For westerners, New York City is often the subject of misconception or a bad joke, much as several years back Albuquerque residents scoffed at our own state capital by wearing those little pink and white I don’t care how they do it in Santa Fe buttons. A TV commercial for a popular brand of salsa has a couple of hardy-looking cowboys looking aghast at a third who consumes salsa made in New York City?! The implication is that the nation’s most populous city, described by many as the cultural capital of the world, can’t possibly produce hot sauce to compete with the local favorite. Something between awe and jealousy.

New York City a mean spirited place? Nothing could be farther from the truth.

Those who have never lived in NYC often repeat the hearsay about New Yorkers being rude, ungenerous or unhelpful. Untrue as well. New Yorkers are sophisticated, street smart, gritty, and almost unfailingly kind to strangers. This modern-day Tower of Babel, where 800 languages are spoken—sometimes in neighborhoods where a foreign tongue is the only one spoken—is immeasurably rich in human caring, cultures, customs, lifestyles, and unique attractions.

I was born in Manhattan, lived in the city’s suburbs until I was ten and my family moved to New Mexico, and returned in the late 1950s as a young adult. I wanted to be a writer, and held the provincial belief that to succeed in that profession I needed to live in New York. Those were the years of Black Mountain and Deep Image, two new poetic schools. The Beats were beginning to read in cafes and parks. I got to know many of the poets, and read my own incipient verse for the first time in public. But my closest friends were painters, mostly the Abstract Expressionists who were about to explode on the scene in the US and eventually throughout the world.

I lived in the city for the next four years, and I credit those years and the people with whom I interacted for teaching me creative discipline. Most of us prioritized our creative work: painting, writing, dancing, theater, or whatever the genre. We worked at odd jobs only as much as was necessary to pay low rents and put food on the table. We lived in cold-water flats or, in the case of the visual artists, in old factories we called lofts. We painted or wrote long hours during the day, and at night got together at the Old Cedar Bar, on University Place near the corner of 8th Street. Sometimes we visited each other’s apartments or lofts to share what we were doing.

The city seemed fragmented. Our neighborhood was our world. We talked about spending most of our time below 14th Street, suspiciously scornful of the wealthy New Yorkers who lived uptown. Yet most of my painter friends longed to get into a 57th Street gallery. A friend and I often walked from the Lower East Side all the way up to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: a good seventy blocks. We might part with a quarter or 50 cents, and spend all day in that museum.

Manhattan’s Harlem back then was not a place white people could go. Today it is more tolerant. But it still exudes a history of Black artistry as well as many substandard schools and overcrowded apartments. The area’s Hotel Theresa housed Fidel Castro and his entourage when they first came to the city following the victory of the Cuban revolution. The famous Cotton Club hosted the best dance bands through prohibition and beyond; I never went there, but my mother told me stories of its charms. The Apollo Theater, where I once heard Ella Fitzgerald sing, was central to The Harlem Renaissance. Such greats as Billie Holiday, Marvin Gaye, and Stevie Wonder graced its stage. The theater’s 2013-2014 season still features the best: James Brown’s magic meets an international who’s-who of dance masters, Ellington for Christmas with Savion Glover, Liz Wright and the Abyssinian Baptist Church Choir, a tribute to la Guarachera de Cuba, Celia Cruz, by those who played with her, the return by popular demand of Apollo Club Harlem, and more.

Nearby Spanish Harlem began by housing immigrants from a variety of Spanish-speaking nations. Today, like its African American sister, people of all nationalities live there. President Bill Clinton’s choice of Harlem as the location of his post-presidency office complex, brought renewed attention and an upscale investment in a section of the city previously known for its poverty. Puerto Ricans and Dominicans have carved neighborhoods that resemble their countries of origin, just as Irish, Germans and Italians did in earlier generations. New York’s Chinatown is one of the largest in the world outside of China itself.

The Statue of Liberty was renowned for welcoming immigrants since it first graced New York’s harbor. The colossal statue was designed by Frederic Auguste Bartholdi, dedicated on October 28, 1886, and was a gift to the United States from the people of France. Between 1892 and 1924, 12 million men women and children from Europe passed through the official entry point at Ellis Island; and the Ellis Island Immigration Museum, not far from the graceful lady, presents the complex history of successive waves of immigrants: how each group was received and the struggles it endured before integrating into the life that has so often, and so erroneously, been called a melting pot.

Enclaves of Hassidic Jews walk the streets in their black coats and long side curls; while Muslim women, some in burqas, watch their children running and swinging in hundreds of city parks. Immigrants from Russia, China, Yemen, Somalia, Afghanistan, Haiti, El Salvador, and more than a hundred other countries pour into this multiracial city, establishing their centers of worship, cultural manifestations, ethnic restaurants, and pungent spice markets. Approximately 37% of New York City’s inhabitants are foreign born. The Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca (1898-1936) immortalized the city in his famous poem “A Poet In New York.” But exile and refugee status anywhere in the world means displacement and the pain of shattered memory. New York, because many of its neighborhoods are like small replicas of the countries from which its immigrants come, may be slightly less hostile.

New York City’s gay community is larger than the one in San Francisco. On June 28th, 1969, members of the largely Latino gay community responded to police violence at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village. This is widely considered to be the beginning of the gay liberation movement in this country. The Stonewall still exists, and is a popular landmark. In the little park across the street, a George Segal sculpture, composed of a gay male couple and a lesbian couple, continues to attest to the importance of the city’s gay LBGT community.

New York also has a high degree of income disparity. In 2005, the median household income in the wealthiest census tract was $188,697, while in the poorest it was $9,320. In this hub of industry, commerce and trade, there has been wage growth in the higher brackets, while wages have stagnated for middle and lower income groups. In early 2011, the average weekly wage in New York County was $2,634: high if compared with the rest of the nation. But life in the city is extremely expensive, especially in the better neighborhoods. And tens of thousands of undocumented workers toil without job security or benefits at the most menial jobs.

Built dramatically vertically rather than horizontally, New York City is located on one of the world’s largest natural harbors. International trade is hot and heavy. Each of the city’s five boroughs—The Bronx, Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, and little Staten Island—are also separate counties in New York State. The city traces its roots to 1624, when colonists of the Dutch Republic founded a trading post and two years later named it New Amsterdam. The city and its surroundings came under English control in 1664, and it was renamed New York. For five years, from 1785 to 1790, it served as the capital of the United States. Since 1790, it has been the country’s largest city.

When outsiders think of New York, they usually focus on Manhattan, the borough best known for its nightlife, museums, performance venues and sports stadiums. Over time, Brooklyn, The Bronx, and Queens have also established a reputation for unique parks and museums. In Brooklyn, for example, Prospect Park and the Brooklyn Museum of Art, hold their own alongside similar destinations anywhere in the world. The Bronx Zoo is undoubtedly one of the world’s largest and best. The US census bureau estimated the city’s 2012 population at 8,336,697, and the entire urban area is close to 22 million. But this figure gives little sense of how many people work and play in the city on a given day. New York, especially the island of Manhattan, draws visitors from everywhere. In 2011 the number of tourists reached 50 million.

There are so many separate (but connected) places and peoples in New York, each of them offering those with particular interests weeks, even months, of exciting exploration. The urban transit system, especially the various components of its famous subway, is in a class of its own. It is a city beneath a city. It’s first line opened in 1904, and since then it has expanded to allow riders to get to almost every part of the metropolis. Today it is the world’s largest rapid transit system by length of routes as well as number of stations (468 at last count). Some stations still have their original beautiful old tile work. Almost 55% of New Yorkers use mass transit to commute to work each day (elsewhere in the country some 90% of commuters drive to work or carpool). More than a billion and a half people ride the New York subway every year.

Grand Central and Pennsylvania railway stations are hubs for interstate trains coming from and departing for other cities. Three major airports serve the metropolitan area: John F. Kennedy, Newark Liberty, and LaGuardia. And the city has some magnificent bridges, among them the George Washington connecting Manhattan with New Jersey, the Verrazano-Narrows connecting Brooklyn and Staten Island, and the incomparably elegant Brooklyn Bridge between Brooklyn and Manhattan. This latter was made famous by Hart Crane’s first and only long poem, “The Bridge” (1930). Tunnels, parkways and expressways complete the picture.

It would take months for a visitor to view the collections held by New York City’s museums. There is the previously mentioned Metropolitan, one of the world’s great art museums. It is so large there is no way you can even attempt to see it in a day. Great wings exhibit art from different nations and time periods. As a child, I was fascinated by the Egyptian wing. As a young adult, I loved Renaissance painting and the delicately-painted Grecian urns. I have yet to visit the recently opened Islamic wing, but by all accounts it is superb.

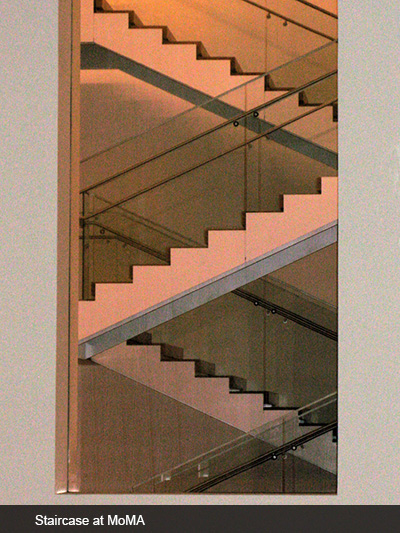

There is the architecturally dizzying Guggenheim, the Whitney Museum of American Art (which has the largest holding of twentieth century US art), and the Museum of Modern Art (or MoMA), reopened in 2012 after several years of renovation. MoMA’s collection of contemporary art is among the richest in the world. These days, when I visit one of these museums I often take one of my grandchildren—or they take me.

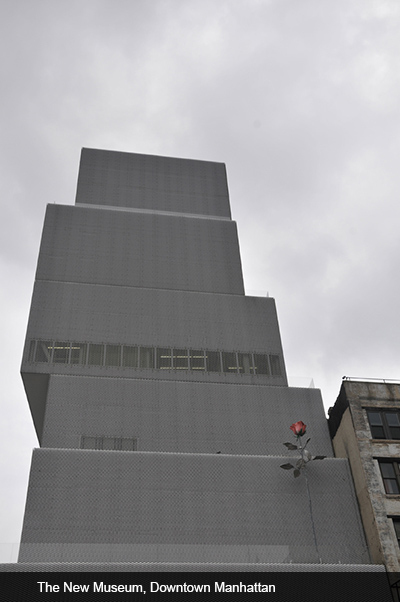

In downtown Manhattan, The New Museum takes artistic expression beyond its usual limits. The aforementioned Brooklyn Museum of Art and Ellis Island Immigration Museum are also stellar. Queens now has a fine art museum. And the iconic Museum of Natural History not only exhibits dinosaur and whale skeletons, but houses spectacular collections of pre-Columbian and Polynesian art. All these museums also host temporary exhibits that often take years to curate. These are just a few of the city’s hundreds of great museums, displaying just about anything of interest to the public—and some items that are of interest only to very small segments of the public. It’s also worth noting that every museum in the city system has a small, oft-ignored sign near its ticket counter. This sign tells visitors that if they cannot afford the price of entrance, they are welcome to pay what they can.

An array of private art galleries, as well as street fairs where neighborhood art can be seen, extend the art-viewing experience beyond the confines of museums. Near the division between Brooklyn and Manhattan, the old neighborhood called Dumbo fills with families on Sundays. It might be said that the city itself, with its extraordinary architecture and great urban planning, is one great museum.

Within the city of New York there are seven state parks, including a wildlife refuge, pre-Civil War sites, beaches, trails, and a marina. Central Park, in the middle of Manhattan, has stables, riding and hiking trails, and a lake. Hundreds of hidden corners and small neighborhood parks contain historical monuments and graves of famous New Yorkers.

Albuquerque’s own Caleb Smith, who grew up here and earned his undergraduate degree at the University of New Mexico, famously walked and photographed every street in Manhattan, documenting his experience at newyorkcitywalk.com. His photographs of Broadway are in the New York Historical Society's collection, and he contributed photos to the Museum of the City of New York's recent exhibition The Greatest Grid. Caleb died this year, much too young. Anyone interested in going beneath the surface of the great city can’t do much better than to tread the footsteps made by this unique historian.

There are many tourist attractions for which New York City is justly famous: its Broadway and off-Broadway (and now off-off-Broadway) theatrical productions, the various cultural events at Lincoln Center, the Rockettes of Radio Center Music Hall, Madison Square Garden, Yankee Stadium, Coney Island, St. Patrick’s Cathedral and St. John the Divine, the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island, Times Square (especially on New Year’s eve), Chinatown, Greenwich Village, Wall Street, the art deco Chrysler Building (1930) and towering Empire State (1931), and of course Ground Zero, the tragically disappeared World Trade Towers which suffered the greatest loss of life and treasure of the three places hit on September 11th, 2001.

The vast crater, where Towers 1, 2 and 7 once stood, is gradually being filled with a new series of buildings—a collective phoenix rising from ashes. The new site will include One World Trade Center, a 9/11 memorial and museum, and three other office towers. One World Trade Center is the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere and third tallest in the world. The first office tower, a museum telling the story of loss, and a monument to honor those whose lives were cut short in the terrorist attack are already finished, and the entire complex is scheduled for completion in 2014

New York is a city meant for walking. Hundreds of thousands of walkers and cyclists make it the most energy-efficient large city in the nation. Long distances are best traveled by subway, bus or taxi. But a walk through any neighborhood holds unexpected surprises: a tiny triangle of green, blocks of architecturally rich brownstones or buildings, shops and markets selling the most diverse specialties, sidewalk cafes where people-watching brings all sorts of sights and an opportunity to hear almost every language on earth.

Down in Greenwich Village, Washington Square Park is a venue for chess players, street musicians, and people of all ages and interests. Just a few blocks farther north, Union Square still maintains its tradition of soapbox orators. On Sundays, Union Square breaks out one of the great farmer’s markets anywhere. On the Lower East Side, Tompkins Square Park still hosts aging immigrants—men and women sitting on its benches taking the air and chatting. Every one of the city’s five boroughs has a neighborhood park, known for its ethnic community or some unique activity.

One of the city’s great recent attractions is the High Line, an elevated park built along an old unused railway track. It converts a mile-and-a-half spur of the New York Central Railroad known as the West Side Line. This spur once brought freight into Manhattan, mostly meats and cheeses. The tracks are still visible, and a shallow ribbon of water runs alongside them, allowing people to bathe their bare feet on hot summer days. In 1999, the non-profit organization, Friends of the High Line, was formed by Joshua David and Robert Hammond, both neighborhood residents. They advocated for the Line’s preservation and reuse as public open space. In 2004, the New York City government committed $50 million to establish the park. The southernmost section, from Gansevoort Street to 20th Street, opened on June 8, 2009. It is reachable via five stairways and elevators at 14th and 16th streets. On June 7, 2011 a second section opened from 20th to 30th streets. I hope more sections will be added.

The High Line is planted with trees and other vegetation native to the city. Birds sing, and occasional roving music combos also contribute their sounds. Lounge chairs can be found the length of the park. But far and away the most interesting aspect of The High Line is the opportunity it provides to view New York from surprising new angles. New York is a vertical city, and those who walk its streets or ride its aboveground transport are constantly craning their necks for glimpses of various parts of its impressive skyline. Up on The High Line, you can look directly out and across. At times you almost feel you can touch a nearby building, or have an intimate look into the window of a kitchen or living room. The East River runs alongside the park, and the contrast of the waterway with architectural gems such as the Geary Building, can be breathtaking.

This, then, is my New York. I hope it encourages some of you to make it yours.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: New York City”