Presenting a couple of new books At George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia recently, I found myself with a free morning. My partner and I decided to avail ourselves of the excellent metro system and spend it in our nation’s capitol, only an hour away. Just a few days had passed since the Republicans had orchestrated the partial government shutdown. After 16 desperate days, institutions had reopened and people were back at work. It seemed an ideal time to try to take the pulse of what had been perpetrated, by talking to the reinstated government workers themselves.

The metro’s orange line took us through bucolic Virginia countryside. The familiar station names of Rosslyn, Foggy Bottom, Falls Church, Farragut West, L’Enfant whizzed by, against a backdrop of lush green. Soon enough we were at Federal Center, one of the stops that services monumental downtown Washington. From there it was a two-block walk to The National Museum of the American Indian, the site we had chosen as our destination.

This part of downtown Washington presents the visitor with all the familiar sights: the abundance of immense square federal office buildings more reminiscent of Soviet architecture than of any quintessential American design, the broad avenues and clean aspect befitting our national political hub (albeit one that has lately shed its dignity), and the iconic silhouettes of the Capitol dome and Washington Monument. The latter, since the earthquake destruction that assaulted it a couple of years back, sports a full-body armature adorned with thousands of twinkling lights.

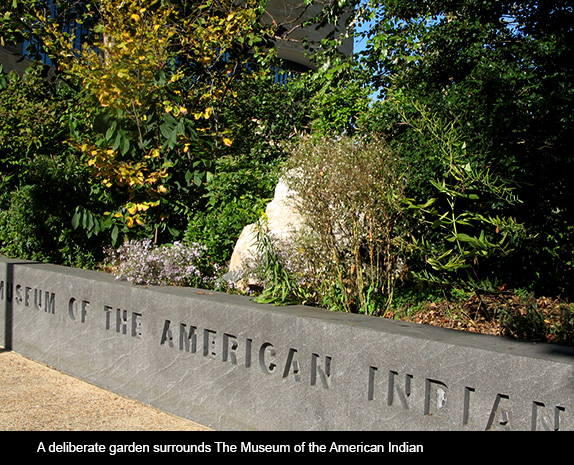

In the midst of all these buildings and monuments, The National Museum of the American Indian is beautifully different. Outside, its four and a quarter acres of gardens simulate wetlands and offer a series of landscape features that give visitors a sense of the world they are about to enter. More than 40 rocks and boulders, called Grandfather Rocks, dominate the area. Cardinal Direction Markers (four special stones) stand along the north-south and east-west axes of the building’s center.

In this garden there are 150 species of more than 33,000 indigenous plants; and 25 native tree species, including Red Maple, Staghorn Sumac, and White Oak. There are Wild Rice plants, Marsh Marigolds, Cardinal flowers, Silky Willows, Buttercups, fall Panic Grass, Black-Eyed Susans, Sunflowers, Corn, Beans, Squash and Tobacco. We are encouraged to think about these plants and what they have given to the original inhabitants of our lands in sustenance and medicine.

Donna E. House, the Navajo and Oneida botanist who supervised the landscaping, has said: “The landscape flows into the building, and the environment is who we are. We are the trees, we are the rocks, we are the water. And that had to be part of the museum.”

Also in the garden are five hand-fashioned clay sculptures which together go by the name of Always Becoming. These were fashioned by Santa Clara Pueblo artist Nora Naranjo-Morse, and are crafted of low-fired clay which eventually will melt into the earth, changing their molecules into whatever may come next.

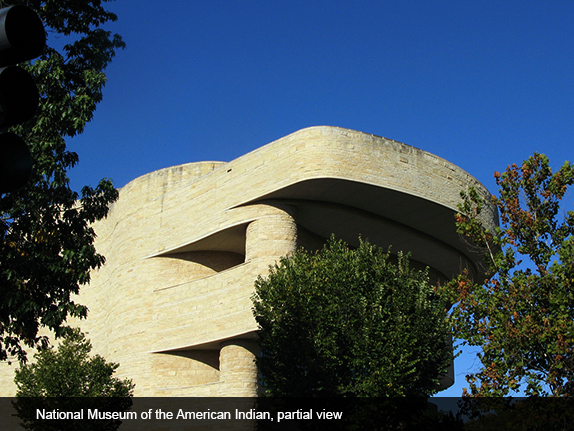

The museum’s architect and project designer was the Canadian Douglas Cardinal of the Blackfoot tribe. Its design architects were GBQC Architects of Philadelphia and Johnpaul Jones (Cherokee/Choctaw). Project architects were Jones & Jones Architects and Landscape Architects Ltd. of the Seattle and Smith Group in Washington, in association with Lou Weller (Caddo), the Native American Design Collaborative, and Polshek Partnership of New York City. Ramona Sakiestewa (Hopi) and Donna House (Navajo/Oneida) also served as design consultants.

The building itself is spectacular, at home on the Washington cityscape while architecturally new and curvilinear, with an organic feeling moving from the surrounding gardens into the structure itself—which is almost completely built along curved lines. The five-story, 250,000-square-foot building is clad in a sunny Kosota limestone that evokes natural rock formations shaped by wind and water.

As part of the Smithsonian Institution, and dedicated to the life, languages, literature, history, and arts of the Native peoples of the entire Western Hemisphere, the National Museum of the American Indian does not charge a visitors fee. The Washington building was opened in September, 2004, at the corner of Fourth Street and Independence Avenue SW. The institution also includes the George Gustav Heye Center in New York City and the Cultural Resources Center (a research and collection facility) in Suitland, Maryland. The beginnings of the impressive collection we viewed in Washington were first assembled at the former Museum of the American Indian in New York, which was established in 1916.

The Washington iteration, however, is unique in that it does not display Indian artifacts presented by colonizers, but Indian life and culture according to the various tribes themselves. There has been some criticism of the new museum: most notably that it focuses on the conflict between Indian peoples and Whites but does not present the conflicts that have arisen between the various tribes themselves. Another complaint I have heard is that too much attention is paid the wealthier tribes, while the smaller more isolated indigenous groups are not as well represented. I would be interested in knowing how the museum decisions were made. In several parts of the museum, however, I read signs urging visitors to “argue with what you see here.” I felt that the exhibitions were very much in flux and evolving.

We started our tour as the literature suggests, on the fourth floor. There a fascinating film depicts native peoples throughout the Americas. In a small, rather intimate, circular theater we watched the main scenes unfold on one of four woven white rug screens, but images were also projected on a domed ceiling and on the uneven surfaces of a large grandfather rock set below all four screens. I had the extraordinary sense of being completely surrounded by another world and its living elements, as well as immersed in the various cultures of its first peoples.

Then we descended from floor to floor, taking in a series of special exhibits as well as the museum’s permanent collection. There are beautiful ceramics from the length and breadth of the continent, intricate beaded work, exquisite woodcarvings, and strong but delicate canoes—among much else. The design and information accompanying each exhibit is in the best museum tradition.

As so often happens, our schedule only permitted us to spend a few hours in a museum that cannot be seen in its entirety in a day or even several days. The museum’s design and exhibition plan, however, allow for a sense of fulfillment no matter how brief the visit.

For us, a joyous surprise was the museum’s cafeteria. Museums, like National Parks, are often characterized by poor food at high prices; the customer has no choice but to assuage his or her hunger and pay up. An exception would be New York City’s Museum of Modern Art, where the large expertly run cafeteria serves delicious dishes at modest prices.

The National Museum of the American Indian also offers a unique eating experience. The Mitsitam Native Foods Café is divided into regional sections, such as the Northern Woodlands, South America, the Northwest Coast, Mesoamerica, and the Great Plains. A large circular space, somewhat reminiscent of a food court, it features a vast array of specialties from many different indigenous cultures. This has to be one of Washington’s best-kept secrets and greatest low-cost gastronomical treats. We delighted in roasted salmon, berries of different sorts, little corn cakes like none we had ever tasted before, and too much else.

Our nation’s capital has a rich collection of museums and national monuments—of historical impact as well as contemporary. All the Smithsonian institutions are free to the public. Private museums charge a fee. Washington is a city where almost everything is located within easy reach of everything else. Its urban area is made for walking, and has excellent public transportation when walking is not an option.

The thousands of men and women who keep these sites accessible, clean, and inviting, didn’t deserve to be furloughed without pay for more than two weeks in October, any more than workers throughout the country deserved such flagrant disrespect. At the National Museum of the American Indian we talked to some of the guards, docents and cafeteria workers about the recent shutdown. Most tried to put a resigned face on the experience, but some expressed open resentment at the attack on their personal economies and wellbeing.

Every city has its museums and every museum has at least some worthwhile exhibits. The National Museum of the American Indian is special among the many excellent museums our country has. Its collection is not subject to the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. When the National Museum was created in 1989, a law governing repatriation was drafted specifically for the institution. It is called the National Museum of the American Indian Act.

In addition to repatriation, the museum dialogues with tribal communities regarding the appropriate curation of cultural heritage items. The human remains vault is smudged once a week with tobacco, sage, sweet grass and cedar. The sacred Crow objects in the Plains vault are smudged with sage during the full moon. If the appropriate cultural tradition for curating an object is unknown, the Native staff uses their own cultural knowledge and customs to treat materials as respectfully as possible. The museum also has programs in which Native American scholars and artists can view the collections to enhance their own research and artwork.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: The National Museum of the American Indian”