I say Uruguay, and someone invariably asks: “Paraguay?” A few vaguely know it’s one of those countries with an ay sound way down there at the tip of South America. A tiny nation stuck between much larger Argentina and Brazil, Uruguay was invented by Lord John Ponsonby, the same man who created Belgium and for the same reason. In Europe, France and Germany were having border issues; it seemed like a good idea to devise a buffer country between them. The project was so successful it was repeated a few years later in Latin America, and Uruguay gained its independence with the Treaty of Montevideo in August 1828.

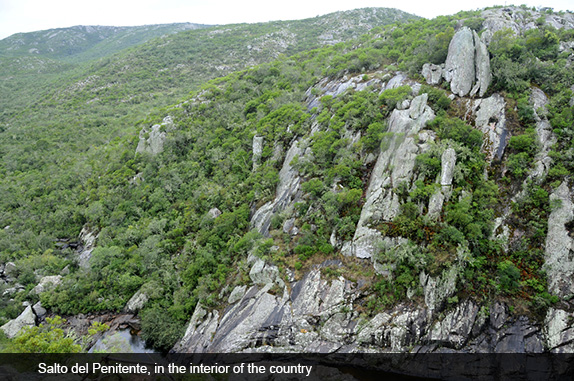

I know about Uruguay because my son and his family live there. My partner and I visit almost every year. It is not beautiful in the way of Mexico or Guatemala or our own United States, with their dramatic varieties of landscape. Except for its remote interior, Uruguay is mostly flat, known for its beaches stretching out in both directions from the capital city of Montevideo along the broad La Plata River. I’m not fond of beaches.

What Uruguay has is its people—warm, politically sophisticated and culturally rich—and its proud history of resistance. This resistance had an early incarnation in José Gervasio Artigas, the revered liberator who roused a gaucho army in the early 19th century to fight against monarchy and for federalist principles. Artigas promoted enlightenment in many areas, including women’s rights. His feats served as an example to later revolutionaries, like the highly creative Tupamaros who fought a string of dictatorships in the country during the 1970s and ‘80s.

Few in the U.S. remember the brutal dictatorships that victimized Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Brazil throughout the 1970s; nor to what extent those countries’ paramilitary forces worked across borders to join forces in capturing those who opposed them. Yet thousands were tortured and killed, and tens of thousands disappeared—that quintessentially Latin American deathblow in which mostly young people were taken from their homes, workplaces or the streets and never seen again. Thirty thousand in Argentina alone. An entire generation. The model was meant to instill terror in whole communities. News of those “dirty wars” didn’t often appear in our mainstream press. U.S. administrations at the time supported the regimes in question.

I lived in Latin America then, so I knew about those regimes and also about those who so heroically opposed them. In Cuba, in 1983, my son married a Uruguayan woman, Laura. She and her sister and father had been forced into exile and, like so many others, had been welcomed by the Cuban revolution. Her father had been the dean of the school of medicine at Uruguay’s University of the Republic. When the dictatorship fell, in 1985, and when he was able to go home, ten thousand students met him at the airport. Most of them hadn’t reached their teenage years when he’d had to leave. But in a nation of only three million, collective memory runs deep.

It may be Uruguay’s small size that has made its extraordinary recent history possible. Almost every family has members on both sides of the political divide. In my daughter-in-law’s family an Italian anarchist grandfather represented the best traditions of the ongoing struggle for justice, while his brother was a general during the dictatorship and undoubtedly responsible for repression against a number of younger family members. Both men are long gone. Happily, the former’s legacy prevails.

Among those in the family’s next couple of generations there were several freedom fighters; Laura’s aunt Gingi was a Tupamaro who spent more than a decade in prison, later became a doctor, and is still active on behalf of the families of the disappeared who continue to search for their children’s bodies and for the whereabouts of grandchildren who were often stolen from assassinated parents and adopted out to military families.

Memory is important in Uruguay, as it is everywhere such horror has been unleashed. When that horror is defeated, there are differences of opinion about how to keep the collective memory alive. In Uruguay, as I say, every family has its loss. In Montevideo, the Museum of Memory is housed in what was once a dictator’s mansion. Here the histories of repression, torture, murder, and disappearance have faces and first and last names. Above the city, in the working class neighborhood of El Cerro, a monument to the disappeared displays their names etched into large panels of glass in two rows set in a grassy park. Families picnic nearby. Some visit this evidence that their loved ones lived.

And memory, for individuals, sometimes follows a line of dark humor. I’ll never forget Gingi taking us to Punta Carretas shopping center one day. The mall’s main façade has a crenelated roofline, reminiscent of its prior occupancy. This was once a military installation. Inside, Gingi pointed to a small shop and said: “That’s the cell where I was tortured. Now I buy my bras there.” Perhaps humor is an outlet for pain.

A people with this sort of history is not easily swayed by deceptive political rhetoric. In Uruguay, voting is obligatory. Citizens living abroad even travel home to take part in national elections. This led to the astonishing outcome of a referendum that took place in 1980, in the middle of the dictatorship. The issue on the ballot was a modification of the Constitution the dictatorship proposed. The yes box was the only one a person could check, but more than 57% wrote in the world “no.” This overwhelming demonstration of repudiation provoked the end of the regime, which fell three years later. This event was particularly noteworthy given the fact that the laws against assembly and organization were so stringent at the time. There was even a series of words that were proscribed, words such as Tupamaro and freedom.

What followed after the dictatorship ended was a series of quasi-democratic administrations. The times had changed, and even the United States was no longer eager to support the brutal Latin American regimes it had propped up for decades. In Chile, Argentina, and Uruguay the military governments were out.

Uruguay’s two traditional political parties, the Blancos and the Colorados, were no longer perceived as reflecting the aspirations of a decimated citizenry. Issues such as assigning responsibility to torturers, amnesty or indemnity for those who had caused such pain, and indemnification for those who had been victimized, were on the table. Political forces aligned and realigned. And then an array of left parties and organizations formed a broad front, the Frente Amplio.

The Frente Amplio’s first presidential victory came with Tabaré Vázquez, an oncologist who governed from 2005 to 2010. Vázquez presided over important improvements in education and working conditions, a significant expansion of the welfare system, and a dramatic reduction in poverty, with the percentage of poor Uruguayans falling from 32% to 20% of the population. But people felt he could have done more.

The Frente Amplio’s next candidate for president, and the man now at the helm, is José Mujica, popularly known as Pepe. He’s worth describing in some detail. It would be hard to imagine such a person as president of the United States.

In 1972, with the Tupamaros all but defeated, the dictatorship held 11 of their leaders in abysmal prison conditions. They became known as the hostages, because the regime made it clear it would execute one each time the revolutionaries launched another armed action. The hostages endured most of their imprisonment in solitary confinement, one literally in a hole in the ground. Their grotesque situation lasted for 13 years. One of these men was Mujica.

When the dictatorship fell, most of the hostages either tried to reinvigorate the clandestine organization or were forced to attend to their own devastated health. Mujica decided to try operating within the system. He was a working class man who as a child had helped his mother sell roses at a city market. He had never gone to college, but was a voracious student in a variety of disciplines. He ran for Congress and won, arriving at work each day on his battered motor scooter. There’s a story about him parking the scooter in the congressional lot one day and a guard approaching to tell him he couldn’t leave it there: “How long do you plan to stay?” the man asked. “I hope another five years,” Mujica answered. There are many such stories.

Before Mujica was elected president of Uruguay, by an overwhelming majority, he spent 20 years in his country’s legislature and a term as Secretary of Agriculture. All of this provided invaluable experience, but couldn’t have prepared him for the job ahead. He assumed the presidency at a time when progressive governments throughout Latin America were on the ascent. Hugo Chávez was still alive in Venezuela. Evo Morales was Bolivia’s first indigenous president. Argentina, Brazil, Ecuador and Chile all had left of center administrations.

Among Mujica’s first moves were raising teacher’s salaries two and a half times, and health workers—doctors, nurses, and technicians—three. During his presidency, the University of the Republic, the country’s only public university that existed only in the capital city and had close to 100,000 students, began branching out. Campuses have opened in a number of states, each a first-rate center of higher learning and each reflecting that state’s needs. Uruguay is the only country in the world so far to have completely implemented the “one laptop per child” initiative, through which all students have been given their own solar-powered computer. Education is free through university. Health care is essentially universal.

Mujica does not live in the presidential palace, but has preferred to stay in his childhood home. Only his position has forced him to wear a suit and tie, and employ a chauffer and armed guards. He takes a portion of the presidential salary, returning the rest to projects benefitting the population at large.

Mujica’s government launched a number of programs designed to lift people out of poverty. Some of these have been amazingly successful. Of course there are problems, lots of them. Neo-liberalism’s encroachment on the continent has not spared Uruguay, and relationships with other countries and with the United States can be complicated. But just this year Uruguay has been able to pass two more pieces of cutting-edge legislation: its Marriage Equality Act, which legalizes all couples, gay or straight, and includes adoption and other rights. It is the first such law in Latin America. And after a long drawn-out struggle by feminists and others, abortion was finally decriminalized.

So, aside from visiting my family, Uruguay’s rational approach to basic human rights is definitely one of the reasons I love spending time there. People seem somewhat heterogeneous, but that may be misleading. Although it is commonly believed that the indigenous population was eradicated long ago, recent research shows that indigenous genes are alive and well. The Europeans who settled the tierras orientales were often Italians, German Jews, and even a few Germans of Nazi persuasion.

Uruguayans ferociously support their favorite soccer teams, celebrate special occasions with asados—barbecues at which the preparation of the parts of the steer follows a complex ritual (Along with Argentineans, Uruguayans consume more meat per capita than anyone else in the world)—and almost everyone sips mate.

This latter custom is one of the things that makes Uruguay Uruguay. Argentineans drink mate as well, but those from both countries are quick to tell you the other’s tradition is less than authentic. Mate is a bitter herb that is placed in a gourd about the size of an adult’s closed fist. Hot water is carried in a thermos, and poured into the mate at intervals to produce a strong addictive tea. This tea is drunk through a silver straw called a bombilla. One commonly sees people on the street, walking along with their thermos under one arm and the mate (the gourd is also called a mate) in the other hand. The most congenial part of the custom is how it is shared: friends and even strangers pass the mate around, creating a casual feeling of community. From the age of ten, my grandchildren have sipped the drink.

Uruguayans are a highly cultured people, who love art, music, theater, and literature. Mario Benedetti and Idea Vilariño were two of the twentieth century’s greatest Spanish language poets. Eduardo Galeano is one of its most brilliant writers. Musicians of the caliber of singer/songwriter Alfred Zitarrosa are wildly popular, and Daniel Viglietti keeps the musical tradition alive. Joaquín Torres García and José Gurvich are among Uruguay’s many extraordinary visual artists. I especially love Gurvich’s work. Again, more than the wealth of artists in the different genres, what strikes me about the country is how deeply its people enjoy artistic expression. Even popular manifestations, such as the neighborhood murgas that take to the streets during Carnival each year, are original operatic displays of political and cultural humor.

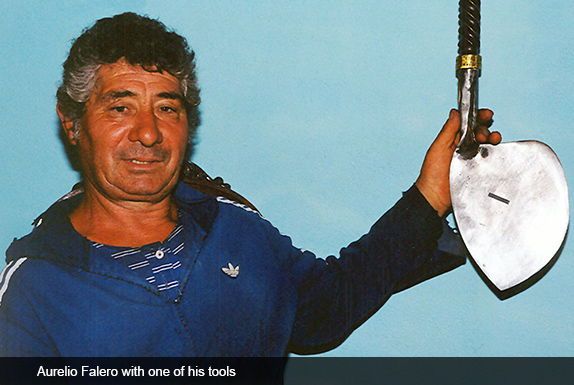

In Montevideo’s huge Sunday flea market we came across a man named Aurelio Falero. He was sitting at a table loaded down with tools, amazing tools. Falero finds the axe- and hammer-heads in junk yards, then fashions new handles for them from fine native woods. A mark of his genius is each handle’s perfect balance; you know just where to grab it to wield it correctly. We were fascinated by this man’s work. He seemed delighted to converse, and his invitation to visit him sometime in the small village where he lived seemed sincere.

One day, several years later, my son and I decided to try to find Falero’s house. We remembered the name of his village, and drove to it. As we approached we asked people we saw along the road if they knew where the artist lived. Everyone did. One after another, they sent us farther and farther from town, until we stopped at a small white washed house we knew must be his. Everything was very artistically pleasing: three sheep in a pasture, a vegetable garden, and one immense sunflower standing tall against the front wall. We were lucky. Falero and his wife were both at home. For the next couple of hours he showed us his workshop and the vast number of tools he had made. I wondered if there might be a market for them in the US, perhaps at a specialized gallery of some sort. Even though we knew doing so might help lift him from the life of struggle he so clearly endured, and although we ourselves purchased many of Falero’s tools, we never followed up on the idea of selling them here. Experience had shown us such schemes rarely come to much.

Throughout the country, there are many examples of popular artistic expression. One is a two-block string of houses in one of Montevideo’s outlaying neighborhoods. It is called Barrio Reus. The facades, once gray and ordinary, now display blocks of brilliant color. Hand-made wrought iron balconies and hand-baked tile provide added interest. Students at Bellas Artes talked the owners of these houses into letting them innovate. A single homeowner refused.

Uruguay has one of the worst climates I know. Hot in the summer, cold and rainy throughout the winter months, and damp to the point of producing year-round mold, it is a particularly difficult place for those who suffer from respiratory problems. Directly above it is one of the dangerous tears in the ozone layer, making the sun a menace to one’s health. Uruguayans are urged not to go outdoors between ten in the morning and four in the afternoon, but try telling that to a people who practically live on the beach. These are some of the country’s downsides. Balancing them is a land of bucolic beaches, sunflower fields, real hospitality, and a people who have a lot to teach.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Uruguay”