It was one of those cold bleak days announcing that, although winter is still officially weeks away it may be a crude one this year. Even the proverbial New Mexico light was dulled beneath a blanket of low leaden clouds. We drove east on Interstate I-40 just past Cline’s Corners, where we turned north on State Highway #3. Flat pale colored grazing lands, their creamy carpet always appearing softer than it is, began to be dotted by Juniper and Cholla, the latter’s arms frozen in grotesque gestures. The land itself began to undulate, and then break up into hills and valleys. As we navigated the narrow twisting pavement, we noticed that the car’s outside thermometer read 21 degrees.

We were headed to Villanueva, a small Hispanic village nestled just where the Pecos River winds through a narrow valley south of Las Vegas and Santa Fe. As the road descended its final tight turns to the valley floor, the glistening surface of rushing water reflected a last bloom of fall leaves in tones of reddish brown and dull gold. Seen from this high approach, Villanueva looks picture perfect.

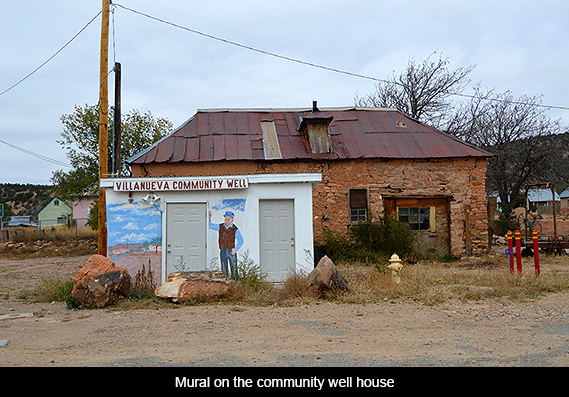

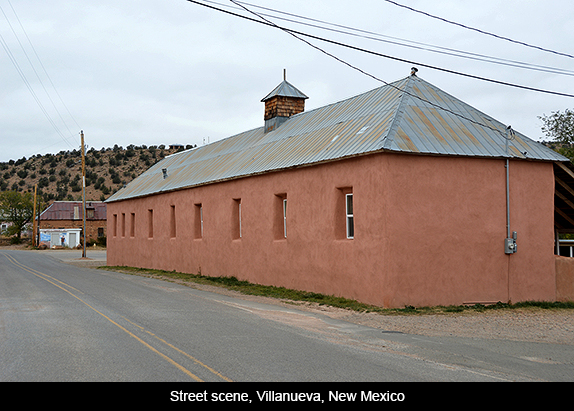

Entering the village does little to diminish this impression of lovely old adobes built at irregular angles along a few meandering streets. Some have new tin roofs, others have gone to ruin—no doubt victims of an economy that has affected every part of the state and nation. But Villanueva projects a settled feeling, an aura of everything being in its place. There is a sense of peace alongside obvious hardship.

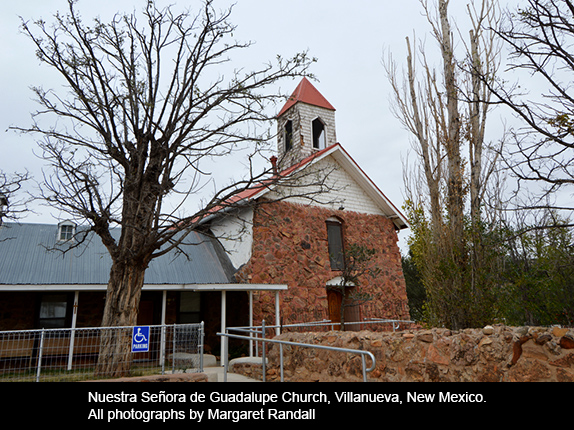

The stone church that was our destination is right across the way from the general store, where the warmth of those behind the counter matched the physical warmth we experienced coming in from the cold. Fresh coffee had just been brewed. I asked the man who announced its readiness where we might find someone willing to open the church.

We had come to see the 265-foot long colcha, or tapestry, displayed on the inner walls of that church. “You want to see Mallie,” the man said, “just go around to the side door and knock. You’ll find her in the church office.”

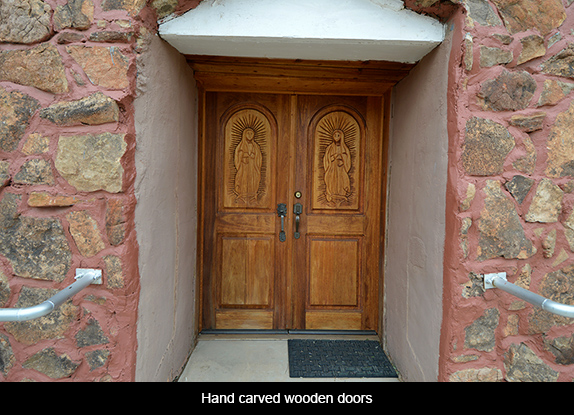

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe Church probably doesn’t look much different from how it appeared when it was completed in 1830. It is constructed of the same rough stones used in several other local houses and barns, with a cupola of white shingles topped by a slender wooden bell tower and simple cross. The double front doors of unpainted wood are roughly but masterfully carved.

Mallie immediately invited us in from the frigid outside air. She gave us a small informative pamphlet with basic information about the village, the church, and its tapestry. Villanueva was founded in 1790 as La Questa, but at some point, early in its history, a new neighborhood became known as Villanueva. Some say the name was because of its add-on nature; others that it referred to a prominent family. In any case, it is the name by which the village is known today. Mallie picked up her ring of keys and led us briefly outdoors again and into the body of the church.

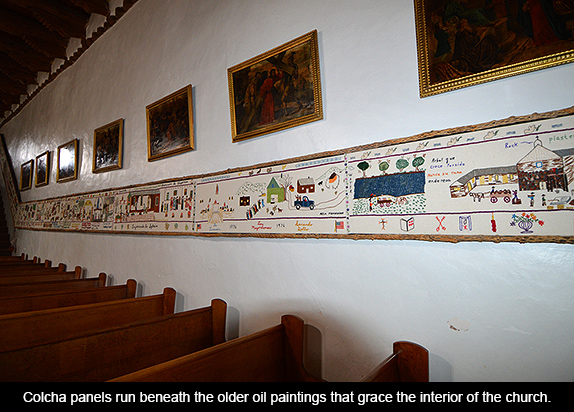

The visitor’s first impression is one of pride and loving upkeep. Villanueva shares a priest with the nearby village of San Miguel, and mass is celebrated not only on Sundays but on several weekday mornings as well. Two rows of hand-hewn wooden pews fill the narrow nave. Mallie turned on the lights, and the altar with its prominent backdrop of Our Lady of Guadalupe was immediately bathed in a soft glow. The church’s inner walls are immaculately white. Dark oil paintings line those walls, and just below them, in a continuous line that runs along both sides, through the altar area and even up into the choir loft, is the famous colcha or tapestry.

According to Suzanne P. Macaulay, in Stitching Rites: Colcha Embroidery Along the Northern Rio Grande (University of Arizona Press, 2000), Villanueva’s tapestry, although linked to the tradition of hand-stitched colchas of the San Luis Valley of southern Colorado, also differs in important ways. The latter are embroidered by individuals. The village was “the scene of an exemplary stitching project created during the later colcha revival period of the mid 1970s,” the product of which is this amazing narrative on cloth.

In that decade, Macaulay writes, Santa Fe’s Museum of International Folk Art, under the leadership of its director Yvonne Lange and Chilean artist-stitcher Carmen Benavente de Orrego-Salas, targeted several area communities for the possible establishment of embroidery workshops. They posted notices around the northern part of the state, in such places as Abiquiu, Pecos, Villanueva, Mora, Rainsville, and Guadalupita, hoping to recruit women who wanted to stitch. They promoted the concept of embroidery as pictorial narrative and stressed the use of everyday experience as a source of creative design. They posted their notices in Spanish as well as English, and hoped to draw on a lapsed craft tradition as well as stimulate local economies if the idea caught on.

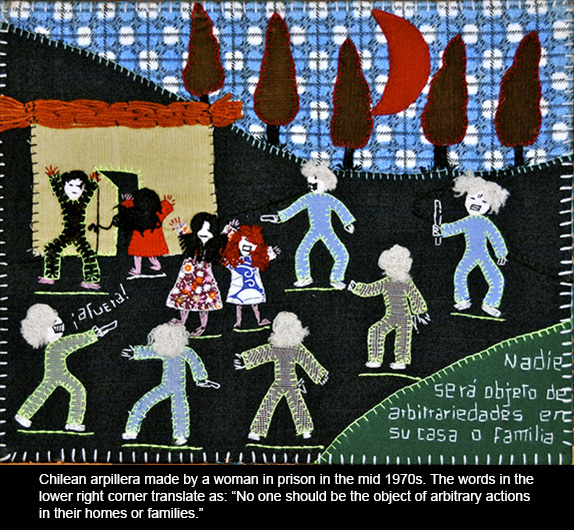

In Villanueva, Lange and Benavente de Orrego-Salas hit a goldmine of collective spirit. Benavente de Orrego-Salas, although living in the US was born in Chile, a country that has its own rich history of fabric art. During the Pinochet dictatorship, when many women were relegated to concentration camps, an explosion of arpilleras emerged from their brutalized but talented and courageous hands. These pictorial squares, stitched with whatever bits and pieces of cloth and yarn the women could obtain, depicted scenes of pathos and hope. They made their way around the world, telling stories of struggle and raising money for the resistance.

In 1971 Benavente de Orrego-Salas traveled to her native Chile, to the village of Ninhue near where she was born. There she started a workshop based on crewel embroidery techniques she had taught herself a decade earlier. As Macaulay writes: “Her enthusiasm and her belief that authentic art must come from one’s heart and life have endeared her to workshop participants ever since.”

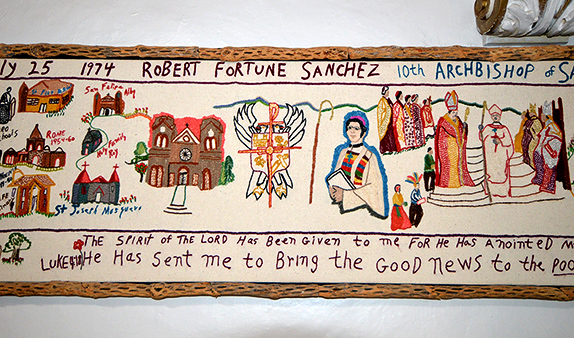

The women of Villanueva took to the workshop idea, bringing their own energy and creativity. The idea for the collaborative enterprise came from Father Louis Hasenfuss, of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe Church. The concept, as well as the enthusiasm of the original 11 women who eventually grew to 36, set the endeavor apart. Lange and Benavente de Orrego-Salas decided to take the idea on as a bicentennial project. They would supervise the creation of a tapestry that encompasses the history, folkways, and religious life of their community. The result is this string of 41 panels, making a pictorial narrative of Spanish exploration and occupation of a particular site in the Southwest from 1625 to 1976. It blends the larger historic events with more intimate panels showing a wedding or other village happening.

The Villanueva tapestry is a monument to cooperation and enduring sisterhood. As one of the stitchers, Isadora Madrid de Flores, says: “Nobody knew about art . . . [But] we were a small village, where everyone knew each other. We were all Spanish, all Catholics, and mostly everybody is related.” The participants used the regional mobile library and also traveled to libraries in other towns to gather historical information. When confounded by drawing some of the more difficult figures of people and animals, or with problems of perspective, they sought help from family and friends, especially those of the younger generations. Grandmothers and grandchildren worked together.

Benavente de Orrego-Salas described the kind of self-discipline she felt was needed and advocated in order to be a more effective mentor and monitor of the tapestry’s artistic standards: “We needed to be brutal . . . to encourage and stress individual expressiveness by saying, ‘It is you (the work is you, the piece is you) because you are unique.’” Later she would add: “You have to be brutal with a lot of sense of humor.”

The tapestry at Villanueva is not really a tapestry in the traditional sense of that term. The panels, which are 21 inches high (except for those on the choir loft, which are 13 inches in height), are done in a variety of stitching techniques. The plain white cotton muslin is always background, and the embroidery is tighter in some scenes than in others. The names of those featured and/or events depicted are incorporated into the individual scenes. Many showcase religious celebrations. The entire stream of panels is beautifully stretched and framed, top and bottom, by an unobtrusive but visually pleasing bastion of dried and shellacked Cholla branches, typical of the cactus that dots the local landscape.

Immediately to the right as one faces the altar, the tapestry begins with the theme of Mother Earth, continues with Indian Paradise, and then follows the history of Spanish settlement all the way through to 1976. This big story is told in many smaller stories, each a part of Villanueva’s history of religious, cultural, and social life. The tapestry culminates in a scene of The Coming of Our Lady of Guadalupe, from the well-known story said to have taken place in a similar village far to the south, in what today is Mexico. A brown and compassionate Virgin appeared to a poor peasant named Juan de Diego. Our Lady of Guadalupe, then, differentiated herself from the whiter, more austere, upper class Virgins prevalent in Spain. Poor Mexicans needed a Mother who understood their lives and needs, just as the people of Villanueva need one who speaks to them.

In preparation for upcoming Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe festivities, there was a packet of postcards on the church office’s desk, one of the many painted images of this particular Virgin, with a prayer printed on the back. The prayer read, in part: “Merciful Mother, you came to tell us of your compassion through Saint Juan Diego, who you called the smallest and most beloved of your children. Imbue with your strength and protection all those who live in poverty, especially the young, the elderly and the vulnerable . . . so that all those who work for justice and for the poor may feel Divine Love in their daily lives in tangible ways . . . “

Mallie told us that Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe parish is made up of about 230 families. Research reveals that the 2000 census registered only 267 people in the community. 83.4% of them listed themselves as Hispanic. The village’s 7% unemployment rate is slightly lower than that for the state as a whole, probably reflecting the fact that even those involved in rudimentary or part time work consider themselves as having jobs. Most of Villanueva’s men go to Las Vegas or Santa Fe to work, many of them in construction or waste management. Others farm, hunt, and fish locally. The 2012 census shows a $16,000 per capita income. The area is overwhelmingly Democratic, 70% of the community having voted for Obama in the last presidential election.

The Villanueva tapestry is a rich and unique example of rural fabric art with deep roots in the community. It is well worth a visit. Villanueva State Park, with its red rock landscape is just a mile and a half outside town and, whether you arrive from the south or from the north, the approach to the village is breathtaking. Although we drove to this magical valley as winter settled through its hills, spring and summer are probably the best times to go. Then the fertile surrounding farmlands must truly come alive.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Villanueva’s ‘Colcha’ Tapestry”