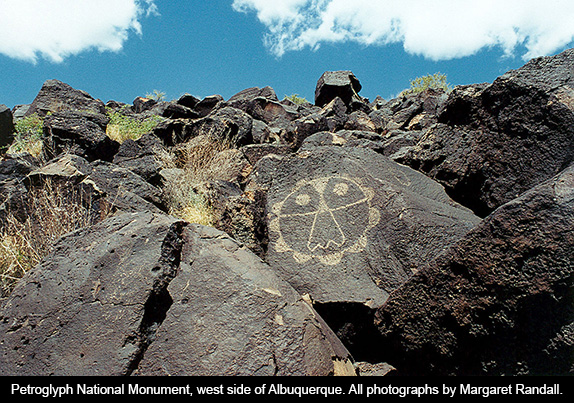

Stretching across open spaces or etched on hidden rock faces throughout several mysterious west side canyons along the basalt escarpment on Albuquerque’s west side, approximately 24,000 drawings of stylized humans, animals, birds, and abstract symbols adorn the fragmented volcanic spill spewed by a line of dark volcanoes. This is a unique destination that, sadly, attracts few visitors to our city—or even those who live here. Hiking there over the years, I have rarely encountered more than two or three others.

One of the largest known petroglyph sites in North America, Petroglyph National Monument has been managed by the Park Service and the City of Albuquerque since its June 27, 1990 authorization. This dual management does a nice job of running a visitor center where information about the site is available, keeping the trails safe, a pit toilet clean, and parking orderly. Its record of protecting the petroglyphs themselves has been less successful. Petroglyph National Monument has not been exempt from a series of controversies in which the interests of several groups have been at odds for years.

Boca Negra and Piedras Marcadas canyons, both to the north of the visitor center, are the more intimate of the accessible areas. Short trails rise through jumbles of rock, where images surprise the visitor around each bend. The larger area, south of the visitor center, is Rinconada Canyon. This is where a two-mile loop trail takes one past a panorama of petroglyphs, some close enough to touch, others scattered over the ridge above. Needless to say, although these are the marked trails, the petroglyphs themselves are not limited to these viewing areas; they undoubtedly extend for miles across this land.

To visit any of the petroglyph sites, take Unser Boulevard from Interstate 40 (exit #154) and go north three miles to Western Trail. Turn left onto Western Trail until you come to the visitor center. From Interstate 25, take Paseo del Norte (exit #232) and proceed west to Coors Road exit south. Then go south on Coors to Western Trail, turn right and continue to the visitor center.

Several miles to the west of the petroglyph concentration, and reachable from Atrisco Vista Boulevard, the Volcanoes Day Use Area invites visitors to get close to the volcanoes that, thousands of years ago, spit the lava that is canvass to this vast gallery. The Volcanoes Day Use Area is reachable from Interstate 40, by taking Exit #149 to Atrisco Vista Boulevard and turning right onto Volcanoes Access Road.

The National Park Service doesn’t charge an entrance fee to visit the Monument. But the City of Albuquerque does charge a small fee to park at Boca Negra Canyon. For private vehicles this charge is $1 on weekdays and $2 on weekends. If they have a seating capacity of 25 or less, commercial buses pay $25. Full-size motor coaches with a capacity of more than 25 must pay $50.

The petroglyphs, or rock art, throughout this area are believed to have been carved by Ancestral Pueblo peoples and early Spanish settlers; the more traditional animals, birds, stars and geometric forms by the former, the occasional brands and Christian crosses by the latter. The earliest art is thought to have been done from 700 to 400 years ago, the oldest in a distant past and the most recent just before the city of Albuquerque was founded in 1706.

Because all the petroglyphs are exposed, with no shade from trees or human-made structures, the best time to visit these sites is spring and fall, without our extreme summer heat or winter cold. Walking the two-mile loop beneath a huge New Mexico sky on one of our brilliant temperate days is an experience that links a reverence for ancient voice with present day possibility.

As I say, Petroglyph National Monument has had its share of controversy. In 1989, before the Monument was established, a Tibetan Buddhist Stupa was build and consecrated on what was then private land. Over the objections of Harold Cohen and Ariene Emery, who owned the land, the National Park Service used eminent domain to seize it and make it part of the Monument. The Stupa was not removed, but all other buildings were razed. On June 10, 2010, the superintendent of Petroglyph National Monument sent an email stating: “while soils are being stockpiled nearby for the future construction of an amphitheater, the National Park Service has no plans for the Stupa.” The Monument website was also updated to describe planned construction projects and clarify that the Stupa was not to be demolished.

The greatest unresolved controversy, however, has come from the encroachment of urban development. For at least two decades, groups of Native peoples and their allies have protested a series of projects that would endanger, damage or destroy the petroglyphs. Despite this protest, the City of Albuquerque finally succeeded in building a four-lane highway directly through the site. The city argued that this 2.7-mile project “implemented a much needed transportation corridor while enhancing the natural surroundings and minimizing the roadway footprint.” It pointed to “creative additions such as using a short concrete masonry unit retaining wall that mimics the black basalt rock in color and texture” along with “various pieces of public art along the road way and a footbridge over the road.”

This language is as transparent as the desecration that had already taken place. In order to complete the highway, boulders bearing petroglyphs were taken from their original sites and relocated. The city applauded preserving them in this way, even as it ignored an elemental rule of anthropology that says that location is all-important in understanding the significance of ancient architecture, objects of use, and art.

According to documents posted on June 6, 2012 by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), “The Petroglyph National Monument is a major asset for the City of Albuquerque and New Mexico, but its rich trove of cultural and natural resources is threatened by the inability of the City and the National Park Service to cooperatively manage the two-thirds of the monument that is City-owned land.” It was noted that there were no consistent management standards or patrols protecting the rock art for which the Monument was created.

The City refused to allow NPS rangers to patrol or enforce Park Service rules on City lands, meaning most of the Monument. Due to skewed priorities and City service cutbacks, most of the site was left unpatrolled. In a July 25, 2011 letter to PEER, NPS Intermountain Regional Director John Wessels had written: “The NPS currently has no agreement with the City of Albuquerque that holistically authorizes NPS to enforce the entirety of 36 CFR Part 2 on lands owned by the City ( . . . ). We would welcome such an agreement and we have, in the past, proposed such an agreement with the City, but the City has not acceded to this proposal.”

Throughout his term, Albuquerque Mayor Richard Berry consistently came down on the side of big development. New residential projects extend farther and farther west, depleting our precarious water supply but making millions for big business.

Meanwhile, those of us who value our ancient heritage continued to be concerned about the petroglyphs. As with rock art throughout the world, there are always those who—out of brutish disregard, ignorance, or fundamentalist belief—desecrate such treasures. Director of PEER Daniel Patterson echoed the sentiments of many of us when he said that Petroglyph National Monument is “not just a regional but a national treasure which deserves the same protections as other national parks.”

When a new five-year agreement was signed on June 13, 2013, it seemed some progress had been made. Patterson wrote as follows of this agreement: “It is fair to say that the Park Service and the City of Albuquerque are finally on the same page with respect to managing Petroglyph. While PEER has never shied away from criticizing the Park Service when we thought it appropriate, we do not hesitate to praise the agency when it gets things right.”

For its part, the City of Albuquerque agreed to the lead on fire response and emergency medical services. Both entities pledged to assist the other, and seek joint training and maximum coordination. Despite this new show of cooperation, however, Petroglyph National Monument remains at risk. Surrounded by an urban area, it is vulnerable to scars from graffiti and off-roading as well as illegal dumping. In addition, its ancient petroglyphs and rock art have been increasingly targeted by thieves and vandals. Nothing in the June, 2013 agreement guarantees that trash dumps at the head of Piedras Marcadas Canyon will be removed, egregious motocross scarring in the Northern Geological Window will be remedied, or decades-old accumulations of matted tumbleweeds impeding visitor access and posing a potentially explosive fire hazard will be cleaned up.

“Now the hard work of healing Petroglyph should move forward,” Patterson added. “PEER will be following closely the process of actually improving conditions on the ground.” The group has decommissioned its on-line petition urging that Petroglyph be managed up to national standards.

We who live here and treasure our resources must remain vigilant.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Petroglyph National Monument”