Borders are almost always fictitious lines, drawn by people with power whose interests are served by separating “us” and “them.” Throughout time, they are also malleable. Wars are fought, lost, and won. Borders shift.

So-called human progress seems to drag us in the direction of more borders. The European Union, South American Common Market, and other efforts to eradicate unnecessary lines of demarcation are, sadly, not typical of modern day attitudes toward the ever willful nation state. In recent times some walls have come down; the one separating East and West Germany is a dramatic example. But even after the fortress-like markers are no more, the effects of separation linger for years, dooming some people to lives of want while others thrive.

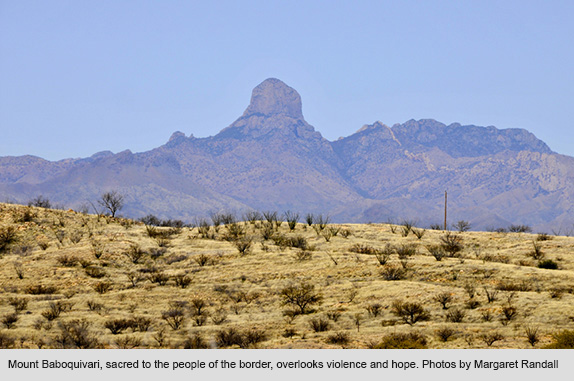

Along with the dangerous border keeping Palestinians from their millennial homeland in what is now Israel, The US-Mexican border is among the most volatile in the world. The Mexican-American border region is defined (by the La Paz Agreement, 1983) as all land 62.5 miles north and south of the international boundary that separates the two countries. It stretches approximately 3,000 miles from the southern tip of Texas to California. Its population is estimated to be approximately 13 million, and is expected to double by 2015. So, the first thing we need to keep in mind is that we are not talking about a slender line but an area with a larger number of inhabitants than many countries. Additionally, there are 154 Native American tribes, totaling 881,070 people, located in the four boarder states that touch on the US side.

We are talking about history: less than 200 years ago the entire area belonged to Mexico. Depending on your point of view, the US acquired or stole a large part of that country in the Mexican American War (1846-48). We are talking about culture: traditions and customs shared by people on both sides of an arbitrary line. We are talking about language: hundreds, if we take into account the indigenous tongues spoken in Native American communities. We are talking about economic distress: an average yearly income of $14,560—considerably below the US poverty line. We are talking about inadequate social welfare: nonexistent or rudimentary healthcare, lack of basic water and sanitation services, and impoverished schools. The unemployment rate along the US side of the Texas-Mexico border is 250 to 300% higher than in the rest of the United States.

And so we are talking about a petri dish for crime. The US-Mexican border is a natural breeding ground for violence of all kinds, and specialized social groups have sprung up to take advantage of the hope and desperation. The murder and disappearance of hundreds of young women in the city of Juárez has attracted attention in recent years; Mexican authorities either cannot or do not want to come to grips with this situation. And life in other border cities and towns is increasingly violent as well.

Mexican narco cartels feed the US demand for drugs by smuggling them through tunnels, in vehicles and even on the backs of individuals who only want safe passage to a better life. Coyotes are those specialized in bringing groups of immigrants across, often taking their money and leaving them to die of exposure on the desert. On this side of the border there are also increasing numbers of mercenary vigilantes, who routinely take the law into their own hands and frequently shoot on site people they suspect of being undocumented. The US Border Patrol, charged with securing the border, is a mix of hard-working professionals and corrupt bullies.

In response to this violence, communities of activists have also sprung up along the US-Mexico border, taking into their own hands the humanitarian concerns both governments refuse to consider. “No More Deaths” was founded in 2004 by several Tucson-area religious leaders, including Catholic Bishop Gerald Kicanas, Presbyterian Minister John Fife, and leaders of the local Jewish community. The founders understood that there was a need for a constant presence on the border to aid migrants and end the increasing numbers of deaths.

The organization was structured as an umbrella group to consolidate and expand upon the humanitarian aid work already being provided by other organizations, such as “Samaritan,” “Humane Borders,” and others. “No More Deaths” began by organizing driving patrols through Arizona’s Sonoran Desert to look for migrants in need of water or medical attention. In the summer of 2004, the group also set up camps called "Arks of the Covenant" to provide a permanent presence during the hottest months of summer. The camps are staffed with volunteers who go on daily driving and foot patrols, often leaving deposits of potable water along known migrant routes.

Art has also had a vital presence in this story of misery and desperation. Innumerable photo exhibits document the border and its movement. Some excellent films have been produced. People have collected items of clothing, water bottles, and other abandoned possessions, left by the thousands who have died (an estimated 5,600 since 1998). These objects may be seen at several small museums operated by those who want to keep the collective memory of tragedy and hope alive.

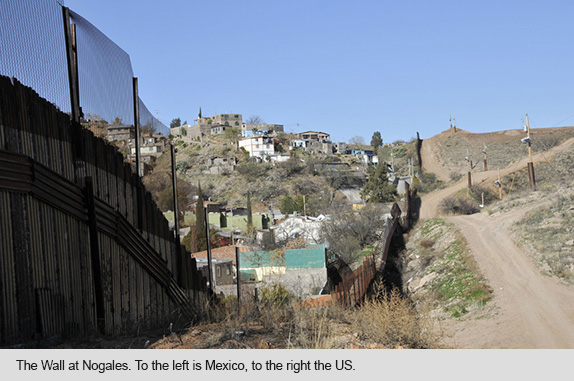

In March of 2010, I traveled to the border area around Nogales with sound sculptor Glenn Weyant, a man who has made of the Arizona-Mexican border a palette upon which to practice his art. Again and again through the years, Weyant drives to the stretch of wall between Nogales and Sasabe, unloads some modest sound equipment from his car, and begins to play the wall—with a cello bow, drum sticks, and his hands. He feels that the vibrations from this music may offset the sounds of terror and despair. At first the Border Patrol tried to stop him. Today they are accustomed to his visits.

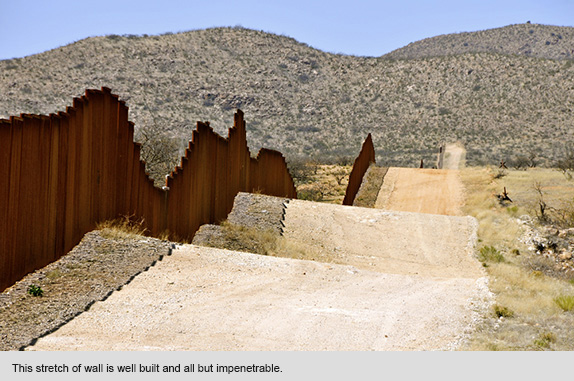

I was fortunate that Weyant invited me to accompany him on one of his trips to the wall. The first thing I learned from him, is that it is indeed a wall, not a fence as our government officials tend to call it. Listening to him make his music, and reading some of my own border poems while standing beside that wall, made a deep impression on my consciousness of border issues. I am not naïve enough to believe our duet changed the balance of power along this violent line. But the experience allowed me to feel a part of history unfolding, and to put some small counterbalance of positive energy out into the parched desert air.

That day we also drove the road that clings for miles to the US side of the wall. We saw a pile of abandoned clothing, left by a migrant whose body temperature had probably heated to the point where he could no longer tolerate it. We saw several simple crosses, marking spots where bodies had been found; and a number of more elaborate shrines. We stopped for pie at a little café in Arivaca, and read the numerous flyers on the walls, promoting one or another humanitarian effort. We observed Border Patrol vehicles, armed to the teeth, and vigilante Humvees, also armed to the teeth.

According to the National Foundation for American Policy, in its report titled “How Many More Deaths?,” in 2012, 477 migrants lost their lives attempting to cross the US-Mexico border. This was up from 375 the previous year. And these are only the reported deaths. How many more bodies lie scavenged by animals or disintegrating into the searing sand across the vast desert reaching north toward shining goals such as Phoenix, Los Angeles, and Houston? Deaths along the US-Mexico border spiked 27% last year.

United States immigration policy, long politically motivated, cruel to families and children, and abetting all sorts of criminal activity, is particularly skewed when it comes to those desperate enough to try to cross our southern border. The Obama administration has actively pushed for immigration reform, and a growing Hispanic voting block has even drawn the support of some Republicans. But as with so many important national issues, our corporate press gives us an erroneous picture of what is actually happening along our southern frontier.

Most importantly, according to the Pew Hispanic Center, net immigration from Mexico has dropped to net zero or less. This means fewer people are traveling north than south. A slight uptick in the Mexican economy, along with the unemployment resulting from the United States’ current economic crisis, may be partially responsible. Danger of dying on the desert, and increased border security also surely play a role. Since the mid-1980s the US Border Patrol has quintupled in size, growing from about 4,000 to more than 20,000 agents. The US government has constructed some 700 miles of fencing and vehicle barriers. It has placed thousands of ground sensors, lights, radar towers and cameras (many of which have never worked). And Customs and Border Protection is now flying drones and helicopters to locate smugglers and immigrants. US Secretary of Homeland Security Janet Napolitano says the border has been secured to a large degree over the past few years. Yet those trying to impede immigration reform continue to demand more border security as a prerequisite to more rational law.

So we have many fewer people entering the country from Mexico, but many more deaths. This alone should give us pause. US agriculture and industry need many more foreign workers than receive visas to enter the country legally. There are believed to be somewhere around 14 million people currently living in the United States without legal status. Many of these people have been paying taxes and contributing to their communities for years. Their children, in many cases brought to the US as infants or small children, attend our schools and have the same dreams of success as children born here. Current US immigration policy tears families apart, separates children from their parents, encourages crime and stimulates violence. By any human measure, we need change and we need it now.

New immigration policy should not be based on what constituency a politician has in his or her district. It should not be influenced by Wild West vigilantism or graft and kickbacks. It should focus on the human element in a situation of need and demand. Mexico is the United States’ second largest trading partner, with $261.7 billion in two-way trade recorded for 2000. That’s $700 million a day. US exports to Mexico that year were more than $110 billion and US imports from Mexico more than $135 billion. This trade has only increased since then. There is no doubt, even beyond the human aspect of broken families and linked cultures, that our two countries need one another.

And the issue of illegal immigration goes beyond Mexico and the United States. Our southern border is also crossed by thousands of immigrants from farther south—Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and elsewhere—who brave unspeakable peril and criminality as they simply seek job opportunities or flee political terror. These men, women, and even children often ride the roofs of freight trains traveling north. Way stations run by humanitarian groups counsel, feed, lodge and offer them medical attention along the way. Many of these people travel thousands of miles, only to be captured and returned to their countries of origin, where extreme poverty or death awaits.

As we watch immigration reform make its stumbling way through Congress, we see far too much misinformation, political wrangling, and susceptibility to voting blocks. Grandiloquent pronouncements often have little to do with reality. Lobbyists defend spurious interests. If we are able to pass any sort of immigration reform, I fear it will resemble Obama’s decimated health care bill, with a far fewer improvements than we need and many concessions to political interests.

Meanwhile, more and more bodies are found on the desert, especially in this season of triple digit temperatures. Forensic specialists in small border towns struggle to identify the bodies that are found, in order to provide closure to anxious families south of the border. Our own Border Patrol grapples with a complex issue, including corruption within its own ranks. Absurd operations, often resulting in sending weaponry into Mexico, are responsible for even more deaths. Coyotes, mid-level members of Organized Crime organizations, and young people who say they would rather live like a king for five years than like an ox for fifty, continue to make money off human misery. And ordinary human beings, who simply share the hopes and dreams we all have, continue to die.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: The U.S.-Mexico Border”