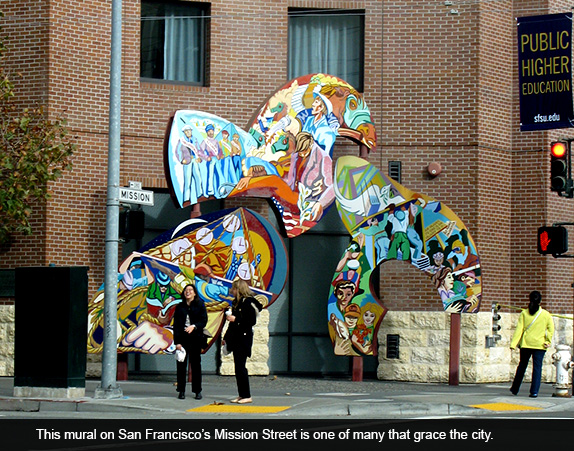

Here in Albuquerque we have a growing number of examples of great public art. In an earlier piece, I wrote about some of them. I recently returned from a week in San Francisco, one of the US American cities with truly spectacular murals and other types of well-executed and meaningful creative ambience. To my mind two things make San Francisco’s street art so exciting: the talent of the city’s artists and a tradition that has grown out of decades of community activism.

Hundreds of murals, often painted by collectives of artists working together, can be seen throughout the Bay Area. They began to appear in the 1970s as an integral part of a variety of people’s struggles being waged at the time. The Chicano Mural movement was important in this history. The San Francisco murals were linked to other mural manifestations—most notably in places like Los Angeles, Minneapolis, and New York—and, as is true of all art movements, continued to grow and change to embrace elaborate street graffiti (stylized writing as symbolic design), political signage, gang tagging, and the work of exceptional individuals such as Keith Haring and the ineffable Bansky. Hip Hop culture gave free rein to a popular expression almost always meant to counter the overly neat and clean (and deceitful) power of commercial visual coercion.

The San Francisco murals generally embody empowering sociopolitical messages. But they are neither the haphazard work of street artists nor the rapid-fire products of middle-of-the-night effort. The important ones were painted by established artists who have studied and experimented with the qualities of paint and binders that may enjoy a long wall life. Like the great Mexican muralists of the early-to-mid-twentieth century (Rivera, Siqueiros, Orozco, etc.), they make visual statements for the ages. In this appreciation I will refer to three I find particularly magical.

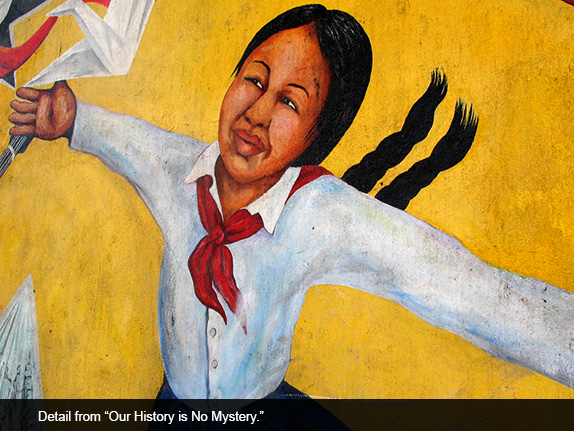

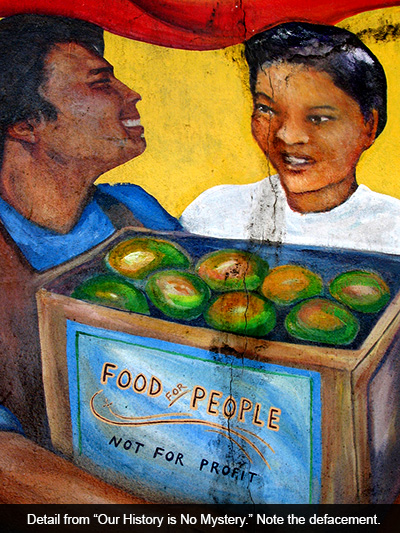

The first is “Our History is No Mystery,” the two-block long mural that covers the retaining wall of the City College of San Francisco’s John Adams Campus at the corner of Hayes and Masonic. I won’t spend much time on this early example of the city’s mural movement, because interested readers can refer to “Two Murals Reach Across Time,” a piece I devoted to it and to a 200-foot long panel of Ancestral Puebloan rock painting at the Great Gallery in Horseshoe Canyon, Utah.

As I almost always do when I visit San Francisco, though, I made my pilgrimage to this example of mural art reminiscent of the beginning of the area’s wall art movement. It was originally painted in 1976 by the Haight-Ashbury Muralists collective, and reads as a school history lesson from the viewpoint of working people. Here you will find vibrant images of the city’s Black, Brown, and Asian legacies, countering the whitewashed “history” too often found in school texts and featured on what passes for mainstream news. “Our History is No Mystery” frequently suffers damage by those who, for whatever reason, feel they have a right to deface it. Such damage, as well as weathering and dirt, could be seen when I was there. The muralists undertook a full-scale restoration in 1995, aided by John Adams students and staff. Periodic work will continue to be needed from time to time in order to maintain this historic treasure.

Unique among the San Francisco murals is the one covering two facades of The Women’s Building at 3543 18th Street in the Mission. The building itself dates from 1910 and tells the story of San Francisco’s rich cultural layers. It was a German gym and Norwegian hall before becoming the first women-owned and operated community center in the United States in 1979. It houses the offices of a number of community organizations, a large performance space, and offers a variety of services to women. Painting space on the building is disconnected, oddly shaped, and required enormous creativity to become the mural it is today.

The building, which is also a mural, or mural that is also a building, attracts sightseers from around the world. They raise their cameras from across the narrow street to try to frame its visual story, then move closer to photograph the brilliant details of “MaestraPeace,” painted in 1994. The art on this building is a symbol of women’s contributions throughout history and from around the world. Dominating is a large image of Guatemalan indigenous freedom fighter Rigoberta Menchú. The Chinese Goddess of Mercy Quan Yin is there, Yemeyah and Coyolxauqui can be seen, and women farmworkers and union leaders as well as local female personalities, Georgia O’Keefe, and Audre Lorde are featured, among ribbons embossed in beautiful calligraphic script that carry other women’s names in and around the central portraits.

Over the years, this mural like others around the city, suffered damage and needed renovation. One of the muralists, who is a friend, gave me a copy of a small book that describes the 2012 process of restoration. Its initial paragraph perfectly conveys the feel of that project:

Summer 2012. For the first time since 1994, Juana Alicia, Miranda Bergman, Edythe Boone, Susan Cervantes, and Meera Desai, climbed the five-story high scaffolding to inspect their MaestraPeace Mural. High over the Mission District, their fingers touched the images as they got reacquainted with their magnificent accomplishment and made a long list of restoration work that needed to be done.

The building’s drainage gutters, balconies, window frames and general façade all needed work. And so the project became one in which the art and the structure that displays it were brought up to code at the same time. The original artists worked with carpenters and plumbers, as well as the structural experts who are always consulted in this earthquake prone location. Hundreds of community people and others for whom the building is an important landmark contributed financially to its restoration.

The third mural I want to feature is the most interesting to me, as well as the most diverse and intimate. It is actually a series of different frames, each painted by an individual artist or team. This is Balmy Alley, between Harrison and Treat Avenues and 24th and Streets in San Francisco’s Mission District.

In 1984, thousands of Central American refugees, escaping their countries’ murderous dictatorships, flowed across the southern border of the United States seeking safety from the ravages of war. Many came to the San Francisco Bay Area, where they were embraced by the area’s Spanish-speaking Hispanic and working class communities. An artists’ project that called itself PLACA wanted to record this history in images.

They chose this alley, previously home to drug dealers and their impoverished targets, to make their statement in paint. Back fences and makeshift garage doors—some of wood, others metal—lined the sad space. The artists had to ask permission from every property owner; only a few refused. They got a small grant, really only enough for their materials, and the painting began. Each artist had his or her own vision and so each mural was different. All spoke to the issues of the 1980s: immigration, jobs, education, freedom of expression. Photographs of people in El Salvador or Nicaragua often served as reference points for the faces on the walls. Longtime residents as well as frightened newcomers spent hours watching or helping with the creation of these murals; the process undoubtedly made the latter feel they had found a new home.

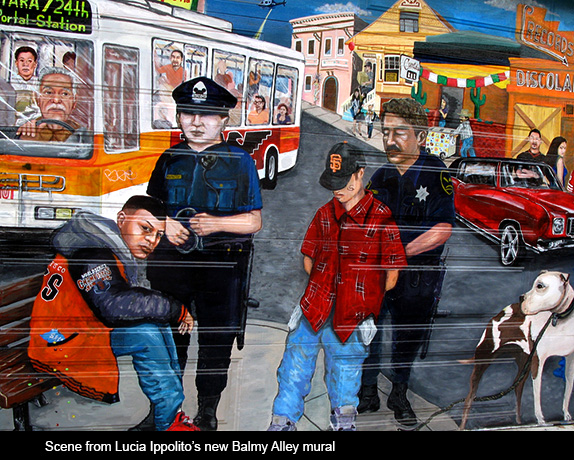

Over the next 25 years or so, many of the Balmy Alley murals faded or chipped. A few of the landlords no longer wanted the artwork on their property and tore down the boards or metal backs. New issues also emerged: Hurricane Katrina, intolerance and street violence, police brutality, gentrification, hard times for working people, and—always—the unfinished business of immigration. Just this year, some of the original artists and a few new ones decided to raise money to repaint. Some images changed with the times. Others remain.

On this visit two brand new Balmy Alley murals caught my attention. Side by side, they are by Lucia Ippolito, a second-generation painter. Beautifully rendered artistically, they are no less exciting in terms of content. They allude to the current push for neighborhood gentrification, in which rents are being raised dramatically, the old mom and pop business are being pushed out, and upscale cafes with their $15 lates are moving in.

The theme of this new mural is "Aquí estamos y no nos movemos" (We’re here and we’re staying). In one frame two policemen have rounded up two young neighborhood men (Skittles are spilling out of the pocket of one, in clear tribute to Trayvon Martin). A street sign reads UAN WEY, another OTRO WEY. An overly-dressed white woman promenades her manicured dog. Humor adds to the richness of the images. It’s wonderful to see younger artists taking over where their elders left off.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: When Art Inhabits the City - Part 2”