musical instrument fixed on the outside, Newmann’s “Cabinet” is like a cross between a traveling salesman’s sample kit and something a mountebank might employ to drum up a crowd for his snake oil and magic show. Using dollhouse furniture and toy household objects, Newmann pays homage to her Surrealist forefathers and godmothers, making miniature replicas of their famous pieces. She replicates Man Ray’s “Cadeau” (“gift”) as a toy clothes iron with a line of tacks; and a child’s tea set, wrapped in fur, reproduces Meret Oppenheim’s notorious “fur-lined teacup.” A dice cage with two white cubes recalls Duchamp’s “Why Not Sneeze?” and a couple of kachina dolls are a reminder that Max Ernst and Andre Breton and the other Surrealists collected them.

But with gleefully disturbing wit and humor she adds to the suitcase a slew of items of her own devising. A steel vice bears down on a tiny doll in a hoop skirt. A stuffed baby caiman’s head clenches a “Nixon’s the One” button in its jaws. An elegant glass hand holds a netsuke beetle and bears an inscription: “A peach in the hand is worth more on the tree.” There’s a pharmacy bottle containing suicide notes. And under a glass bell jar (that mainstay for keepsakes in Victorian parlors) we find a plaster bust of Tchaikovsky. The composer of the “Nutcracker” and the “Pathetique” symphony is honored here as a monarch of the imagination, balanced on the skull-bones of a couple of tiny ferrets and wearing a fairy’s crown that resembles a chestnut hull.

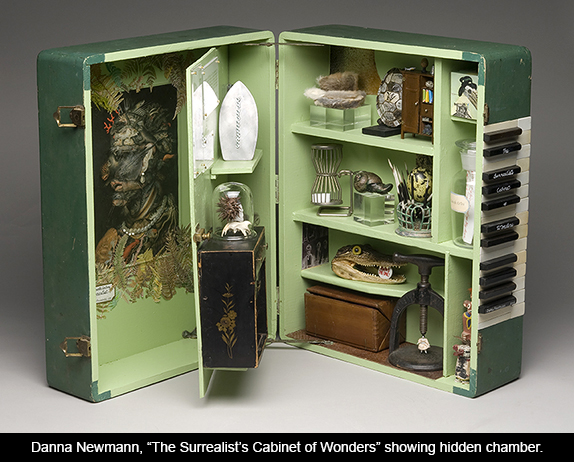

Deepening the layers of reference, Newmann outfitted the suitcase with a false bottom. When opened, it reveals a fantastical image by one of the deep ancestors of the Surrealists. It’s a painting of a human head composed entirely of sea creatures by the sixteenth-century Mannerist artist Giuseppe Arcimbaldo, which she has lovingly decked with pressed ferns.

You could say there’s nothing new here; and in a way that’s part of Newmann’s intent. In all of her work she re-uses old materials and old techniques. But she brings to them a subtle wit and intelligence. She revisits art movements of the past—Surrealism, Cubism—because she finds continued vitality in their discoveries. Everything is old; and everything is open for renewal. “The nice thing about the past is that it hangs around until you’re good and ready for it.” (This line is from one of the cut-out quotes that she has collected and pasted into a collage album that she calls a “Segue” book.)

The original Surrealists used collage for its potential to produce shock. Influenced by the theories of Freud, they brought together disparate elements into unnerving juxtapositions that cannot be dealt with by the mind in a rational way. Shock, they believed, by-passes the conscious mind and goes directly to the subconscious. They wanted to stimulate the subconscious mind and trigger new associations in a manner similar to dream processing.

“A work cannot be considered surrealist unless the artist strains to reach the total psychological scope of which consciousness is only a small part,” wrote Andre Breton (Surrealism and Painting, 1927). “Freud has shown that there prevails at this ‘unfathomable’ depth a total absence of contradiction, a new mobility of the emotional blocks caused by repression, a timelessness and a substitution of psychic reality for external reality, all subject to the principle of pleasure alone.”

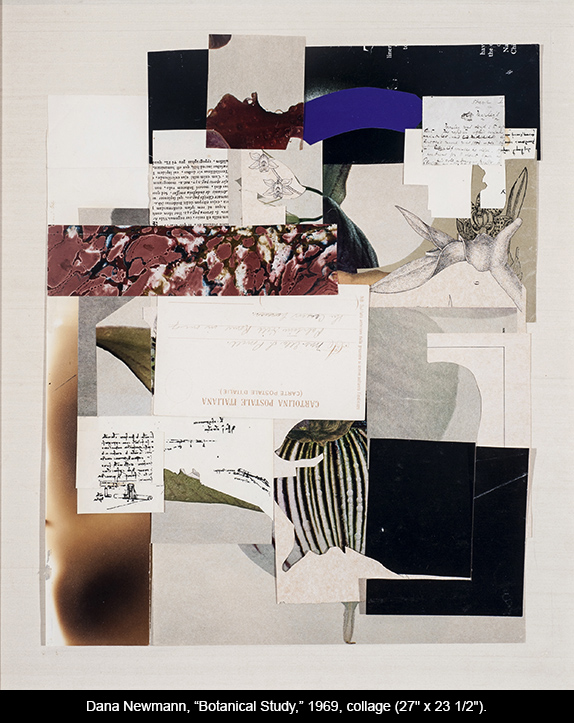

The earliest collage in the show, “Botanical Study,” dates from 1969, while Newmann was still living in California. At the time she and Gene were house-sitting for a friend out on the Monterrey Penninsula. The house jutted out over the ocean and had glass blocks built into the floor so that you could see the water coming in underneath. One of her tasks was to take care of the numerous orchid plants scattered throughout the house. There, in that strange suspension over the tides, she undertook a collage on the theme of orchids.

The work is a masterpiece of unexpected juxtapositions and subtle integration, using orchid illustrations from old botany books and magazine photos of plants; a bit of marbleized endpaper; a fragment from Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks; some hand-written notes for what appears to be a school report on Dickens’s “A Christmas Carol”; and a yellowed post card addressed to “Mrs. Ella S. Powell,” informing her that the unseen side represents “Palatine Hill in one of the Ceaser’s [sic] houses” (with much uncertainty about how to spell “Caesar’s” and ignoring the directive, in Italian, that that space should only be used for the address). At the top there is an arc of pure purple, a reminder that “orchid” is also the name of a color.

In the upper right, Newmann has skillfully grafted the stem of another plant onto the inner petals of an illustrated orchid. Cutting out shapes and then deftly reusing the leftover scraps to create subtle echoes here and there, she produces a kind of visual chamber music, an intricate interlocking unity with delicate rhyming harmonies among its parts. Though chance plays a role in the encounter among the components, she has an unerring eye for finding harmonies among the pieces that chance has brought together, tying them into a satisfying visual unity.

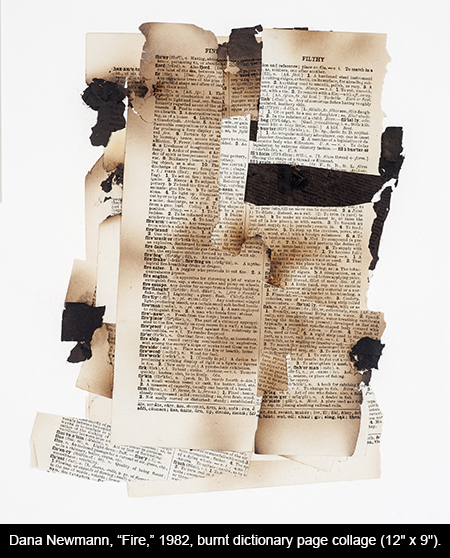

“Fire,” from 1982, occurred by chance. Newmann was cutting out illustrations from an old dictionary and tossing the leftover pages into an open fireplace, where, inadvertently, coals still smoldered. She retrieved the page scraps just in time. Appreciating the serendipity of how the dictionary column was dominated by “fire” words, while the headings ranged from “fine” to “filthy,” she basically used the charred pages as is.

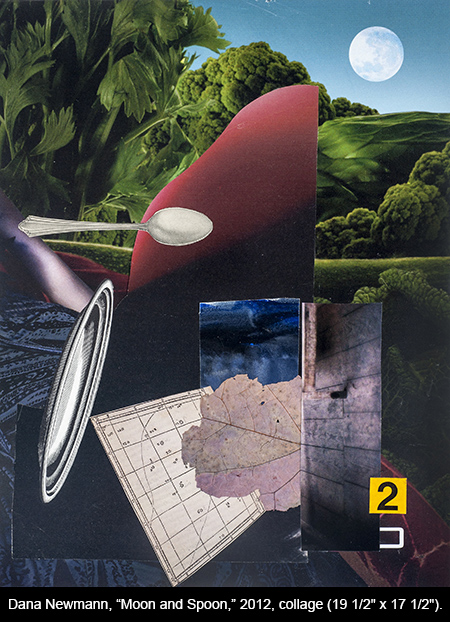

“Moon and Spoon” (2012) suggests the corny romance of a midsummer night’s picnic. We see the moon rising, and nearby, the dish and the spoon that ran away together—although it now seems they may have had a falling out. But nowhere is the cow that jumped over to be found, unless it’s now the juicy red steak in the lower right. The green landscape under the moon is actually made up of edible vegetables. Broccoli and celery leaves serve as trees and kale becomes a shrub. In three harmonious tones, the round moon and the two ovals of the spoon and dish initiate a rhythmic effect, held in place by the curves of a dark red blanket that is quickly shrouded in nighttime shadow. But see how the edge of shadow joins the shadow in the green leafy field of the landscape? And how the delicate lines on a star chart (seen in perspective) link up with the more irregular veins of a pressed leaf, which in turn join to the linear cracks between floorboards in a neighboring photograph (also in perspective; and on its side), and then find an echo in the marbling of the red meat and the veins of the nearby green kale? All of this produces a linear network of interlinked spaces and a rhythmic dialogue between depth and flatness, straight and crooked.

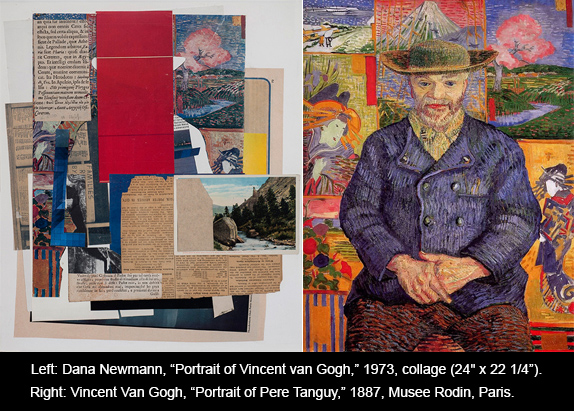

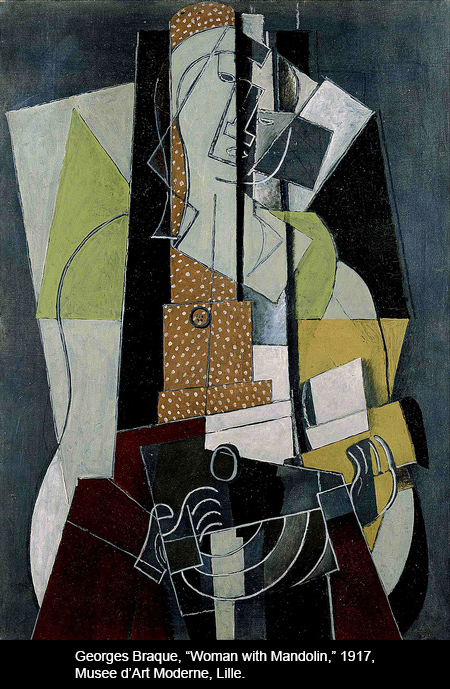

Newmann’s 1973 “Portrait of Vincent Van Gogh” is basically a reworking of Van Gogh’s 1887 “Portrait of Pere Tanguy.” She has carefully cut out the figure of Tanguy, leaving only a partial silhouette and the miscellaneous Japanese prints that originally formed the portrait’s background, tacked to the wall of Tanguy’s shop like a proto-collage. She replaced the figure of Tanguy with a red rectangle, which she has coordinated with a smaller yellow rectangle and bits of blue to anchor the composition in primary colors. Close inspection reveals the red rectangle to be Barnett Newman’s “Vir Heroicus Sublimis,” turned on end. The white “zip” line in the heroic 1951 painting cuts across its surface at the exact point where the brim of Tanguy’s hat was originally located, remnants of which can be glimpsed on either side. With its flat planes of collaged papers and multiple punning references (like the homonymic artist’s name), the piece pays direct homage to the sophisticated Cubist portraits of 1912 – 17, which were in turn full of insider jokes and witty references to the tradition of portrait painting.

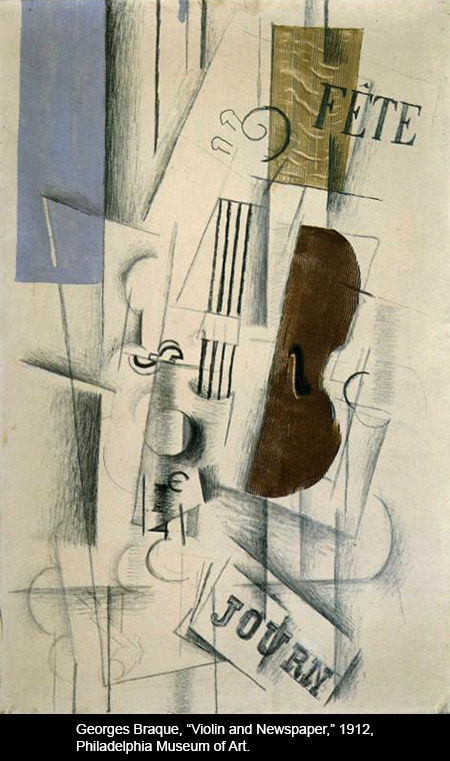

Collage was invented by the Cubists in the early 20th century. It emerged as an aspect of their exploration of visual synecdoche, in which a piece of wood-grained wallpaper would be pasted onto the canvas to suggest the entire texture and material of a guitar or tabletop. The new art that came to be called Cubism was an effort on the part of Picasso and Braque to come up with a new language of visual representation. They reasoned that all painted representations were basically meant to place the subject before the mind of the beholder, but that painters had traditionally presented the subject only in a simple view, frozen in time like that of a camera. What the Cubists wanted was to evoke the subject in the viewer’s mind in a richer and more conceptual way.

For the Cubists, the daily newspaper became the model of how reality is experienced in modern life, and they used lots of strips of newsprint in their collages. With the speed of developing electronic communications behind it, the daily newspaper brought the world to the breakfast table, a reality that the reader had to piece together out of fragments collected on the page. In like manner, the Cubists sought to stimulate the viewer’s imagination and to provoke the viewer’s mind into a more active participation. They felt that by supplying only an artful arrangement of visual cues, the viewer would become actively involved, and the experience of the painting would more closely approximate the way we actually experience the things of reality in our minds.

It was the Cubists’ way of provoking the mind into participating that appealed to the Surrealists. With their irrational juxtapositions, the Surrealists simply wanted to strike a deeper psychological chord. And by gathering together fragments of a lost reality—each of which carries with it the patina of a quite specific (though largely unknowable) history—Dana Newmann provokes a similar participation on the part of the viewer. Everything seems tangible, but just out of reach.

A new collage from 2014 is titled “James Joyce Contemplating the Natural World.” Joyce was not a Surrealist, but his writing operated in a way that parallels the efforts of the Cubists. His abrupt shifts in space and time follow the workings of the mind as our thoughts jump around. And he insists that our minds participate in order to make sense of what’s on the page—just as they are working to make sense of the world.

Newmann’s collage contains a doubled photo of Joyce and various semitransparent overlays that mask a textbook drawing of a weird zoömorph. A form of jellyfish (periphylla), its multiple tentacles suggest viscera and or the snake-haired Medusa or the ensnaring Hydra that embattled Hercules. A theme of branching occurs throughout, matching bits of Chinese tortoise-shell tracery with old scientific illustrations of both invertebrates and serpent skeletons (“Nature’s artforms” the text says in German). Newmann follows the Surrealists in treating the hidden structures of the natural world as a mirror of the unconscious. (The periphylla live more than a thousand meters down in the dark depths of the ocean and only at night do they rise up to feed and breed near the surface, providing a perfect metaphor.) Hence the entire collage evokes the “riverrun” of the dream world of sleep and the “hitherandthithering” flow of unconscious association in the burgeoning puns of Finnegans Wake: “We may come, touch and go, from atoms and ifs but we’re presurely destined to be odd’s without ends,” Joyce writes; “Putting Allspace within a Notshell.”

For me, however, Newmann’s piece recalls the wide-awake stream of consciousness of Stephen Daedalus’s seaside musing in the third part of the first chapter of Ulysses [p. 37]. An alert interaction with the natural world, it begins with the famous line: “Ineluctable modality of the visible.” Stephen is walking along Sandymount Strand, absorbed in his own internal preoccupations, and yet paying attention to the “signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and seawrack, the nearing tide,” with his awareness trolling among the beached flotsam at his feet. He begins thinking about the role of the senses as mediators of the natural world outside the mind, and decides to close his eyes, shutting out the colors of the world, pretending to be blind. For a while he listens, tapping his way with his stick and contemplating the unsettling possibility that the entire world might somehow have become non-existent, and that he could be solipsistically lost forever “in the black adiaphane” of interior consciousness. Suddenly he opens his eyes; and the commonplace, and his own common place within it, strikes him with the force of revelation: “See now. There all the time without you: and ever shall be, world without end.”

When it comes to the world, we are both a part and apart.

In a 1939 text on the art of Max Ernst, Paul Eluard—one of the greatest of the Surrealist poets and a lifelong friend of Picasso—wrote:

It is not far – as the crow flies – from cloud to man; it is not far – by way of images – from man to what he sees, from the nature of real things to the nature of imagined things. They are of equal value. …Only when you have ceased to ascribe ideas to life will you be granted the belief that everything is transmutable into everything. A truly materialist interpretation of the world cannot exclude from that world the person who verifies it.

A video of Dana Newmann discussing her art work at Smink Interior Design in Dallas can be seen below:

Responses to “In the Realm of Surrealism: The work of Dana Newmann from 1969-2014”