Monument Valley, a magical area that straddles the Arizona/Utah border just north of Kayenta, is a well-known travel destination. It lies within the Navajo Reservation, and can be reached via Highway #163. The elevation of the valley floor goes from 5,000 to 6,000 feet above sea level. Rising from this height are vast sandstone buttes, some a thousand feet tall. They are clearly stratified, their lowest layer composed of Organ Rock Shale, their middle section made of Chelly Sandstone, and their uppermost layer of the Moenkopi Formation capped by Shinarump Conglomerate. Between 1948 and 1967, the southern reach of the Monument was mined for uranium.

As evening descends, the great towers and spires pull blankets of shadow up around their shoulders, finally completely covering themselves in darkness. With the following day’s sunrise those shadows fall away, revealing an incandescent glow of pinks, purples, oranges and reds. Weather is often dramatic here, brilliant desert sun or dark roiling clouds casting the monoliths in different lights.

Lesser-known Mystery Valley, just to the south, really is a mystery. Only a small fraction of those taking tours to its famous counterpart hire guides to explore Mystery. And a guided tour is the only way one can get there. Monument Valley may be seen on your own, if you have the high-clearance 4-wheel drive vehicle appropriate to its makeshift road conditions. Or you can take a tour. Mystery may be seen only with the latter.

This is high desert country. The Colorado Plateau. It is Navajo land, and the Diné refer to it as Tsé Bii’ Ndzisgali, which means valley of the rocks. The tribe finally has more of a commercial presence than it did back in the 1920s when Harry Goulding and his wife “Mike” built a home up against one of the imposing buttes and established a trading post where they exchanged food and other supplies for hand-woven rugs and handmade jewelry. In those days the Navajo also acted as guides, taking the Gouldings’ visitors throughout the valley. Gouldings’ was the only name of the game. Today the tribe runs its own tours from a small wooden shack near the Park’s visitors center.

My partner Barbara and I had a hankering for Colorado Plateau country and recently took a road trip to see—yet again—some of its wonders. We hadn’t been to Monument Valley for years, and never to Mystery Valley, so we decided to start there. The heavy rains we’ve experienced throughout the Southwest during much of September had washed the landscape clean, but now it was cool and dry. All the colors seemed richer. In places the desert floor was so recently cleansed we didn’t see a single animal or human print.

Although four years ago the large View Hotel joined Gouldings’ as a possibility for lodging, we only knew of the latter and made reservations there. We later discovered the View is even more expensive, which is saying a lot. Our room at Goulding’s was $214 and it was nothing to write home about. Accommodations are basic, food at the restaurant is merely adequate, and the somewhat carnival-like atmosphere that embraces disgorging tour buses is utterly at odds with the natural beauty of the place. Still, staying at Gouldings’ is probably better than staying at the View, or 60 miles away in the small town of Mexican Hat.

Gouldings’ has an interesting history. It is part of the valley’s modern day lore. The Gouldings established themselves in the late 1920s, but the Great Depression hit a decade later. The couple was in danger of losing everything when Harry learned that the Hollywood director John Ford was looking for a dramatic location to film his next movie. Harry and “Mike” literally camped out on Ford’s doorstep until the director received them. When they showed him photographs of the valley he was hooked. He asked if they thought they could house and feed a crew of 100, and they said they could.

That first Ford movie filmed at Monument Valley was Stagecoach starring John Wayne. Others followed, and the setting is still used today as a backdrop to movies, commercials, and fashion shoots. According to popular culture critic Keith Phipps, “its five square miles have defined what decades of moviegoers think of when they imagine the US American West.” All this history is on display at a small onsite museum, where John Wayne films can be viewed as well as more spiritually focused shows. The long history of Ancestral Puebloan and modern Navajo life is also depicted, though superficially.

We’d seen Monument Valley, so decided to visit Mystery. Gouldings’ group tour was listed at $83 per person. If we wanted to go alone, accompanied only by a guide with a four-wheel drive vehicle, the cost for the two of us would have been close to $500! So we decided to drive the six or seven miles to the Navajo Tribal Park-run visitors center and see what was on offer there. We found that for a third of what we would have paid at Gouldings’ we could take off then and there with our own guide.

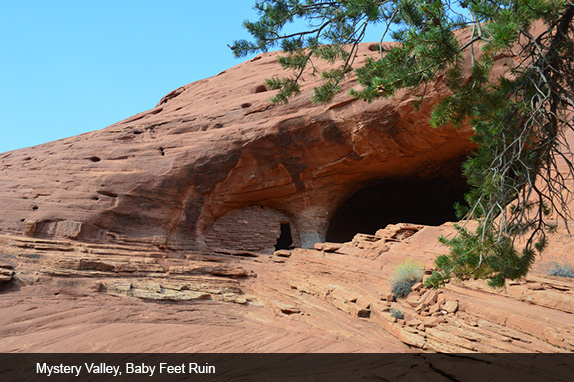

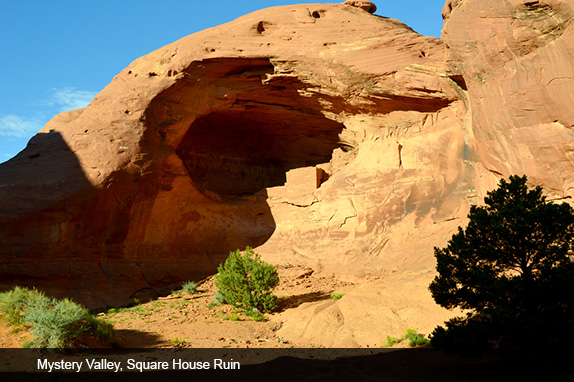

Her name was Yolanda, and she turned out to be knowledgeable, interesting and extremely forthcoming. For three hours she took us over almost impassable deeply rutted roads through Purple Sage, Greasewood, Rabbit Brush and other wild grasses to a dozen or so small ruins hidden among Mystery Valley’s giant sandstone domes. Accustomed to seeing the numerous ruins of multi-room and often multi-story communities, I was surprised to see these brief sites that looked as if they had housed one or at best two families. In Mystery Valley they are located far from one another, adding to a sense of isolation. There must be tens if not hundreds of thousands of such sites hidden in Utah’s convoluted canyon country.

The names by which these sites go today are Baby Feet, Many Hands, Bachelor House, and Square House among others. Much of the remaining stonework is thin and delicate, as if defense had not been an issue. One senses pride of construction and wellbeing, rather than danger. As with other ruins on the Colorado Plateau, these were inhabited from around 325 to 950 AD.

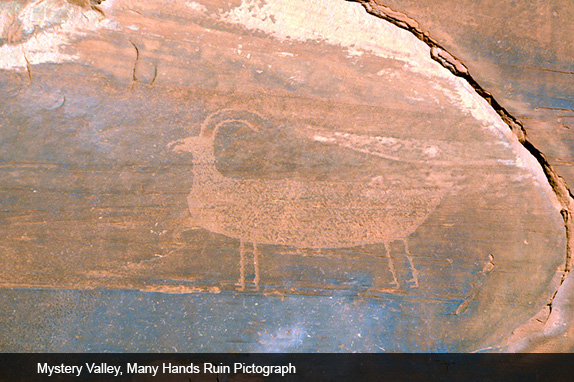

A few of the sites were richly adorned with petroglyphs and pictographs. The back wall of Many Hands, in particular, showed hundreds of prints of human hands, natural white paint blown around the outlines. At this ruin there is also a finely drawn animal: the antlered head of a mountain goat or sheep on a large bird-like body. On the stone floor at the entrance to Baby Feet, a pair of small child’s feet are incised in the stone.

Exploring this valley, so aptly called Mystery, was a fulfilling experience. After the rather Disneyesque atmosphere at Gouldings’, and even the raucous overly crowded scene at the Tribal Park’s visitors center, spending time with a guide who clearly felt an ancestral connection to the sites we saw, in an infrequently visited area (we only saw one other vehicle in the three hours we were there), was authentic and calming. Yolanda, who had worked on the reservation for several years as an EMT, talked about the desert plants she and her family use to supplement Western medicine. When I commented that as a guide she must meet a variety of people, she told us about the recent visit of John Glenn. She had been impressed by his modesty and interest in the ancient sites, as well as by the sweetness of his wife.

Arches

After a couple of days at Monument and Mystery, Barbara and I made our way slowly to other parts of this rich landscape we had somehow missed on previous trips. We drove south on #191 to Blanding, where we stopped to visit the Edge of the Cedars archeological museum. It had been recommended to us many times before, but we’d always been too much in a hurry to get to our next destination. The Edge of the Cedars collection is spectacular, especially its pottery, baskets, sandals and tools. It is well worth a leisurely stop.

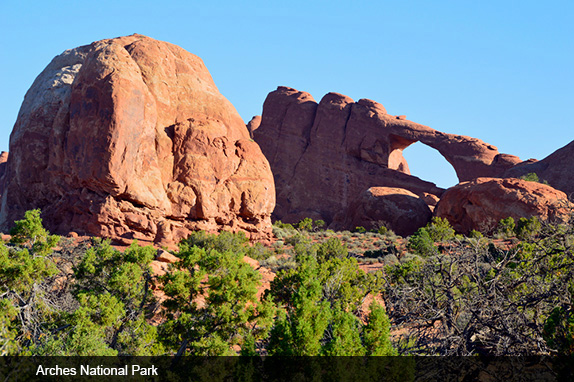

Continuing south on #191, we detoured onto #316 to the astonishing overlook from which we could see The Goosenecks, two impressive loops made by the Colorado River as it winds around imposing cliffs. Then we retraced our way north for a couple of days in Moab, home to Arches and Canyonlands. Repeat visits to both Parks is always wonderful, and we always discover something new.

This trip we also decided to drive north out of Arches and take #316 (another #316) to Dead Horse Point. This is a Utah State Park, yet another point from which one can look down on the Colorado’s dramatic meander around desert bluffs. This is a great destination for cyclists. Unfortunately, if you look slightly to the left of the main overlook, there is a large open pit mine: a blight on the landscape not mentioned in any of the literature and something of a shock in otherwise pristine country. Utah is indeed a state of contrasts, often proudly displaying its great natural beauty while not being able to resist making money from what lies beneath that beauty.

Driving slowly, stopping often, without the haste that characterized us back when we were forever in a hurry so as to be sure to make time for this hike or that sunset or sunrise, the Four Corners region of Arizona, Utah, Colorado and New Mexico takes on a whole new aura. Perhaps my conviction that we are spoiling our wild places more rapidly than we can preserve them is what makes me want to take my time. Perhaps it is simply that this is my heartland, the place that renews my spirit and causes my creative juices to flow.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Mystery Valley”