Editor's note: This was originally a lecture given at OASIS Albuquerque on Monday, November 17, 2014.

I want to talk today about an issue which has been, all my adult life, as central a concern of mine as racism has been, and that is income inequality in America (and the two—race and income inequality—are, of course, intertwined).

What are the causes and effects of the great and increasing maldistribution of income in this country? And what should be done about it—and why?

I want to talk about this subject in the context of my own personal story—because I want you to know that if I can come to see these things, anyone can. Historian Richard Lowitt wrote a biography about me called, Fred Harris: His Journey from Liberalism to Populism, and he did a pretty good job, I guess, but I want to tell the story myself.

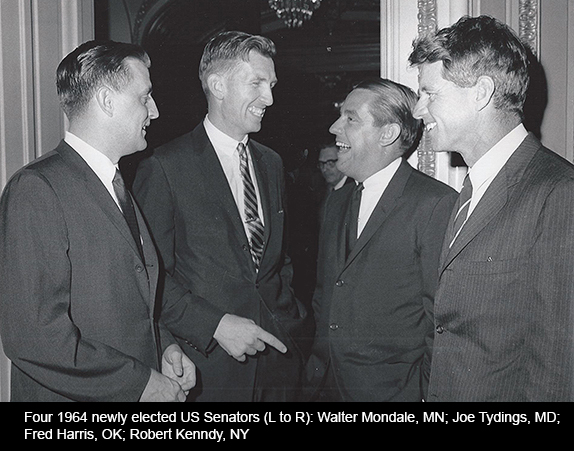

I was twice elected to the United States Senate from Oklahoma. The first time in the Fall of 1964--when I was thirty-three years old. And I went to Washington with all the expertise in national economic policy (and, for that matter, in national security policy) that eight years in the Oklahoma State Senate affords one.

Sure, I had grown up as a Franklin Roosevelt progressive Democrat (although my family, a poor and working-class family, often having faced some early, hard-scrabble years, took little interest in politics). And, sure, at the University of Oklahoma, I had studied economics, along with political science, history, and law.

But when I first got to Washington, mine was still, like that of the followers of Franklin Roosevelt, a kind of “conscience” politics. The government ought to do right because it was the right thing to do, morally right. Those of us well-off ought to help those less fortunate out of the goodness of our hearts, with the federal government a kind of necessary funnel for our charity.

And then, rather right away soon after I arrived at the Senate, I was appointed to the Senate’s most powerful committee, the Senate Finance Committee, which because of its broad jurisdiction, covering taxes, foreign trade, social security, Medicare, and welfare, had, and still has, a central role in making national economic policy. And soon, too, I was, together with New York City mayor John Lindsay, a guiding leader of President Lyndon Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, the Kerner Commission, established partly at my suggestion following the terrible riots which occurred in the African American sections of most of America’s cities during the “hot summer” of 1967—a Commission which found, quite famously, that “America is moving toward two societies, one white, one black, separate and unequal,” and that institutional racism was the basic, endemic and awful cause. And then the Commission recommended, in addition to vigorous enforcement of the recently enacted civil rights laws, great new federal programs, particularly for jobs, education, and training.

My friend, the then Secretary of Labor, Willard Wirtz, summarized the Kerner Commission’s findings of fact by saying, “In the words of that great American philosopher, Pogo, ‘We have met the enemy, and he is us!’” And another admired friend of mine, the wonderful then Secretary of Health Education and Welfare, John Gardner, backed our Kerner recommendations by declaring, “We are in deep trouble as a people, and history will not deal kindly with any nation which will not tax itself to cure its miseries.”

But my laborer, cowboy, cattle trader father, then eking out a living on a small farm in southwestern Oklahoma, struggling to pay the medical bills for my mother who was suffering in a years-long coma from a stroke that eventually killed her—he loved me, my Dad did, and believed in me, but the way he heard what we said on the Kerner Commission was: “Mr. Harris, you should, out of the goodness of your heart and because of your Christian duty, pay more taxes to help poor black people who’ve been rioting in Detroit.”

My Dad’s response was something like: “To hell with that! I’ve got enough troubles of my own. I’m barely making a living, and I’m already paying too much tax. What about me?”

My Dad’s feelings were understandable. He had a right to have his interests looked after, too.

It became increasingly clear to me that you can’t have a mass movement without the masses. You can’t accept that some people will follow a politics of self-interest, will vote their own self-interest, and the rest of us should quietly vote in their interests, too, ignoring our own, which are just as valid.

Governments are more than their basic documents. The U.S. Constitution is, indeed, a splendid instrument, our system of representative government a marvel. But they work, if they do, because of the social contract that underlies them—because we have, in a way, all agreed to live together in the same “house” and to share in duties and expenses on some kind of fair, not necessarily equal, basis.

The trouble is, I began to say, that a few rich people and big corporations have most of the money and power in this country. That the rest of us, who have too little, who live together in our “house,” who, in other words ought to be in our coalition, don’t have to love each other—I wish we would, but we don’t have to. All we have to do is recognize that we have common interests which overlap and that if we get ourselves together, we are a majority and can take back our government.

I then became the National Chair of the Democratic Party in 1969. I did so primarily to reform the Party, to make it live up to what it called itself, which had not earlier been true. I appointed a Reform Commission with Senator George McGovern as chair, and I made up the Commission’s membership in such a way as to assure the kind of reforms that the Commission would eventually come up with—full representation of women and minorities, open and full democracy in all the Party’s processes, from delegate selection to adoption of the party’s platform. I wanted the Democratic Party to be a grass roots people’s instrument.

I also appointed a Democratic Party Policy Council. I wanted to put the national Party on record for an end to the Vietnam War which I had come to see was a mistaken and immoral war, not in the interests of America’s people. And, too, I wanted to start the Party down the road toward what I had begun to call the New Populism. I soon wrote a book—The New Populism—spelling out what that meant. The New Populism, I said, is against concentrated economic and political power. It’s for a more fair distribution of income, wealth, and power. It’s for what Abraham Lincoln meant when he spoke so succinctly and passionately about “government of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

I had always thought that my duty as a senator was a dual one: both to work within that national forum, the Senate, to which Oklahomans had so generously elected me, to further the best interests of all the people--and at the same time, to work on the outside to help change the climate in which the Senate operated. I’d served on the Kerner Commission and, later, as National Chair of the Democratic Party while at the same time serving as a US Senator—which was one reason, perhaps, why about this time the Republican editor of the Perry, Oklahoma weekly newspaper wrote: “Oklahoma has two United States Senators. One doesn’t do anything, and the other does too damned much!” I was the one who did too damned much.

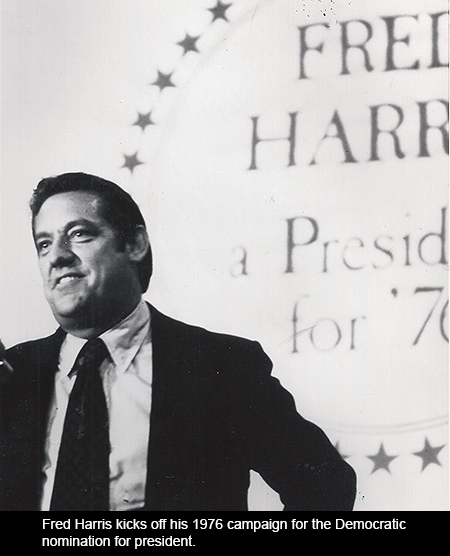

But I didn’t run a third time for the US Senate. I thought I’d done what I could there. I wanted to work fulltime outside the Senate. I wanted to run for President. I thought that a presidential campaign, even a good though unsuccessful one, could make a difference. So, I eventually announced as a candidate for the 1976 Democratic nomination for President.

Before I go any farther, though, here’s a ‘spoiler alert”: I was not elected. You probably already knew that.

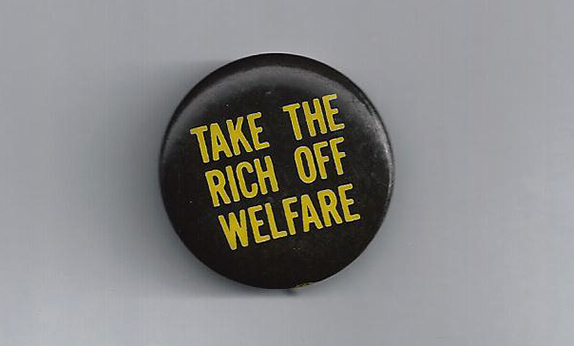

But I am especially proud of the fact that I ran for President of the United States and that, doing so, I said exactly what I believed in. One of our campaign slogans was: “The Issue is Privilege.”

In televised presidential-candidate joint debates, in appearances on programs like Meet the Press and Face the Nation, in street rallies, great auditoriums, and in countless living rooms, I talked about how the gross and increasing inequality of income and wealth in America was our basic problem. I said, “Too few people have all the money and power, and most people have little or none.” In terms of how economic and political privilege thwarts the will of the people, I called attention to the real day-to-day problems of people caused by “heavy and unfair taxes, bad or nonexistent housing, inadequate and costly medical care, inflated food, utility, and other prices, high interest rates, exorbitant military expenditures and waste, cynical and interventionist foreign policy, and low wages and unemployment.” I talked about how rich farmers and others like them enjoyed huge government subsidies and how they and others were being given unconscionable tax breaks. I mentioned Nelson Rockefeller, as an example; he’d admitted before a congressional committee that on his great income in 1970 and 1971, he’d paid zero individual federal income tax. I said, “We ought to sue him for nonsupport.” And I always concluded my remarks by saying, “There is plenty of money to do what needs to be done in this country, if we take the rich off welfare.” That became our most popular campaign button: “Take the rich off welfare.”

What happened? National reporter Charles Mohr put it this way in the New York Times: “When Mr. Harris began to campaign in the summer of 1974, there seemed to be several possible outcomes. One of the most likely was that, sooner or later, commentators and politicians would begin to denounce him as a radical. Another possibility was that he would make no significant impact at all and would go unheard. Instead, something else quite different happened. Rather than “ex-communicating” Mr. Harris, many liberals in his party embraced his populist doctrines.”

So did some of the other candidates, as nationally syndicated columnist Jules Whitcover wrote about me and my campaign: “Other candidates, notably Carter and Udall, often picked up on his themes, in sometimes toned-down phrases, sometimes in identical ones, delivered with less aggressiveness.” And Charles Mohr, again, described the same phenomenon for the Times in this way: “Other liberals, such as Representative Morris K. Udall of Arizona and Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana, echoed many of the words and even some of the rhythms of the Harris campaign, particularly his unrelenting attacks on monopolistic power wielded by the ‘giant corporations,’ his appeals for more equality of opportunity and his demands for social justice. Even more conservative candidates, such as Senator Henry M. Jackson of Washington and former Governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia, seemed to borrow elements of the Harris gospel.”

So, we had some impact.

But, remember that name, Jimmy Carter? He was the one nominated and elected. I was not.

I decided it was time to get out of Washington, to go back out in the country. One of my Senate colleagues who had come to the Senate the same year I did—after he got beat for a second term—had joined a lobbying DC law firm for a reported drawing account of a million dollars a year. I didn’t want to do something like that.

Instead, I accepted a position as a tenured full professor of political science at the University of New Mexico. It is true, as an oldtime Oklahoma political figure, Wilburn Cartwright, once put it, “Politicians go where invited and stay where welcome.”

That now-famous and always factual, fiery and fun, great Texas populist Jim Hightower was once, about this time, asked by a reporter for the Fort Worth Star Telegram: “Is it true that you were the campaign manager for Fred Harris when he ran for President?” And Hightower said: “That’s true. I made Fred Harris what he is today . . . a college professor.”

So, I gave up being a politician.

When I once said that in a public forum, one guy said to me afterwards, “Not true. The only cure for being a politician is formaldehyde.” What I should say, then, I guess, is that I gave up running for office. But I didn’t stop pushing for what I believed in. I had always thought of myself as a teacher. Now, I taught fulltime. I wrote books, a lot of them. I worked for and contributed financially to good candidates. I was active in Party affairs, was a delegate to every National Convention, and even was drafted into becoming chair of the NM State Democratic Party for a time.

And I never stopped agitating. Haven’t yet.

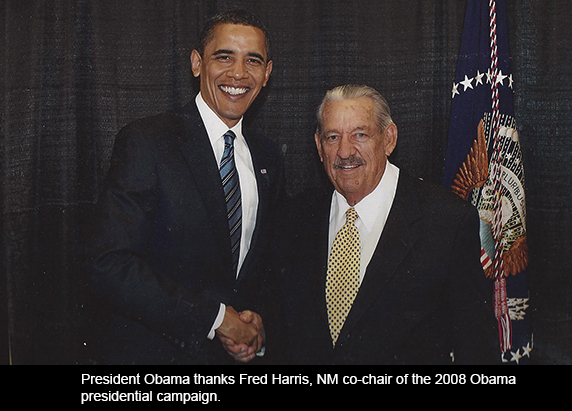

I’d like to say that this all paid off in decreasing the inequality of income in America. Maybe it did some, off and on. We made some progress on the connected problems of race and poverty during Democratic presidential administrations, fell back during Republican ones. More lately, I exulted in, had helped in, the election of a great progressive Democrat, Barack Obama, as the first African American president ever. I know Barack Obama, and I can say to you that he is the smartest and best-motivated president I’ve ever had anything to do with. I have strongly backed his policy initiatives, I have taken pride in his successes, and I’ve fought hard against despair when he’s been stymied by mean-spirited intransigence and obstruction.

And, so, now, where are we in this country?

Sad to say, the maldistribution of wealth and income in America is worse than when I was first writing and speaking about it and campaigning on a platform that called for doing something about it.

So, here’s a quick recitation of today’s bald facts:

- The top 10% of earners took in more than half of the total income earned by Americans in 2012 (the highest level recorded since the government began collecting this data a hundred years ago.). [Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Picketty]

- The top 1% of earners took in more than one-fifth, 22.5%, of 2012’s total income, one of the highest levels since 1913. Since the recent Great Recession, the top 1% of earners have captured a whopping 95% of all income gains in this country.

- In the 1960s, the CEOs of major US companies who made roughly 30 times as much as their ordinary workers made; today, they make something like 300 times what their employees make. [Paul Krugman]

- This past September (2014), a Federal Reserve Bulletin reported that the wealth gains in America since 1989 all went to the top 3%, while the next 7% of Americans only stayed even, and the bottom 90% of Americans experienced a steady decline in what little wealth they had. Today, the 400 richest Americans have more wealth than the bottom 150 million Americans. [Robert Reich] With a generous tax loophole, the top 25 hedge fund managers, for example, made an average of one billion dollars each in 2013. We’ve returned to the so-called Gilded Age of the Robber Barons of the Roaring Twenties, before the Great Depression. And that might be a warning to us.

- Put that last fact beside some of these additional ones:

- In 2012, real median household income in America was 8.3% lower than in 2007. [U. S. Census] From 2000 to 2009, worker productivity increased at an annual rate of 2.5%, and it has continued to grow, increasing corporate profits, but not real wages. In 2013 alone, for example, US corporate profits rose five times faster than wages. [Thomas B. Edsall]

- During the first two years of the “recovery” after our recent Great Recession, the mean net worth of households in the upper 7% of wealth distribution rose by 28%, while the mean net worth of households in the lower 93% fell farther, by 4%.[Pew Research Center]. Today, median household income in America is 8.6% below what it was in 2000.

- Slightly over 11% (11.3%) of Americans were living in poverty in the year 2000. Today, despite a very slight decline last year, nearly 15% (14.6%) of our people—1 in 4 of our children—are poor. The number of households living on $2 or less in income per person per day in a given month in America went up from about 636,000 people in 1996 to about 1.46 million people in early 2011, a percentage growth of such poverty of 130%. [National Poverty Center]

- Cash assistance benefits for America’s poorest families fell again in purchasing power in 2013, and those benefits are now, in 37 states, at least 20% below in purchasing power, adjusted for inflation, than they were in 1996. [Center on Budget and Policy Priorities]

- And consider what we’re now doing about all this. As economist Joseph E. Stiglitz puts it, “So corporate welfare increases as we curtail welfare for the poor. Congress maintains subsidies for rich farmers as we cut back on nutritional support for the needy. Drug companies have been given hundreds of billions of dollars as we limit Medicaid benefits. The banks that brought on the global financial crisis got billions while a pittance went to the homeowners and victims of the same banks’ predatory lending practices.”

The result of all this?

Look at where we stand among nations of the world, comparing the incomes of the richest 10% of the people with the poorest 40% (the Palma Method). Where are we? We rank 44th out of 86 countries, well below every other developed country in the world and even one spot below Nigeria, for goodness sake! [Max Fisher and Dylan Matthews]

How did things get this bad?

One cause is not so obvious, perhaps: new technology. A lot of the old blue-collar jobs that used to put and keep American workers in the middle class don’t exist anymore.

But other causes of our bad income inequality are quite obvious. We’ve cut taxes for rich people and corporations. Strange but true, in a country that professes to believe in the value of work, we tax money earned from work a lot harder than we tax money earned from money. And when President Obama tried to get restored the unwise and unfair tax cuts for the rich of the George W. Bush administration, he was harshly blocked—and was able to get only a smaller portion of what he asked for.

And while CEO pay skyrocketed, as I said earlier, worker’s wages stagnated or fell. One reason was that union power was shrinking. Not long ago, I saw where the portion of American labor represented by unions had sunk to only 16 percent, and, since then, that percentage has dropped even farther. Still, the right wingers and the corporations fight madly against unions and union organizing. Maybe this isn’t exactly whipping a dead horse. But it certainly seems like kicking a sick one. Studies show that one of the significant reasons why neighboring Canada has a much better distribution of income than America does is because they are a country of strong unions which have been able to stand up to the corporations, fight for their rights, and keep a fairer share of burgeoning corporate productivity and profits from their labor.

We’ve shipped a lot of American jobs overseas to unbelievably low-wage countries. Tax subsidies which President Obama has been trying unsuccessfully to get repealed have actually encouraged this flight. Free trade agreements have allowed our own runaway plants, as well as indigenous local foreign-country industry, to penetrate America’s great market with goods, the lower prices for which result from the fact that they are in effect subsidized by the home country through a low-wage system and a lack of environmental controls that come nowhere near matching our own. This unfairly competitive pressure has put a lot of American workers out of jobs here at home and has held down, or depressed, the wages of those who still have jobs here. [Joseph Stiglitz]

We took important federal safeguard regulation off the big banks and the financial industry, and they did what I know from experience a horse will do when it breaks into an oat bin: they gorged themselves until they foundered. They crashed, taking the rest of us with them. In the process, we got the recent Great Recession, and we still have 5.7 million potential workers sidelined by it, a lot of them, older workers in particular, maybe never to work again in decent-paying jobs. [Economic Policy Institute]

With most American workers having no union to fight for them, unable themselves to make demands for fear their employers could turn their jobs over to some of the great numbers of unemployed people, willing to take a job at almost any wage—the median wage having stagnated since 2000, and for the lower one-fifth having declined 4.5% [Economic Policy Institute]—American workers should have been protected by the federal minimum wage. But they weren’t—because the federal minimum wage, with inflation, had lost much of its purchasing power, had become more of a ceiling than a floor, and Republicans in Congress blocked any action that would have brought it up to date and kept it current.

And when our national economy was in desperate need of jump-start stimulus, President Obama couldn’t get enough of it out of Congress—and still can’t. British economist John Maynard Keynes famously wrote in the 1930s—and this has been the policy followed by every US President, Republican and Democrat, ever since, whether they admitted it or not—that the basic cause of recession or depression, to put it simply, is lack of spending, and the cure is for the government to lower taxes on the middle class, to leave more of consumers’ money in their own hands, so they can spend it to benefit lower and middle class people, or to increase government spending, even if government has to borrow the money, and, that way, pump more money into the economy, into the hands of consumers who will spend it, or some combination of both remedies.

And, when used, this policy has worked. President Franklin Roosevelt was elected in 1932, in the midst of the terrible Great Depression. His new government began almost at once to borrow and spend, probably not because Roosevelt personally understood or even agreed with the principles that Keynes would soon be writing about—as a matter of fact, Keynes, later Lord Keynes, actually had once come to the White House for a personal talk with President Roosevelt, but afterward, the puzzled chief executive said to an aide, “That fellow should have been a mathematician.” No, President Roosevelt hugely increased government spending because he thought there were important things that needed doing and that this would put people back to work. His actions were a success, the nation began to climb out of the depression, until 1936, when the deficit hawks and debt-fearful pushed the government back toward tighter money and austerity—“We ought to live within our budget.” just the wrong medicine the economy needed. What happened? We began to slip back into recession. (Similarly, a modern example of the wrong medicine, an article in the New York Times reports that Japan’s economy has fallen back into recession after increasing its consumer sales tax.)

But back in the United States, not too long after our 1936 wrong medicine, the government began to spend again, massively, and we soon had full employment and a permanently humming economy again. Too bad that this great spending was for World War II, but no question, it worked, economically.

Presidential candidate Richard Nixon got elected, among other things, by running against the Democrats’ “Keynesian Economics.” But he thereafter came into office during the worst recession since the Great Depression, and, as I used to say, I thought quite cleverly, “President Nixon soon embraced Lord Keynes like they were going steady.” I quit saying that after an incident in a campaign swing of mine through Pennsylvania. One night, when I had again used that statement there before a college audience, a young man came up to me afterwards and said, “That was really clever the way you said Nixon was gay.” I said, “I didn’t mean to say that Nixon was gay; I don’t think Nixon was gay.” And the young man immediately said, “Well Keynes was.” I found out the young man was correct. So, I began to say, after that, that Nixon, in economic trouble, embraced Keynesianism. He did. And it worked.

Maybe you remember that the United States came out of World War II with a national debt that was colossal, about 140% of our Gross Domestic Product. Today’s rightwing deficit hawks would have said, “Cut the budget; we’ve got to have austerity.” But we didn’t do that. Instead, we began to invest in ourselves. Remember the GI Bill of Rights, for example? It took unemployed returning servicemen and women and gave them first-rate education and training. It helped them buy homes, which somebody had to furnish the materials for and somebody else had to construct. This program was terribly important and economically uplifting for the millions of men and women who took advantage of it. But it also resulted in a huge and lasting boost for the nation’s economy. What was wrong with that? And what was wrong with President Dwight Eisenhower’s massive Interstate Highway program, the greatest public works project since the days of Rome and one in which the federal government paid 90% of the cost. Look at all the people that great program put to work immediately. And think about what a giant and long-lasting shot in the arm it was for our economy.

What was the result of all these kinds of Post-WWII investments in ourselves? Did the national debt overwhelm our Gross Domestic Product, the government’s basis for its ability to pay? Is that what happened? Did the United States go bankrupt? No, to the contrary, we proved what Keynes had said, what my tough cowboy kind of Dad said more simply, “You have to spend money to make money.” The debt as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product, our ability to pay, shrank and shrank, and shrank some more. Because our ability to pay, our Gross Domestic Product on which the federal government collects taxes, grew and grew, and grew some more.

There are so many jobs that need doing in this country—from constructing highways and water and sewer systems, for example, or from fostering needed alternative energy sources, or from expanding affordable quality childcare. But Congress wouldn’t go for enough of this kind of stimulus, and the states cut back, too, and this helped allow America’s terrible inequality of income to worsen to the sorry level it is now.

What difference does it make that we have so much inequality of income and so much poverty in America—aside from the great harm it means for so many real people (a pretty big “aside.”)

America’s middle class has shrunk and shrunk, as so many millions of our people have fallen out or have been forced out of the middle class and into poverty, while the ranks of the rich have swollen. Most authorities think it is difficult to even have a true democracy without a large and stable middle class. Economic power translates into political power. Daniel Webster said that if we’re to preserve our kind of democratic system, no person should be so rich as to be able to buy other people, and no person should be so poor as to have to sell. Think of the rich and archly rightwing Koch brothers, or the giant corporations whom the US Supreme Court has said are “people,” with freedom of speech, and therefore cannot be limited in how much they can spend of their special interest money in political campaigns.

And as Paul Krugman has written in the New York Times, “Surveys of the very wealthy have shown that they—unlike the general public—consider budget deficits a crucial issue and favor big cuts in safety-net programs. And, sure enough, those elite priorities took over our discourse” as President Obama tried to shock us out of the Great Recession.

Our widening inequality of income suppresses economic growth. Why? It’s middle class people—if we still had them all—who would spend more of their income than rich people. As Nobel economist Joseph Stiglitz has written, “Our middle class is too weak to support the consumer spending that has historically driven our economic growth.” And it’s difficult to manage and stimulate our national economy when we have so many poor people. Lowering interest rates doesn’t help people who have nothing, or little, to borrow against. Cutting taxes doesn’t stimulate spending by people who pay little or no taxes because they have little or no income.

And rich people are living longer than poor people—because of material and social conditions and the fact they get more food and better nutrition and medical care. Talking about the top and bottom 10% in this country, in the 1980s, rich people lived an average 2.8 years longer than poor people. By the 1990s, that gap had more than doubled, to 4.8 years, and it’s continued to grow since then. [US Department of Health and Human Services]

Income inequality produces education inequality. Take higher education alone, and talking about people in the top and bottom 25%, of people born in America in the 1960s, 5% of poor people went to college and 36% of rich people did. One generation later, of people born around 1980, the number of rich people going to college jumped by 20%, while the number of poor people doing so grew by only 3%. Just 30% of American adults today have a higher level of education than their parents did. And look at the disparity in income: between 1979 and 2012, the annual gap between what an American family with two college graduates and a family of high school graduates make grew by $30,000 after inflation. [Edmund Porter]

And it’s a cycle. Since those with more and better education wind up earning more, inequality of income produces inequality of education, and, in turn, then, inequality of education produces more inequality of income.

What is to be done, then?

Since the major causes of the inequality of income problem are quite obvious, so are most of the major solutions. Thomas Piketty’s greatly acclaimed and bestselling recent book, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, makes clear that gross inequality of income can be ameliorated by government action. Because as Steven Rattner’s op-ed piece in the New York Times documents, stating: “Before the impact of tax and spending policies is taken into account, income inequality in the United States is no worse than in most developed countries. . . However, once the effect of government programs is included in the calculations, the United States emerges on top of the economic heap.”

Basically, we know what needs to be done, and we know what works. A more progressive tax system, making rich people and giant corporations pay more of their fair share. Stopping tax and spending subsidies that now redistribute wealth and income in the wrong direction. Strengthening unions and eliminating the legal and other barriers that so much now impede the organization of America’s workers. Raising the federal minimum wage (which if we raised it to just $10.10, as President Obama is proposing, would give 30 million American workers a total increase of $51 billion in new income, which would also be a giant boost to the nation’s economy, while at the same time cutting billions of dollars in federal safety net programs. And raising the minimum wage would not just help the working poor, it would bump up the wages of the middle class, as well.) We also need re-regulation of big banks and big finance. And jobs, jobs, jobs. More stimulus. More investment in ourselves, investment that will help right now but also bring about sustained and permanent economic growth—investment in education (especially in early childhood education), investment in training, in science, alternative energy, and technology. We must join President Obama in working to hold down increases in college tuition, and we must join with Senator Elizabeth Warren to find a way to forgive or ameliorate the existing and crushing student debt—37 million people owe $1 trillion, a great drag on our economy---and we must seriously rein in future interest rates and borrowing costs for college students.

We know what needs to be done, but will we ever do it?

I can’t guarantee that, of course, but I think we will. Why am I optimistic? Because the spontaneous Occupy Wall Street protests against the one-percenters, which first flared up in 2011, first in Zucotti Park in Manhattan, then in cities all across the country, forcefully helped to put the problem of rising inequality of income in this country squarely back on the public agenda. Earlier, my fellow Oklahoman, Elizabeth Warren, whom I know and admire, got herself elected to the US Senate by talking populism—and she’s now fighting for it on the national stage and has just been brought into the Senate Democratic leadership group. Another terrific populist, Bill de Blasio, was recently elected Mayor of New York City. Federal Reserve chair Janet Yellen has sounded the alarm about rising economic inequality, and even His Holiness Pope Francis has condemned unrestricted capitalist greed and spoken out for the need to end poverty and curb income inequality. President Barrack Obama, as you know, made a major address, declaring that inequality of income is the central issue of our time and saying what we should do to ameliorate it.

I believe that just as the present climate-change deniers must eventually see that their own self-interest requires a change in their thinking and action, those who now fight efforts to bring about a reduction in America’s terrible income inequality will also eventually accept the logic that, as my old friend Jim Hightower says, “Everybody does better when everybody does better.” The polls in this country already show that the American people now both agree that income inequality is a serious problem which must be solved and that a majority supports the obvious major solutions which I’ve here discussed.

And, yet, in the 2014 midterm elections, Democrats suffered historic levels of defeat. True, there were many more Democratic-held posts up for election than Republican ones. And true, the President’s party virtually always loses seats in Congress in the off-year election—because many of those who voted the President into, or back into, office do not return to the polling places in the elections that are held two years later. But these factors are not sufficient explanation of the stark fact of the 2014 Democratic losses nor the large margin of those losses, nor the fact that most Democratic candidates got only a minority and decreasing share of white, working class men—a group which was a vital part of the old Franklin Roosevelt coalition.

I think about the words of President Franklin Roosevelt on the eve of his 1936 reelection. Roosevelt said: “Government by organized money is just as dangerous as organized mob. . . I should like to have it said of my first administration that in it the forces of selfishness and of lust for power met their match. I should like it said of my second administration that in it these forces met their master.”

Who talks like that today? Well, for one, Senator Elizabeth Warren does. In an op-ed piece in the Washington Post, she wrote that we need an agenda of action in Congress, continuing: “But the lobbyists’ agenda is not America’s agenda. Americans are deeply suspicious of trade deals negotiated in secret, with chief executives invited into the room while the workers whose jobs are on the line are locked outside. They have been burned enough times on tax deals that carefully protect the tender fannies of billionaires and big oil and other big political donors, while working families just get hammered. They are appalled by Wall Street banks that got taxpayer bailouts and now whine that the laws are too tough, even as they rake in billions of profits. If cutting deals means helping big corporations, Wall Street banks and the already-powerful, that isn’t a victory for the American people—it’s just another round of the same old rigged game.”

And I am confident that an Elizabeth Warren could have won most of this year’s Senate races which the Democrats lost. Consider the fact that in three of the reddest states—Alaska, Arkansas, and South Dakota—where the voters elected conservative Republican senators, they also voted to increase the minimum wage. In three other states where Democrats who ran as populists like Elizabeth Warren—Senator Al Franken of Minnesota, Senator Jeff Merkley of Oregon, and Senator-elect Gary Peters of Michigan—these Democrats won their races going away. Nationally, the Democrats lost whites without a college degree by 30 points, Senator Merkley, for example, by contrast, narrowly won a majority of this group’s votes. In our own state of NM, Senator Tom Udall, whom studies show has the second most progressive record in the US Senate, handily won reelection while conservative Republicans were winning so many of the other NM races. The same can be said of NM’s two deeply principled and progressive Democratic US representatives, Ben Ray Luján and Michelle Luján Grisham, who were also easily reelected.

Nationally in 2014, there was not a coherent and sustained and national Democratic economic justice message. Most everywhere, Republican candidates attacked President Obama, while so many Democratic candidates were afraid to be seen with him. Conservative Republican candidates continued, for example, to speak with alarm about the great federal deficit and the need to cut spending, although under Obama the amount of the federal deficit has declined in each of the last five years and is now less than half what it was when he took office; it is this year an estimated 2.8% of Gross Domestic Product, markedly smaller than the 9.8% it was when Obama was elected. Still, only 19% of Americans think the deficit has gone down under Obama; over half of them think it’s gone up. Whose fault is it that the people still believe things like that?

During the last campaign, I am sure that, not counting telephone calls, I received at least 35 national Democratic emails a day—virtually none of them ever mentioning an issue, some of them saying we’re running ahead, some of them, even on the same day and from the same source, saying we are severely threatened, but all of them saying send us more money. I kept wishing that at least every other email might mention Obama and Democratic accomplishments, might say, for example, here are some talking points to tell your neighbors or write letters to the editor about: that since President Obama took office at a time of the greatest economic crisis since the Great Depression, unemployment has dropped from 10% to less than 6%, and ten million new private jobs have been created (more than 4 times more than were created during the 8 years of President George W. Bush), that Obamacare is working, that 10 million more Americans now have health insurance and millions and millions more are getting Medicaid—greatly reducing misery in this country and creating untold numbers of new health-industry jobs.

National Democrats have a clear and solid record and program for reducing income inequality. Why wasn’t that the persistent, consistent, and insistent core Democratic message in 2014?

I hope and believe that it can and will be the Democratic message in 2016, when the odds and the structural facts will be more favorable to the Democrats than they were in 2014.

But back again, finally, to the question I posed earlier: Will we ever do what needs to be done in America? I’m hopeful, optimistic, but I can’t say for sure that we will. I do know this for sure: there is existential value in the struggle itself, and each of us must do whatever he or she can do.

Thank you.

Responses to “Greatest US Challenge: Income Inequality”