Driving west on I-40, we pass the Petrified Forest. Making a quick gas, food or bathroom stop, we often say we should explore this National Monument one day, but we’re usually on our way to or from the trip’s main attraction and put a visit off for another time. Coming home from Grand Canyon one day in early September, we decided to take a couple of hours and find out what the site has to offer. We were glad we did.

Since we were moving west to east, we entered the Petrified Forest from Holbrook. We turned off the highway at exit 285, and took a few moments for our 13-year-old grandson to explore an inviting-looking rock shop. This one, replete with large fanciful looking dinosaur figures in garish colors, had a yard full of petrified wood in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Inside were split geodes with their brilliant crystal colors, polished pieces of agate and other stones, and the marvelous cross-sections that reveal a range of beautiful fossils. What greater artist than nature!

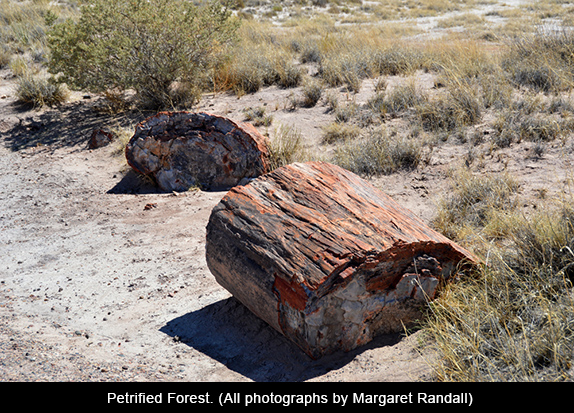

Then we followed the signs 18 miles on State Road 180 to the Monument’s south entrance. There we were immediately welcomed by the Rainbow Forest Museum, a small building surrounded by short trails bordered with large “logs” in a profusion of mysterious colors.

Petrified wood isn’t really wood. The trees lived in a forest more than 200 million years ago. As continents shifted to form the configuration we have today, the region was uplifted and climate changed. What was once a tropical environment became semi-arid grassland. Over the immense expanse of time, wind and water wore the rock layers away.

Petrified wood (from the Greek root petro meaning "rock" or "stone"; literally "wood turned into stone") is the name given to a special type of fossilized remains of trees or other vegetation. The transition to stone occurs through a process called permineralization. The organic materials are replaced with minerals, mostly a silicate such as quartz, while retaining the original structure of the stem tissue. What remains are “trees” composed of rock.

Unlike other types of fossils which are typically impressions or compressions, petrified wood is a three-dimensional representation of the original organic material. The petrification process occurs underground, when the wood becomes buried beneath sediment and is initially preserved due to a lack of oxygen, inhibiting aerobic decomposition. Mineral-laden water flowing through the sediment deposits minerals in the plant's cells, and as the plant's lignin and cellulose decay, stone take their place.

And so we see a forest of felled trees, its pieces holding their tree shape but having morphed into multicolored agate. The “bark” retains its rusty brown surface, while crosscuts reveal rainbows of color. At rock shops and other places where objects of petrified wood are sold, they have often been polished to enhance their brilliance.

In this multi-million-year process, fossils of insects and other creatures have become embedded in the wood. We are granted a glimpse of geologic scale: the large trees and vast dunes as well as the tiniest life forms caught in time. At the Petrified Forest, paleontologists have been studying the fossils since the 1920s. They have found the skeletons of crocodile-like Phytosaur, one of North America’s earliest dinosaurs, as well as the Aetosaur Stagonolepis, a large heavily armored reptile that ate plants. Most prevalent, however, are the smaller variety of life forms.

There was much to explore around the Rainbow Forest Museum, before heading north. Moving through the Petrified Forest in this direction, you pass a number of spots where interesting smatterings of logs catch the eye. At Crystal Forest there is an easy 0.8-mile paved trail through a landscape of exquisitely colorful logs that once held glassy amethyst and quartz crystals.

Next is Jasper Forest, with its hundreds of petrified logs, once encased in a bluff, now strewn across a broad valley. A little farther on is Blue Mesa, again with its trail—this one three miles in length. Or, you can choose a self-guided one-mile loop trail with a short steep section. Agate Bridge turned out to be one very long log stretched across an arroyo bed; it is supported by a cement beam which, although undoubtedly necessary, diminishes its impact (it looks like one cement beam atop another).

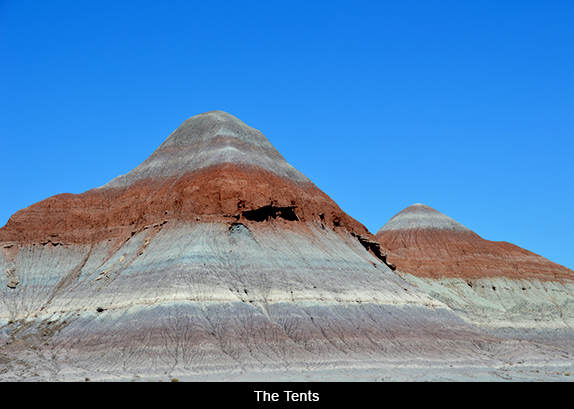

The Tepees are easy to spot. This is where sections of Painted Desert come into prominent view, and several tall tepee-shaped cones to the left of the road display the dusty rose and rich gray strata so typical of this landscape.

Newspaper Rock—one of many sites bearing this name in the high desert Southwest—attests to the area having been populated by Ancestral Puebloan peoples. A large number of petroglyphs can be spotted with binoculars or the long lens of a camera. A much more satisfying place to view petroglyphs is just a bit farther on, at Puerco Pueblo.

Here a partially stabilized 100-room village may have housed as many as 200 people between 1250 and 1380. A small building, finished but not yet in use when we were there, will eventually contain some of the archeological artifacts discovered in the area. Close to the trail, some very interesting petroglyphs are almost near enough to touch—certainly near enough for contemplation or photography.

From here, we linked to the short loop that exists at the north end of the Monument. Kachina Point and the Rim Trail were renovated by the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. Views of the Painted Desert are breathtaking. Here, too, a Pueblo Revival-style structure called The Painted Desert Inn—no longer functioning as such—has been named a National Historic Landmark. Stop and take a look inside. Interesting exhibits alternate with remnants of the Inn when it was in operation, including a soda fountain with 1920 prices: a chocolate sundae for twenty cents or a ten-cent cup of coffee!

Whatever direction you decide to travel, the Petrified Forest / Painted Desert’s 28 mile loop offers lots to see. The north end of the Monument has its own Visitors Center, with a 20-minute orientation film, bookstore, gas station, modest cafeteria-style restaurant and gift shop.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Petrified Forest and Painted Desert”