“I came home from work on April 3 and Alfredo was just gone,” Adrianna says. “His breakfast was on the table, nothing had been taken, not even his toothbrush.”

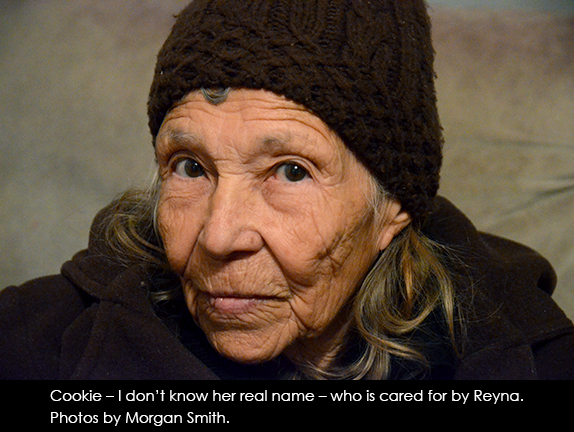

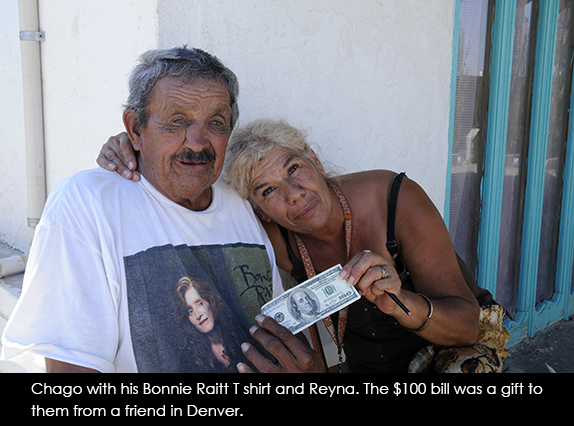

It’s May 19 in Palomas, Mexico and I’m at the home of Reyna Cisneros, the woman who founded an orphanage called La Casa de Amor Para Niños. Now she cares for older people who have been abandoned by their families and always has two or three in her small home. Adrianna is one of her daughters. Whenever I’m in Palomas, I stop by and try to give them a little assistance.

They then tell me how they had gone to every town in the area, talking to police officials, checking jails and asking for Alfredo. I’m stunned because I thought that the wave of violence that swept through Palomas a few years earlier had disappeared. It sounds, however, that he and two cousins had been kidnapped and are now dead and buried somewhere out in the desert.

Nonetheless, a few months later I write an article about how both Palomas and Juárez are making a comeback from that wave of violence that swept the whole border. Then a friend responds; he heads the coalition of churches that now run the orphanage and has been coming to Palomas at least once a month for more than a decade. He says, “It is interesting that the violence has been curbed but we should not think that the cartel has gone away. A couple of our people were face to face with the current head of the cartel in Palomas, recently, and it is definitely the head of Palomas to which all others bow.”

This all comes rushing back as I read the unfolding story of the killings in Iguala, a small city south of Cuernavaca and the disappearance of forty three students. On September 26, the students had come to Iguala for a protest. The police fired on them, six people were killed and then the police took the forty three away. It’s believed that they were then turned over to a gang called Guerrero Unidos. On October 4, twenty eight burned corpses were found in several nearby pits but initial forensic studies indicate that they are not the students. So who are these twenty eight, where are the forty three students and are any of them still alive? Dozens of people have been arrested, mostly police officers; the Mayor, José Luis Abarca, his wife, and the police chief – all suspects – have disappeared; and Benjamin Mondragón, head of the Guerrero Unidos was just killed in a raid by security forces. There have been enormous protests not only in Mexico but also cities like Berlin, Barcelona, London, Los Angeles, New York, Chicago, Montreal, Madrid, Brussels and San Francisco.

This follows an incident near Mexico City on June 30 where twenty two people were killed in what was originally called a “shoot out “ with Mexican soldiers but now is being deemed a mass execution.

Are these horrific incidents just the behavior of rogue police officers, soldiers and gang members or a symbol of the widespread way in which cartels are infiltrating and taking over governmental entities? Many observers believe that it’s the latter, that the staggering amounts of money gained from the drug trade are essentially being used to “buy” governments, and that the relative calm we have seen in some areas of Mexico like Palomas isn’t a symbol of lawfulness but rather of one cartel having crushed the opposition, reached a pact with local officials or simply taken over the local government.

If, in fact, what happened in Iguala is more than just a savage but isolated explosion of violence and cruelty, if it is really “government action” in the sense that it was mostly carried out by the local police/ criminals, then Mexico’s President Enriq ue Peña Nieto has a staggeringly complicated problem that could sink his administration and negate the reforms he has made in the areas of telecommunications, education and energy. For example, why would foreign oil companies risk investing in the oil-rich state of Tamaulipas, just across from Texas, when governments there are largely in the hands of cartels?

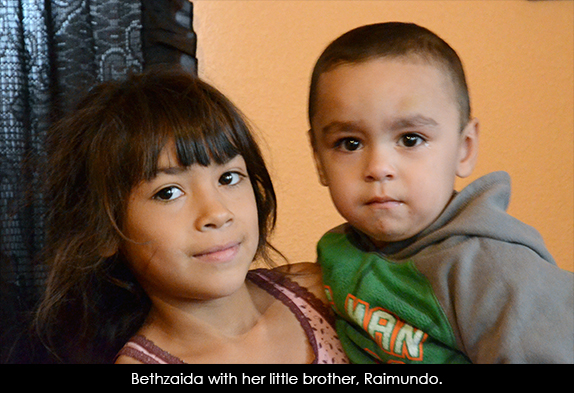

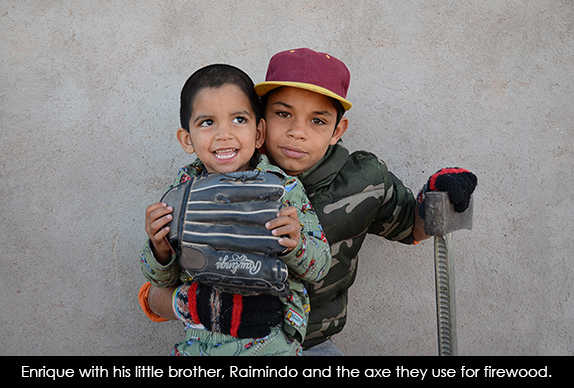

This Saturday I will be driving to Palomas and will visit Reyna and her family. Winter is coming and they’ll probably be outside, gathering firewood by hacking at mesquite bushes with a dull axe. Chago and Cookie, the two old people Reyna cares for, will be there as well as Bethzaida, Adrianna’s brilliant ten year old daughter who recites poetry and Enrique, thirteen, who will soon be going to a Shriner’s hospital in Los Angeles for an operation on his feet. They’ve always been poor but they can deal with that. However, what is terrifying is to think that they live in a town where the head of a cartel is “the head to which all others bow.” And that millions of other Mexicans may be in the same boat.

Responses to “Iguala”