Without art, the crudeness of reality would make the world unbearable. —George Bernard Shaw

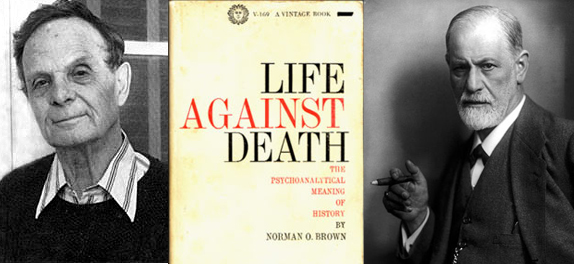

If you ask me what the most important, let’s say intellectually challenging, non-fiction, book written in the 20th century, it would have to be Life Against Death by Norman O. Brown. First published in 1959, when I read it in 1968 I found myself re-reading almost every page just to make sure what he said was what I thought he said. The sub-title is The Psychoanalytical Meaning of History. Brown was profound.

When he wrote LAD Brown was a professor of classics at Wesleyan University, and later at UC Santa Cruz, in California, where he died in 2002 at 89. During the 1960s the Movement raised him up to an icon. Remember the Movement?

Right at the start he writes, “This book is addressed to all who are ready to call into question old assumptions and to entertain new possibilities. And since new ideas will not come if their entry into the mind is subject to conformity with our old ones and with what we call common sense, this book demands of the reader—as it demanded of the author—a willing suspension of common sense. The aim is to open a new point of view.”

He explains that he began “a deep study of Freud” in 1953, so we know where he’s headed; his first chapter is called “The Disease Called Man” and immediately we are hit with Freud’s dictum, The whole edifice of psychoanalysis is based on the theory of repression.

Brown says, “The discontented animal is the neurotic animal, the animal with desires given in his nature which are not satisfied by culture. From the psychoanalytical point of view, these unsatisfied and repressed but immortal desires sustain the historical process.

“History is shaped, beyond our conscious wills, not by the cunning of Reason but by the cunning of Desire.”

In a chapter titled “Art and Eros” he says, “Freud many times quotes the artists in support of his psychoanalytical discoveries.” Freud admitted that, “The poets and philosophers before me discovered the unconscious; what I discovered was the scientific method by which the unconscious can be studied.”

Brown goes on, that “…art represents an irruption into the conscious. Art has to assert itself against the hostility of the reality-principle. Hence its aim, in Freud’s words, is the veiled presentation of deeper truth; hence it wears a mask, a disguise which confuses and fascinates our reason.”

The whole theory of art in Freudian terms stated simply is that “Art, if its object is to undo repressions, and if civilization is essentially repressive, is in this sense subversive of civilization.”

“Some of Freud’s formulations on the role of the indispensable third person suggest that the function of art is to form a subversive group…the aim of the partnership between the artist and the audience is instinctual liberation. Art seduces us into the struggle against repression.”

Brown goes on: “The function of art—Freud says ‘wit’—is to help us find our way back to sources of pleasure that have been rendered inaccessible by the capitulation to the reality-principle which we call education or maturity—in other words, to regain the lost laughter of infancy.”

He delves into an essay the German poet Rilke wrote titled “Ueber Kunst,” wherein he presents art as a way of life, “like religion, science, or even socialism” and “the sensuous possibility of new worlds and times.”

Of course the times are resistant. “It is only from this tension between contemporary currents and the artist’s untimely conception of life that there arises a series of small discharges [befreiungen], which are the work of art.”

Thus the dialectic between art and society derives from the artist’s contact with the ultimate essence of humanity, which is also humanity’s ultimate goal: “History is the index of men born too soon.”

Men, as well as women born too soon suffer, especially the poets. Whether they receive any succor from Freud’s ideas or not, Brown tells us, “Freud saw psychoanalysis as the third great wound, comparable to the Newtonian and Darwinism revolutions, inflicted by science on human narcissism…As we have argued elsewhere, the proper aim of psychoanalysis is the diagnosis of the universal neurosis of mankind, in which psychoanalysis is itself a symptom and a stage, like any other phase in the intellectual history of mankind.”

Nietzsche once commented, “We have art so as not to perish of truth.” And sublimated truth finds its way in the world as art. Art gives us enjoyment—“an enjoyment which, by the agency of the artist, is made accessible even to those who are not themselves creative. People who are receptive to the influence of art cannot set too high a value on it as a source of pleasure and consolation in life. Nevertheless the mild narcosis induced in us by art can do no more than bring about a transient withdrawal from the pressure of vital needs, and it is not strong enough to make us forget real misery.” [author's emphasis]

Freud labels all art and culture the “intoxicating media”—“For one knows that, with the help of this ‘drowner of cares’ one can at any time withdraw from the pressure of reality…it is precisely this property of intoxicants which also determines their danger and their injuriousness. They are responsible, in certain circumstances, for the useless waste of a large quota of energy which might have been employed for the improvement of the human lot.”

So art functions as a “drowner of cares” as well as an eruption of truth into the world, a paradox of immense proportions.

I have a theory, if I may call it that, that when Freud arrived in London in 1938, after having bribed his way out of Nazi-occupied Vienna, he was suffering from a painful cancer of his upper palette, and had made his doctor promise that when he had reached the point he could not tolerate it anymore, he must grant him a peaceful end.

Now the BBC went on the air in 1939, but experimental broadcasts began in 1932, and when Freud realized how intimately this “intoxicating medium” would enter into everyone’s parlors, he called his doctor and made an appointment for September 23. TV was too much for the man who had written Das Unbehagen in der Kultur.

In this book, published in 1930, titled unfortunately in English Civilization and its Discontents, Freud talks about these intoxicating substances and the indispensably powerful deflections “which causes us to make light of our misery.” He goes on: “Voltaire has deflections in mind when he ends Candide with the advice to cultivate one’s garden; and scientific activity is a deflection of this kind, too. The substitutive satisfactions, as offered by art, are illusions in contrast with reality, but they are none-the-less psychically effective, thanks to the role which fantasy has assumed in mental life.”

As the Greek dramatist Aeschylus said, Art is far weaker than Necessity, predating psychoanalysis by about 2,500 years.

At the end Brown posits psychoanalysis “as the missing link between a variety of movements in modern thought—in poetry, in politics, in philosophy—all of them profoundly critical of the inhuman character of modern civilization, all of them unwilling to abandon hope of better things.”

Which brings us back to the necessity of art.

Responses to “Immortal Desires & the Seduction of Art”