Economic hardship. Miles of emptiness surrounding outposts of hope where a handful of brave homesteaders scrape a meager living from bone-dry land. This description might as easily be written today as 70 or 80 years ago in the midst of the Great Depression. And it might be written about dozens of places in our struggling state of New Mexico.

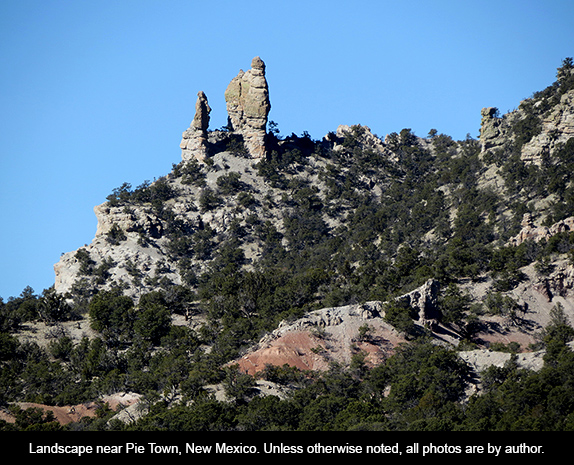

A desert’s dearth of water is a constant here, more so in its vast southern regions that often lack the yearly snow packs and forested areas that in most years past have come through to save the north. As desolate as our geography may be, however, we also have a history of proud settlers, immigrants from elsewhere as well as Native peoples. These hardy men and women have found ways to sustain themselves, made homes, borne children and grandchildren, and left a trail of idiosyncrasy and meaning.

Magdalena, Datl, Pie Down, Quemado and other communities that dot the great San Agustín Plains across the southwestern part of the state, are all examples of this hardiness and pride. Some are villages with several hundred to a couple of thousand inhabitants. Others are smaller. Each has something unique going for it. Datl may be one of Catron County’s most interesting towns, no part of it more so than the Eagle Guest Ranch, a friendly one-stop-meets-all-needs lodge, restaurant, bar, and service station where the quality of goods and services brings a sigh of relief from travelers coming in from the great emptiness that is the surrounding country. Rock climbers go to Datl for the Enchanted Tower, a spire of rock that offers interesting routes.

Pie Town, a smattering of houses straddling the Continental Divide and US 60, is about as lonely and yet unusual as communities come. Its name dates to the small café established by Clyde Norman in the early 1920s, and although there have been periodic suggestions for change, residents insisted on keeping it. Indeed, pies have long been the attraction, but visitors beware: the several places selling the staple are not open during the harsh winters. I drove through in February, only to find all doors shut and a sign on one of the cafés announcing it would reopen on March 14th. The second Saturday in September the village holds its annual Pie Festival, with music, dancing, a crafts sale and—of course—pies.

To be in Pie Town during pie season is heaven. We’re not talking ordinary baked goods here. I’ve been there, and gorged myself on the specialty at The Daily Pie, when the menu advertised New Mexican apple (spiced up with green chili and piñon nuts), boysenberry, key lime, chocolate chunk crème, strawberry rhubarb, peach walnut, and even peanut butter! I’d say that savoring a serving of Pie Town pie is worth a drive south from Albuquerque through the haunting countryside that makes up Catron and adjacent counties.

Just 26 miles west of Socorro, Magdalena is a community with several old buildings reminiscent of better times and ongoing efforts to turn it into an arts destination. In June 2013 the main village well stopped yielding water, leading to a period of conservation during which other New Mexico communities and organizations donated drinking and stock water for distribution to residents until local wells were brought back into operation a month or so later. Many of us remember this dramatic period, which may be a warning prevue of what’s on the agenda in many other parts of the state and country. Just last month Governor Jerry Brown of California declared his state to be in a water emergency situation and prescribed severe rationing. New Mexico has an ongoing struggle with Texas over water rights.

Magdalena used to have a fascinating animal feed store that serviced the area from Socorro all the way to the Arizona line. The two women from the East who operated its most recent incarnation worked hard to make it a success. They got to know the community and made a space for what they hoped could be future cultural activities. But the recession dug in its heels and the feed store failed. I have no doubt that Magdalena will rise again; it’s that kind of place.

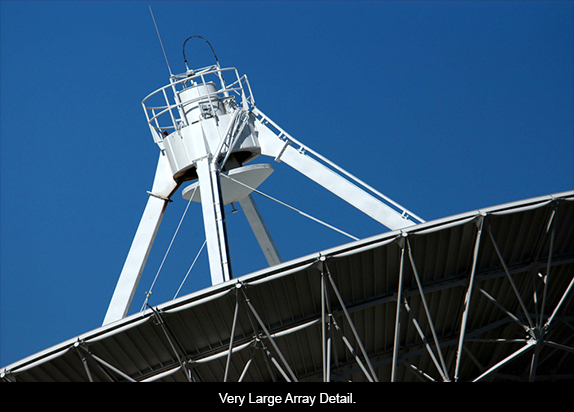

Catron County is home to several unique spots, some artistic, some scientific, all historic. Between Magdalena and Datl is the Very Large Array, the fascinating collection of immense radio telescopes situated on tracks and thus periodically reconfigured so that they may listen efficiently to the universe. As you drive through this seemingly empty country and come over a slight rise, you suddenly begin to see the huge white dishes—like futuristic terminator figures, each the size of a building several stories tall. If the clouds are piled up before a summer storm, the dishes look even more compelling against the dark sky. A side road less than a mile long takes you to an inviting visitor center, where displays and a continuous slide show explain the role this multi-piece telescope plays in working with other such sites around the world and exploring outer space. You may or may not understand how the sounds picked up by those immense ears translate into brightly-colored images on a screen, but at the very least you will delight in those images.

The town of Quemado is the point of departure for a visit to Walter De Maria’s land art, The Lightning Field. This 1977 work, according to its web site, “is comprised of 400 polished stainless steel poles installed in a grid array measuring one mile by one kilometer. The poles -- two inches in diameter and averaging 20 feet and 7½ inches in height -- are spaced 220 feet apart and have solid pointed tips that define a horizontal plane. A sculpture to be walked in as well as viewed, The Lightning Field is intended to be experienced over an extended period of time. A full experience of The Lightning Field does not depend upon the occurrence of lightning, and visitors are encouraged to spend as much time as possible in the field, especially during sunset and sunrise. In order to provide this opportunity, Dia offers overnight visits during the months of May through October.”

To visit The Lightning Field, you contact the reservation office, pay the fee for an overnight stay, and then drive to Quemado on the appointed date. Several years back, when we went, we were picked up in that small town and driven to a beautiful hand-hewn log cabin at the edge of the site. This cabin has room for six visitors, each set of two occupying its own room with bath. The man who delivered us showed us a simple but tasty meal that had only to be heated up; provisions for the following morning’s breakfast were also on site. There is no cell phone service, but a telephone exists in the event of an emergency.

The idea is that visitors spend the afternoon and night alone in a high small valley surrounded by hills. Walking around and through the grid of stainless steel poles, accompanied by an occasional cow, is a unique experience. Most people I know who have been there have raved. I found the installation interesting, especially as early morning and late afternoon light create a changing glow. I also felt that in some way it was a desecration of the land. I wondered what made the artist feel compelled to add a man-made structure to country that was already grand and intimate, colorful and mysterious. Still, the overall experience was one I would chalk up as interesting.

All these recent additions to the San Agustín Plains and vast areas stretching into southwestern New Mexico, are off-beat overlays in a place that has welcomed hardscrabble people willing to eek survival from an unforgiving land for many decades. Before the settlers and homesteaders, Native Americans called this home; pieces of ancient clay pots and flint tips can still be found throughout the region. Pie Town, at an altitude of 8,000 feet, is typical and atypical. Many of today’s residents are descendants of families that settled there during the mid- to late 1930s. They were refugees from Oklahoma and Texas, fleeing the Dust Bowl and the devastation it wrought. Today its residents are still mostly loners, libertarian types, with a need for solitude, very interesting family histories, and their own outlook on life.

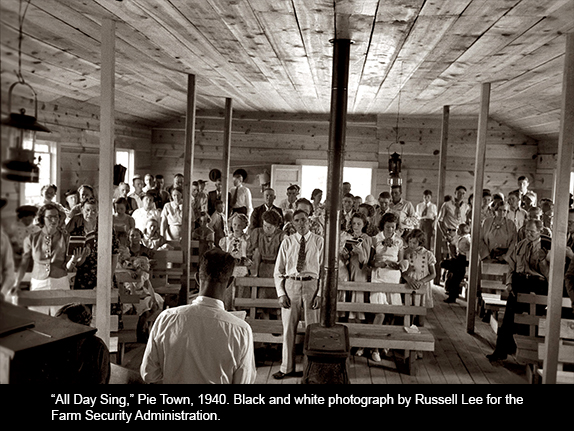

Russell Lee, a photographer who worked for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) during the New Deal, produced a body of important work about Pie Town and its people. The New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum, in Las Cruces (4100 Dripping Springs Road) is currently showing an exhibition of Lee’s colored photographs of the town. Thirty-seven of these images are on display in the Museum’s North Hallway. The “Color of Pie Town” exhibit opened in October of 2013 and will run through Oct. 19, 2014. I would like to see an exhibit of Lee’s black and white photographs of Pie Town as well. The black and white medium lends itself particularly well to reflecting the texture of life during the Depression.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Pie Town”