Museums are special places. Sometimes they invite one into spaces where art and history are presented beautifully, but removed from context.

In recent years, there has been a tendency among museographers to add this missing context—for example displaying paintings and other art objects accompanied by the furnishings of the era in which they were produced. Some countries have nurtured advanced concepts of presenting its riches: archeological, historical, or artistic. France comes to mind. Also Mexico. Others, such as Egypt and Peru, have extraordinary treasures, but tend to accumulate them in crowded spaces with dusty showcases.

Western colonialism has robbed many lands of their most precious findings and taken them away to exhibit in the great museums of Europe and the United States. Greece’s Elgin Marbles are only one of thousands of examples.

In recent years, there have been efforts to right this wrong. The Nazis, too, stole many important paintings belonging to the Jewish families they rounded up and murdered; descendants still fight to retrieve what is rightfully theirs.

Another great problem in many countries is the ongoing practice of grave robbing and the international traffic in treasure it has spawned. There has been some degree of success in bringing this situation to public consciousness and stopping—or at least reducing—the travesty.

Mexico has always had great museums. Long before the advent of the latest in museum technology, the country’s magnificent art and archeology were shown in ample spaces accompanied by decent descriptive signage. In the past decade, though, Mexico’s museography has received a shot in the arm. Innovative displays, suggestive display, multimedia videos, new interactive features, and a more accurate rendering of history can be found even in museums in the smaller cities and towns. Signage is frequently presented in Spanish, English, and the native tongue of the culture depicted. Often, the indigenous language is presented first.

Located within Chapultepec Park, Mexico City’s magnificent Museum of Anthropology and History, the country’s most visited, has 23 exhibition halls and occupies almost 20 acres. Although drawing on a wealth of pieces that had been collected for decades, it opened in its current location in 1964. It houses, among many other important pieces, the Aztec Calendar Stone and the great statue of Coautlique. An immense stone figure of the rain god Tlaloc stands just outside its doors. The museum’s architecture, with its grand patio and imposing fountain, provide the perfect backdrop to this history of pre-Columbian life and art. Most exciting, at any given time one observes peoples from the country’s many indigenous groups looking at their own past; often their features mirror those of the mannequins at which they gaze.

Behind the Zocalo, Mexico City’s great central plaza, a museum was opened in 1991 to house and present the treasures emerging daily from the Templo Mayor dig: the great pyramid of Tenochtitlán destroyed by the Spaniards and replaced by a Catholic cathedral. This museum is the place where finds are made available to the public.

These are but two of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Mexican museums—some decades old, others having opened their doors during the country’s artistic renovation over the past several decades. Curating is an important discipline in Mexico. On a recent trip, I was invited to speak to a group of doctoral students in the discipline. They employ their creativity to better explain our past, present, and future. Their ideas remain powerfully with me.

On that trip, I also visited a number of museums. Some, like Frida Kahlo’s Blue House in Coyoacan, had undergone great changes since the last time I’d been there. Parts of the convent where Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz lived and wrote have been renovated and are open to the public by appointment. At this convent, an innovative multimedia video proved very effective in transmitting Sor Juana’s life. This videography is increasingly being used in other Mexican museums.

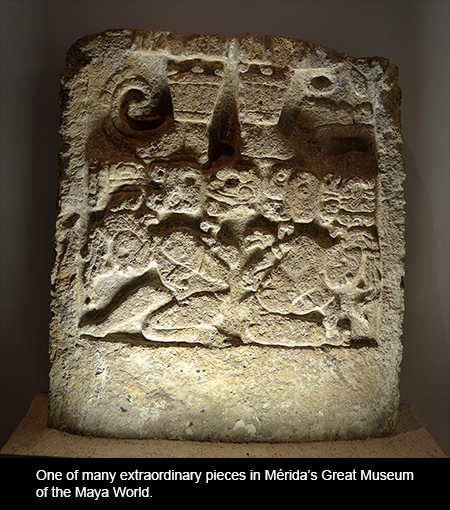

On an even more recent visit to the country, this time to Yucatán, we spent several worthwhile hours at a two-year-old museum called El Gran Museo del Mundo Maya de Mérida (Mérida’s Great Museum of the Maya World). It opened in December 2012. Covering several city blocks, the modern building houses research labs as well as two main exhibits.

The first presents the meteorite that smashed into earth some 65 million years ago, putting an end to the era of the dinosaurs and lifting the Yucatán peninsula out of the ocean to eventually become home to the Maya. The second displays Maya geography, history, culture, language, art and architecture, food, clothing and customs. It begins in the present day, moves back in time, then forward again. The curating is stunningly beautiful, with legends in Maya; Spanish and English, many outstanding pieces presented in very original ways, and a dozen or so of these new videos explaining one or another aspect of the complex Maya cosmography. One of these, for example, depicts what human bones tell us about the people when they lived. I thought of the extraordinary video we had seen at Sor Juana’s convent, and couldn’t help wondering if Mexico is ahead of the U.S. in this medium.

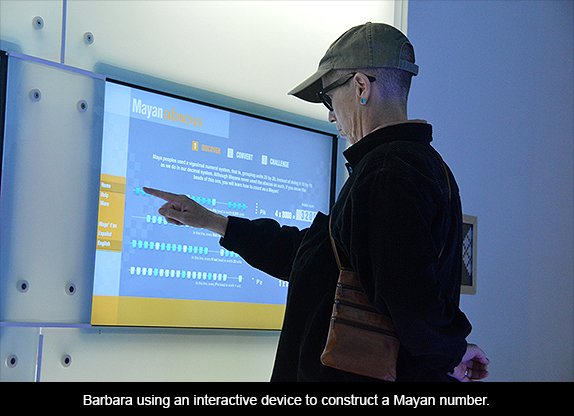

On an interactive digital abacus, my partner Barbara tried to construct a Mayan number. Translating the “beads” to Mayan dots and dashes, in a number system based on 20, was absorbing and challenging. A large facsimile of the Paris Codex made me realize there’s a direct line between the codex’ pictorial content and some of Barbara’s artwork: a particular pictographic language and a sort of tendency toward cartooning. Guides and other museum staff were all especially nice, never simply indicating where to go, but accompanying us from one exhibition site to another.

In one part of the museum, a group of elementary school kids were there in uniform with their teachers. Viewing one of the videos that had to do with the Spanish conquest, one of the young girls suddenly stood up and exclaimed: “That’s my name! That’s me!” She seemed both astonished and concerned. One of her teachers very gently sat down beside her, talking to her in quiet reassuring tones. The visit dealt intense emotion as well as an excellent informational experience. This museum is said to be the most important in Mexico devoted to the Maya.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Yucatán V: Mérida’s Great Museum of the Maya World”