“There’s a certain slant of light,” Emily Dickenson wrote, which can strongly affect us, stealing into consciousness “on winter afternoons” in particular. When we are struck by it, she continues:

Heavenly hurt it gives us,

We can find no scar

But internal difference

Where the meanings are.

It’s an odd sensation of separateness and earthly abandonment, delivered by an apprehension of light. Dickenson says it is beyond our capacity for learning or instruction and sealed with “despair.” She calls it “an imperial affliction / Sent us of the air.”

When it comes the landscape listens,

Shadows hold their breath,

When it goes ’tis like the distance

On the look of death.

I thought of Dickenson’s intuition, an intimation of mortality drawn from an experience of light, while looking at Gloria Graham’s recent photographic works. Dickenson felt oppressed by the angled light, saying it was “like the weight of cathedral tunes.” But Graham discovers in such slanting light something more akin to “the unbearable lightness of being.”

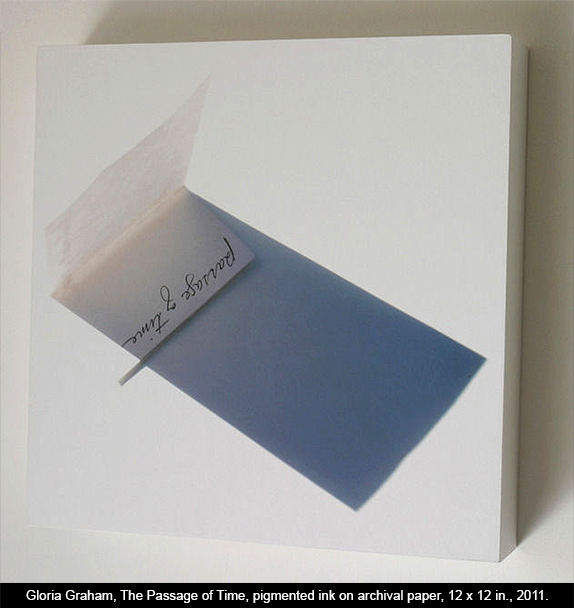

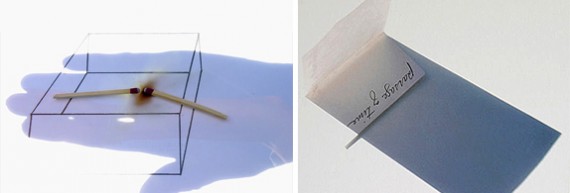

One photograph in particular sets the mood and serves as a reference point. A piece of paper has been folded and set down in the raking light, casting a long rectangular shadow across the image. Near the fold, and just inside the shadow, we can make out some (upside down) handwriting on the paper: The passage of time.

Apparently Graham has been photographing some of her old drawings, crumpled and torn, just before she ultimately destroys them, burning them in a kind of private studio ritual of purging the past. According to a gallery statement, she photographed the drawings outdoors at 3:00 pm in the brilliant afternoon sunlight of New Mexico. This anecdotal information, however, isn’t really necessary to respond to the haunting beauty of these images or to be intrigued by the mystery of their content. But it sheds light on them and gives them a certain slant. We recognize that the photographs contain a memorial purpose, and that they are a record of transience.

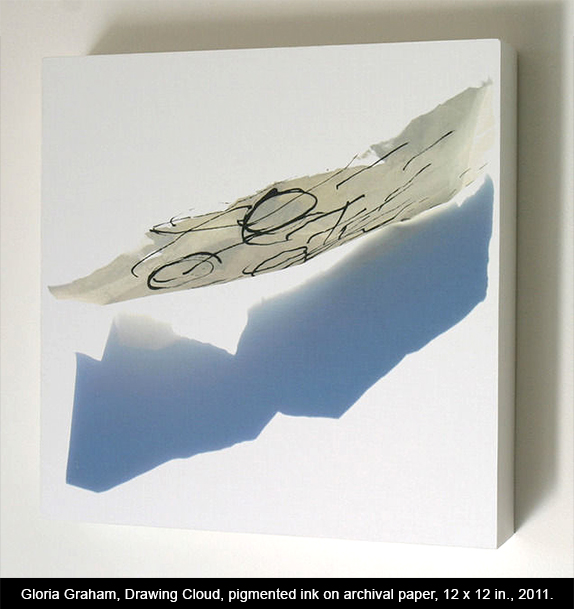

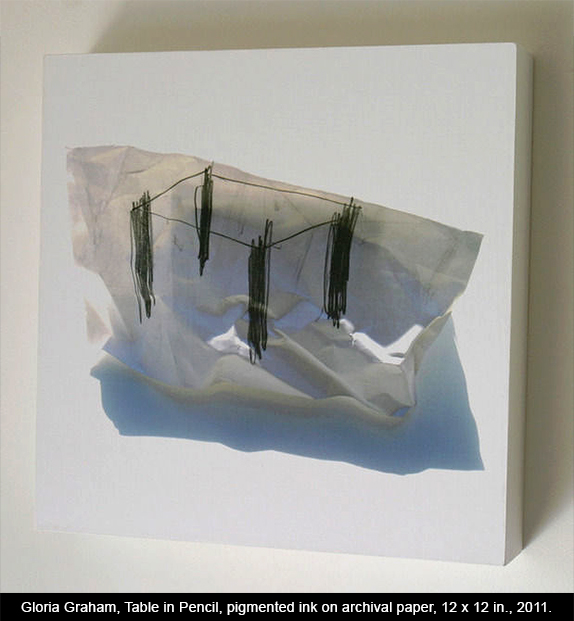

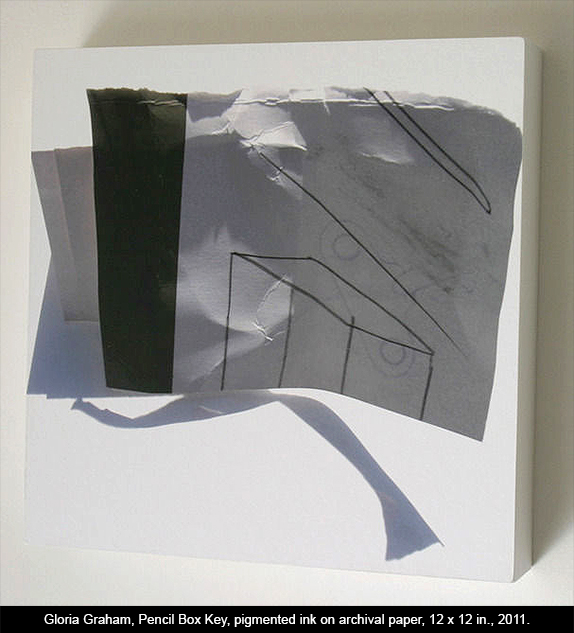

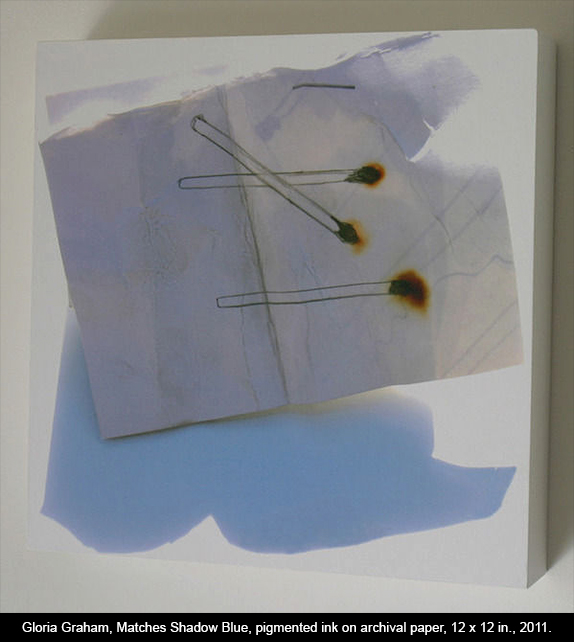

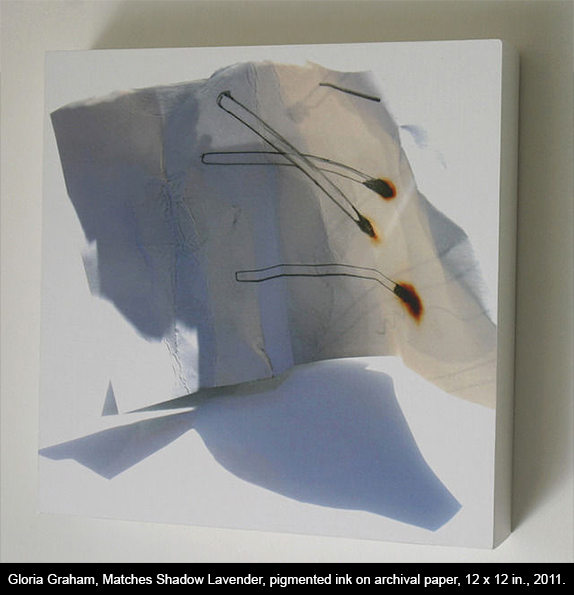

They are digital photographs, printed with pigmented ink on paper that is then stretched onto 12-inch square boards. So they are like memorial plaques or trophies, mounted on the wall. Going outdoors to photograph, Graham places a discarded drawing on a bright white sheet in the intense sunlight, where it casts a strange and irregular shadow. The light bleaches away any sense of ground, and both the crumpled drawing and its luminous shadow appear to float against the dematerializing whiteness. The shadow rakes in the slanting light, spreading in often unpredictable counterpoint to the crimped drawing paper and creating unexpected shapes, especially if any part of the drawing has been folded or torn.

In the camera’s interpretation, the shadows also take on a breathtaking range of subtle colors and tones. They become like thinly brushed washes of color, suffused with an internal light of their own. Instead of indicating light’s absence, the shadows seem to transmit light. They can even appear to be delicately translucent, like a memory of the celluloid that had once been the basis of photography. (Remember all of those 35 mm. slides and their projection, which once mediated our experience of art as thoroughly as the internet and our monitoring screens do nowadays?)

Because they record a moment of actuality, of course, all photographs serve a memorial function. But memory is also a purpose of drawing; and the drawings that Graham photographs are crude and rudimentary “aides memoir,” jotted down as ideas came and went. However, since the drawings were made as plans for future projects that she was considering, the drawings actually looked forward in time. Looking closely, we can see a blocky sketch of a table with its legs roughed in; and in another drawing, a loopy scrawl that she calls a “cloud.” We see a cartoony wind-up key (A skate key? Or a can opener?). In several drawings there is an outlined box that she refers to as a “pencil box.”

But if a photograph is a means of holding onto an aspect of the past, of retaining a memory of what is slipping away, there’s also a poignant element of loss in these photographs and in the damaged drawings they hold, which are about to be disposed of and lost forever. The drawings feel all the more fleeting as the white light eats away at their edges. In the light’s glare, the drawing paper is transformed into a semitransparent and ghostly substance, like the shed skin of a cicada. And if, like the shell of a cicada, the photograph is the exact counterpart of the original, the drawings seem equally comparable to a shed cicada shell—having served their function, they’ve been discarded. Arrested before our eyes, they are abandoned ruins.

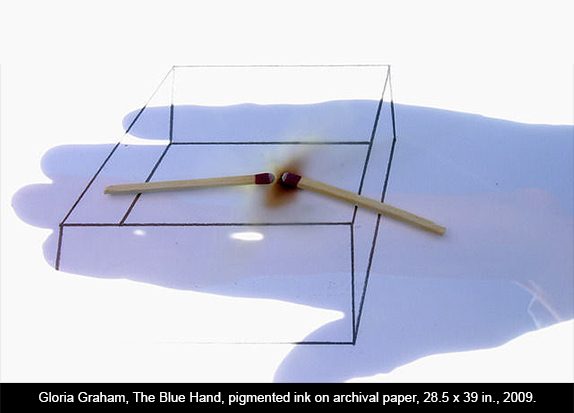

One of the proposed projects that Graham drew on these discarded pages evidently involved matches, since outline sketches of matchsticks occur frequently among these images. In one case, the drawn matches coincide with tiny burn spots, where actual matches were apparently dropped onto the original paper and left little scorch marks as their flames extinguished.

There’s also a pair of matches in a photograph of the cool blue shadow of Graham’s hand, which hovers over a simple line drawing of a box. In the center of the drawing is the smudge of a scorch mark and two (actual) unlit matches rest atop it, meeting at the point where the middle fingers join the palm in the hand’s shadow. Immediately the sensation of pain is invoked. It seems that somebody is about to get burned. We might think of a child playing dangerously with matches—or perhaps of Kirk Douglas’s fiercely melodramatic Vincent van Gogh, holding his hand over a candle flame to prove his desperate need of love and his imperviousness to the cost of his determined devotion. In any case, we cannot fail to respond to that conjunction of a hand and the potential of fire. (And does it matter that the two matches that it will take to make a flame are boxed in and about to flare at the point of the ring finger? Is a marital conflagration implied?) With such simple economy of means, Graham produces extravagant visual poetry.

A memory of fire—as an ethereal smoky residue—was a longtime feature of Graham’s ceramic art. In the 1970s and 1980s Graham was one of the premier ceramic artists of New Mexico. Along with their grace and refinement, her ceramic pots and other clay forms often featured blackened, charcoal-like smudges where bits of copper wire or small metal plates had been affixed to the clay surfaces and were vaporized in the fiery heat of the kiln, leaving only a ghostlike burn mark in their place. These darkened discolorations were a reminder of the object’s subjection to fire in the kiln. But they also enhanced the archeological character of her ceramics, lending them a quality of having survived the damage of time, as if they had come down to us from some distant culture of the past. Was it a culture that perished under the torch of an invader, or was it scorched and buried by a volcanic eruption? The origins of Graham’s ceramic objects seemed, in any case, obscure and inconceivably remote. But they provoked a profound meditation on the nature of time and endurance, which continues in her recent photographic works.

During the years when she was working at ceramics, from the late 1960s through the 1980s, Gloria and her husband Allan Graham lived in an old motel complex on North Fourth Street, which dated back to the days when Route 66 doglegged up in that direction. They transformed the old adobe units of the motor court into a series of living spaces, studios, and exhibition spaces, and rented out some of these to other artists. They also ran the Motel Gallery in one of the units. It was there, in the early 1970s, that I first saw the work of Terry Conway, Richard Hogan, Dick and Bill Masterson, and Bruce Lowney—artists who became leading figures on the contemporary art scene of New Mexico.

Ducks and beautiful guinea hens wandered the premises and a koi pond with its serenely jewel-like fish graced one courtyard. At some point, Allan and their son Jess dug a kiva for meditation and retreat on the property. As the local toads also found it a convenient place to chill out, the kiva came to be called the Toadhouse. Allan would later take the name Toadhouse for a certain aspect of his art, somewhat in the spirit of the ancient Chinese poets, like Han Shan or Cold Mountain, or in the manner of Duchamp’s Rrose Selavy.

Poetry, art, and music had the run of the place. I remember that it was there that I first heard a recording of Einstein on the Beach, long before Koyaniska’atsi, and before very many people in New Mexico had even heard of Philip Glass. The Grahams continued to push artistic boundaries in their art. They went on to become significant players on the international art scene, with Count Guiseppi Panza and Emily Fischer Landau among their devoted collectors. They also moved from the Albuquerque motel complex to a remote area of Northern New Mexico, reached only by a boulder-strewn dirt road. But they would continue to maintain ties to Santa Fe, both having been featured at SITE, and showing over the years with Linda Durham, and then James Kelly, and now with the David Richard Gallery.

Many years ago, in an attempt to address the mysterious effect of time in Graham’s ceramic works, I called on the words of the great art historian, George Kubler (1912 – 1996), found in his masterpiece, The Shape of Time. It was a question of the difficult existential realization of one’s entrapment in time, a feeling of isolation that Dickenson caught to her dismay in the slant of light—a “heavenly hurt” that left “no scar / but internal difference / where the meanings are.” “Why should actuality forever escape our grasp?” Kubler asked:

“The moment of actuality slips too fast by the slow, coarse net of our senses. The galaxy whose light I see now may have ceased to exist millennia ago, and by the same token men cannot fully sense any event until after it has happened, until it is history, until it is the dust and ash of that cosmic storm which we call the present, and which perpetually rages throughout creation.”

Kubler was a Yale scholar who published his dissertation on The Religious Architecture of New Mexico in 1940 and went on to become not only a leading historian of Spanish Colonial art and architecture, but also one of the first great scholars of Pre-Columbian art. It was within his study of early Native American civilizations, where there was no written language to serve as a guide, that Kubler grappled with the problem of time in human affairs and developed his theories about tracing its patterns. He discovered the “shape of time” in the transformation of art forms from generation to generation and in the borrowings between neighboring cultural traditions as objects were traded, copied, and modified during their dissemination.

In describing this process of change, Kubler’s words feel particularly relevant to the way that Graham’s photographs of her fated drawings can carry meaning for us:

“Now and in the past, most of the time the majority of people live by borrowed ideas and upon traditional accumulations, yet at every moment the fabric is being undone and a new one is woven to replace the old, while from time to time the whole pattern shakes and quivers, settling into new shapes and figures. These processes of change are all mysterious uncharted regions where the traveler soon loses directions and stumbles into darkness. The clues to guide us are very few indeed: perhaps the jottings and sketches of architects and artists, put down in the heat of imagining a form, or the manuscript brouillons [scratchpads] of poets and musicians, crisscrossed with erasures and corrections, are the hazy coastlines of this dark continent of the ‘now,’ where the impress of the future is received by the past.”

Gloria Graham’s photographs are currently on view through May 24 at the David Richard Gallery in Santa Fe’s Railyard District. A sampling of the artwork can also be found on the gallery’s website at www.davidrichardgallery.com. Another source with an in-depth look at Graham’s work in a variety of media is her studio website: www.gloriagraham.info.

Responses to “Gloria Graham: A Certain Slant of Light”