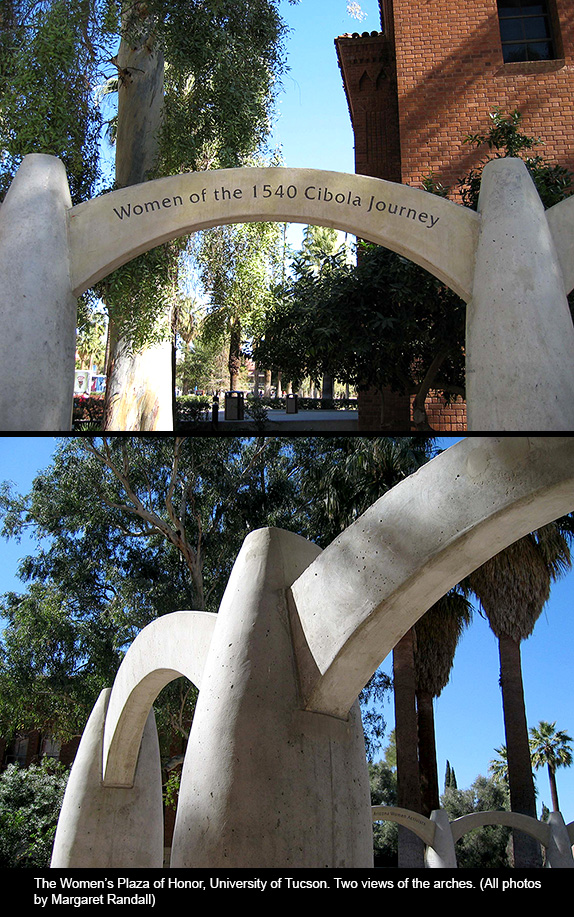

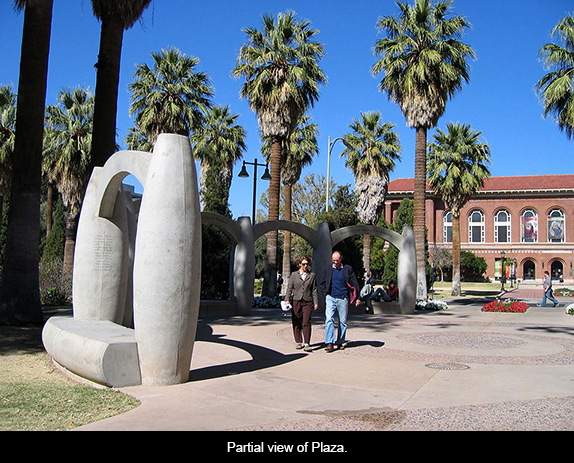

At the University of Arizona in Tucson, a beautifully conceived and executed corner of campus is dedicated to promoting and preserving the history of women: individually and collectively. The Women’s Plaza of Honor, as it is called, is a special and deeply meaningful place that has earned the admiration of women and men throughout the country and around the world. Grand and intimate at one and the same time, it provides a space for remembrance, relaxation, and renewal, as well as a simple stroll, a peaceful lunch in the shade of arches and trees, or a public event that finds its setting the perfect backdrop.

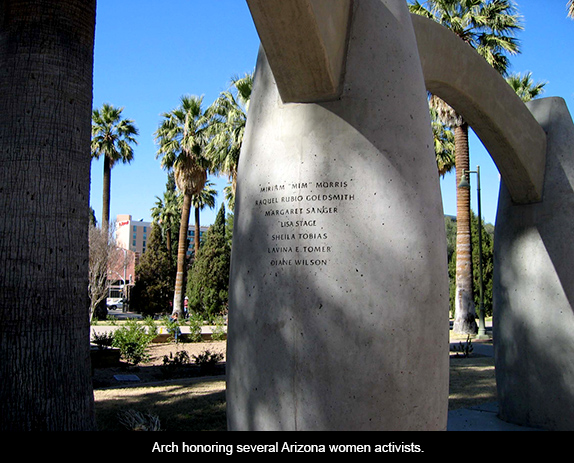

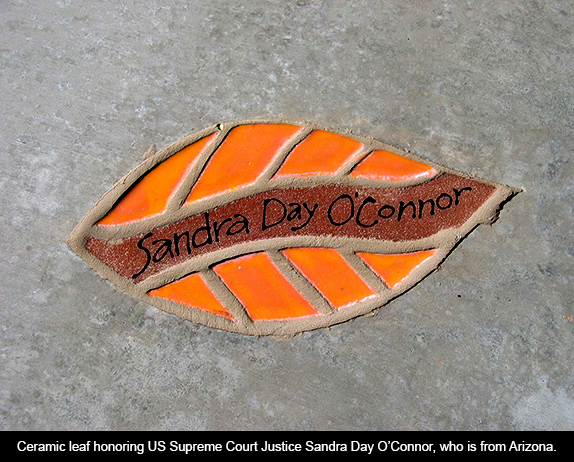

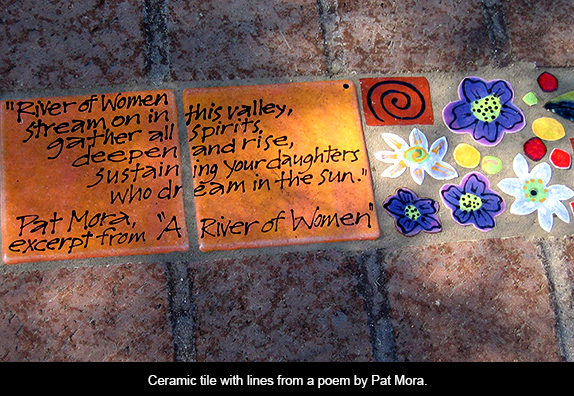

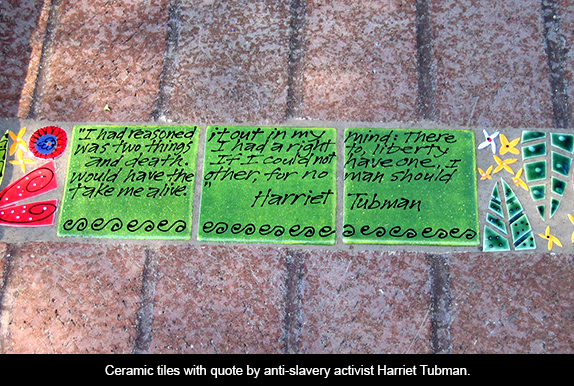

The Women’s Plaza of Honor is located in an area west of Centennial Hall and east of the Arizona State Museum and Haury buildings. It celebrates the lives and accomplishments of women in Arizona and also outside the state. As its webpage states, “Its unique design of plants, lighting and water intermingles with archways, benches and sculptural elements to represent the stages of a woman’s life.” Set in a garden walkway, the names of honorees are inscribed on sweeping arches, elegantly-detailed benches, brightly-colored handmade tiles, and bricks embedded in wide paths. Each honoree’s life story is included in a computer kiosk located in the garden itself, and the data is also available online.

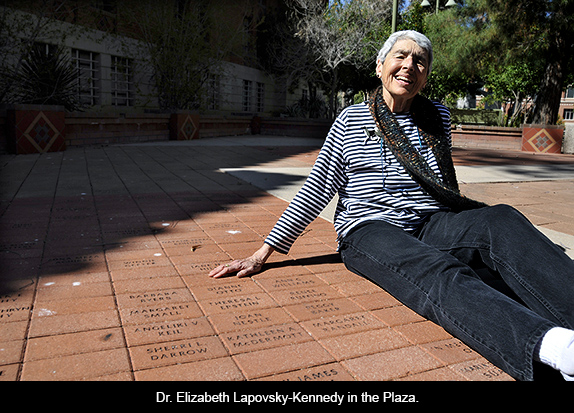

The history of the Women’s Plaza of Honor is a lesson in creativity, collaboration, perseverance and hard work. In June 1998, Dr. Elizabeth Lapovsky-Kennedy had recently come from a long teaching career at SUNY / Buffalo to take a position as head of Women’s Studies at the University of Arizona / Tucson. During a panel at the National Women’s Studies Association meeting, she had heard about the Plaza of Heroines at Wichita State University. The Wichita State plaza had raised $500,000, half of which went toward construction and the other half to an endowment for the university’s Women’s Studies department.

Lapovsky-Kennedy was intrigued by the idea of creating a similar monument to women at the University of Arizona. In the fall of 1998, she presented information about the Wichita State Plaza of Heroines to Arizona’s Women’s Studies Advisory Council (WOSAC), a community advisory board that supported Women’s Studies through fundraising and networking. From that moment, WOSAC members began to imagine their own version of such a plaza, with a unique design and on an even larger scale.

Over the next several years, literally hundreds of women and a few supportive male allies worked on different aspects of the project. Together they discussed what they would like to see materialize at Arizona: a place for peaceful contemplation that conveyed a sense of sanctuary but highly visible to visitors and the public. Administrators, fundraisers, landscape architects, professors, community people and students all took part. Those early years were characterized by bringing a broad range of participants into the planning stages while evolving a truly democratic process for dealing with differences of opinion and the most expedient way to move forward.

When we think of a project of this size and complexity, we might imagine that it developed in a context of ample funding and support. Nothing would be farther from the truth. In March 1999 a number of Arizona state legislators had proposed cutting completely the funding for all four women’s studies programs statewide. Although the project co-chairs and UA Women’s Studies faculty and staff were aware of these challenges, they rarely discussed the obstacles to building and marketing the Plaza. Instead, with consummate tact and creativity the team worked to find common ground with potential major donors, always through the idea of honoring women.

In the initial stages, the amount of money the co-chairs aimed to raise for building the Plaza and endowing Women’s Studies with scholarship and research funds varied; but it was never less than $750,000. As time went on, and the work became consolidated on a variety of fronts, the goal grew to $1.5 million by 2001. Half that amount was intended for construction, the other half for the Women’s Studies endowment. This goal was later increased to $2 million to reflect the number of naming opportunities available in the Plaza design.

The organizers had to decide how to price the various elements in the Plaza, through which they hoped to provide a way to recognize important groups of women or women of great note, as well as a grandmother, wife or sister an individual might wish to honor. After much discussion they priced the Plaza’s larger design elements—arches, fountains, and gardens—at $25,000 each. The benches were priced at $10,000 and $15,000. The light posts and trees were priced at $5,000. Once a substantial number of these items had been sold, the Executive Committee agreed to open up more than 2,000 additional opportunities for under $1,000 each: brick pavers and ceramic leaves for $100, $200, $500 and $750 (depending upon size). This donation structure was designed to encourage major donors to buy the bigger items, while still giving a large number of people the opportunity to honor a family member, mentor or other influential woman, thus adding to the Plaza’s historical record.

It is important to note that all the women who participated in the planning and creation of the Plaza were themselves successful in a variety of fields. They knew what was required to make it in their professions, whether as a scholar, businesswoman, community leader, artist, student or single mother raising a family against difficult odds. They were conscious of women’s history and diversity. Throughout the early 2000s, sub-committees dedicated to making the executive decisions, carrying out the architectural and landscape design, doing continued fundraising, publicity and history, worked tirelessly to solidify what had been achieved and pull together remaining areas of effort.

By December 2004, all the pieces were in place for the groundbreaking. The event was attended by more than 100 guests. A reporter was overheard saying, “This must be something important, because I have never seen so many people at a university groundbreaking.” On September 30, 2005, the Plaza was finally dedicated, with more than 300 comfortably in attendance. Then governor of Arizona Janet Napolitano was the featured speaker. Important university and community personalities were present, as well as the many volunteers whose hard work had brought the Plaza to fruition.

The Women’s Plaza of Honor at the University of Arizona is a work in progress. Twice a year, new names are added to the walkways, benches, columns and plaques at the bases of trees. New biographies, many of them written by the honorees themselves, continue to be added to the database. The Plaza’s web page invites additions, with donation-friendly forms to be filled out if one wishes to buy an element, pay for it online, by phone or mail, and provide a photograph and bio. Purchases are tax-deductible.

I and a number of people I know have had the immense satisfaction of immortalizing women who have meant something in our lives. I’ve felt particularly delighted to honor a young Chicana activist, a seven-year old girl, a great artist, a Colorado river-runner, and a Zapatista guerrilla leader, among others. I started out seeking my honorees within Arizona state lines, but quickly realized that state and national boundaries may be as limiting to this sort of recognition as the gender boundaries that once kept women’s names out of the public eye.

Each time I visit Tucson I try to spend a little time in the Plaza. Each time, the trees are a bit taller, the flowers and shrubs more filled out, and there are more names in evidence. A beautiful fountain recycles streams of water over fluid sculptural forms. The kiosk with its database of honoree names, photos and biographies, reflects the extraordinary number and variety of women whose lives have enriched this and other communities.

When I have time, I sit awhile and enjoy watching the people who have come specifically to experience the Plaza, or simply find it a nurturing place in which to sit and chat. It is exciting to listen to visitors talk about a particular honoree or ask questions about a name he or she may not know. I think my favorite moment to date was watching and listening to a man lead his wife through the space. He wanted her to choose the sort of element by which she wanted to be remembered; he was buying it for their anniversary.

I would love to see such a Plaza on the campus of the University of New Mexico, with its high desert landscape and character, one that would honor the great women of our state and those who have some connection to it. Unless or until that happens, Tucson is not that far away.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: The Women’s Plaza of Honor”