River running is a many-layered experience. There is the excitement of running Class V to X rapids, unparalleled for those who want to feel the water’s power challenging the finesse of an expert oars person. There is the calm that comes with floating on tranquil water, letting the river’s natural flow carry you along. River corridors have their unique shoreline landscapes as well, often taking those on such a trip into wildernesses that are inaccessible via vehicle routes and difficult to reach hiking. Some rivers in the western United States offer dramatic scenery, and often make it possible to search out hidden ruins, petroglyphs and pictograph sites.

Rivers are run on inflatable rafts, some of which are rowed by a licensed guide while others invite paying passengers to paddle as well. When the water is deep enough—increasingly problematic in the US American West—wooden dories may be used, and there is nothing like a dory for getting low in the water and feeling one with the current. Motorized rafts are also used, but their rapidity and noise—in my opinion—defeat the goal of a river trip: to get away from city bustle and explore remote side canyons filled with exquisite surprises.

Individuals wait years for the limited number of permits meted out to private trips. It is easier to obtain this permission on some rivers than on others. In this country most people run rivers by signing up for a commercial trip; and these range from the 16- to 18-day journeys on the Colorado through the entire length of Grand Canyon to 3-or 4-day jaunts on Colorado’s San Juan or even New Mexico’s Rio Grande (when it has enough water to support boating). In many places, such as Moab, Utah, you can take a half-or one-day float trip to have the experience of being on a river. Here in New Mexico, the famous Box, in the northern part of the state, offers an exciting white water experience.

Most companies with a history of safe and satisfying river running have guides who are not only experienced oars people but also have a love for and knowledge of the geology, botany, history and lore of the river they run. They have wilderness medical training and are licensed to carry passengers. They cook delicious breakfasts and dinners, and pack lunches for midday stops. And they lead wonderful hikes into the backcountry. The company provides good equipment: tents, sleeping bags with comfortable under pads, and watertight bags for clothing as well as boxes for camera and day necessities. When a trip makes camp in the afternoon, the “unit” (a toilet without plumbing) is set up in a secluded spot, close enough for convenience and distant enough from the camping and kitchen areas so the functions don’t impose upon each other.

My favorite river running company, over many years experience, has been OARS and its subsidiary Grand Canyon Dories. OARS was started by the legendary Martin Litton, who in the 1960s fought so hard along with the Sierra Club’s David Brower to save Grand Canyon’s stretch of the Colorado River from further dam devastation. At 95, he continues to be involved with environmental issues. I’ve also heard good things about Arizona River Runners, Hatch River Expeditions and Sherri Griffith Expeditions. At the western end of Grand Canyon, the Hualapai tribe runs its own single-day trips.

I’ve run the Colorado, the San Juan, and the Green. The latter, beginning at the Gates of Lodore, makes for a beautiful five-day trip through the stunning countryside at the northern tip of Dinosaur National Monument. The jumping off point for this section of the Green is Vernal, Utah, the largest urban area in Uintah County. Unlike most Utah towns, Vernal wasn’t settled by Mormons. Brigham Young sent a scouting party to the area in 1861 but it found the area “good for nothing but to hold the world together.” Still, the town has a Mormon feel. Today Vernal is home to some 9,000 inhabitants, most of whom make their living extracting petroleum, natural gas, phosphate and uintaite. Halliburton and similar companies have offices in Vernal. Tourism accounts for a secondary but growing part of the economy.

The night before putting onto the Green, we arrived in Vernal and chose one of several basics-only lodges. Many of the town’s motels displayed “no vacancy” signs, attesting to the presence of hundreds of seasonal oil field workers and others. Advance reservations are recommended.

Finding a decent place to eat was no easier that locating a room; fast food or slow food of a similar quality is par for the area. The town seemed to us to have a split personality. On the one hand, those dealing directly with tourists seemed friendly enough. On the other, people in the street didn’t seem that happy to welcome a lesbian couple like ourselves, or the interracial couple we quickly guessed must be members of the group with which we would put onto the river the following morning. We introduced ourselves, and for comfort in numbers went out to dinner together.

Vernal’s main street was lined with large equidistant planters overflowing with pink, purple and white petunias. A water tanker made its slow way along the thoroughfare, spraying the precious liquid at each planter. This was 2010, and Vernal seemed determined to pretend there was no drought.

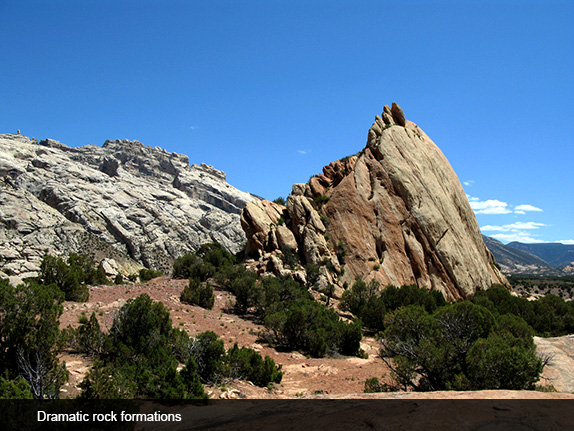

The next morning, putting onto the Green, our impressions of Vernal faded quickly before the natural beauty that surrounded us. The river was flat where our guides readied the rafts, tied our dry bags aboard and fitted our life jackets. The tall multi-colored cliffs that form the Gates of Lodore were just ahead.

Here the Green, after winding across the broad valley known as Browns Park, turns toward the south and makes a direct path into the mountains in front of it. It enters deep canyons filled with the rapids that challenged Major John Wesley Powell when he passed through in 1869 on his voyage south to the Colorado. It was Powell who named the location, based on a poem by Robert Southey, “The Cataract of Lodore.”

Southey’s poem is of another era and of a style that only very occasionally holds my attention, but it captures the feel of all wild rivers in lines such as: “Confounding, astounding, / Dizzying and deafening the ear with its sound. / Collecting, projecting, / Receding and speeding, / And shocking and rocking, / And darting and parting, / And threading and spreading, / And whizzing and hissing, / And dripping and skipping, / And hitting and splitting, / And shining and twining, / And rattling and battling, / And shaking and quaking, / And pouring and roaring, / And waving and raving, / And tossing and crossing, / And flowing and going, / And running and stunning, / And foaming and roaming, / And dinning and spinning, / And dropping and hopping, / And working and jerking, / And guggling and struggling, / And heaving and cleaving, / And moaning and groaning, / And glittering and frittering, / And gathering and feathering, / And whitening and brightening, / And quivering and shivering, / And hurrying and skurrying, / And thundering and floundering; / Dividing and gliding and sliding, / And falling and brawling and sprawling . . .” The litany continues. In spite of the poem’s arbitrary rhyme, each one of Southey’s verbs is dramatically applicable to the Green.

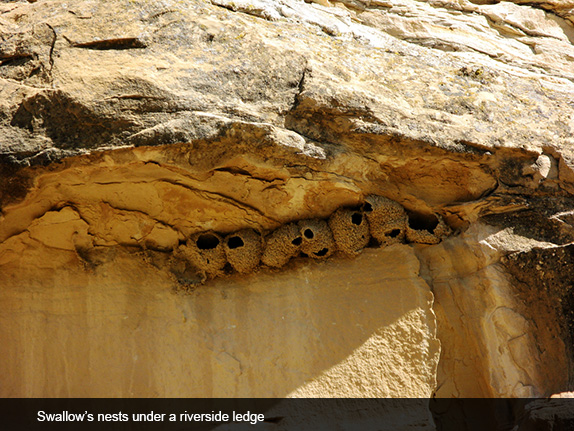

Our days on the Green were wonderful: the perfect mix of medium sized rapids, long tranquil floats, and forays into the countryside to the sites of unusual examples of Fremont rock art. The rugged mountains on either side of the river twisted and folded back upon themselves, revealing a sculptural landscape that often took our breath away. We passed few other rafts, and despite the fact that at one point a shoreline road is briefly visible, mostly felt that we had gotten away from it all—the main objective of any river trip.

A word about Dinosaur National Monument, which is also worth some exploration either before putting onto the Green or after taking off the river. Located on the southeast flank of the Uinta Mountains, on the border between Colorado and Utah and at the confluence of the Green and Yampa Rivers, the Monument consists of the Dinosaur Quarry just north of the little town of Jensen, Utah, and several other fossil sites. Jaw bones and other parts of Allosaurus and Abydosaurus are believed to have washed into the area and to have been buried in the Morrison Formation laid down in the Jurassic Period some 150 million years ago.

Also of interest are a number of nearby Fremont pictograph sites. Many of these aren’t noted on area maps in an effort to discourage the considerable vandalism that has been inflicted upon them in recent years. For those interested in viewing some of these images, a couple of hours driving slowly along the main road and turning in wherever there’s a sign is more than worth the effort.

An even more interesting series of petroglyphs and pictographs can be seen at Dry Fork Canyon, just 10 miles north of Vernal. Look at a map, or ask almost anyone for directions. Dry Fork is a world renowned, 200-foot-high Navajo Formation sandstone cliff located on private property but accessible to the public. All that the owners of the Sadie McConkie Ranch ask is that visitors not damage the rock carvings and obey all signs. Getting up to the ledge and walking through this gallery of ancient images requires a bit of a scramble in places. But nowhere else can you see more petroglyphs in one area.

The Gates of Lodore is an ideal river trip for children as well as adults. The rapids, while exciting, are nowhere near the Class 10 variety you find in Grand Canyon. The land hikes are short and not at all difficult. And 4 or 5 days on a river is the perfect introduction to rafting.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: The Gates of Lodore”