Modern day Mexico City is one of the largest urban areas in the world, second only to Tokyo and at last count sheltering 26 million people. Approaching by air, if the thick blanket of smog allows one to see more than only its two majestic volcanoes, it seems to stretch forever. It was founded as Tenochtitlán in 1325 as an Aztec altepetl (city-state), and it became the capital of the ever-expanding Aztec Empire in the 15th century, until taken by the Spanish in 1521.

I imagine the shallow marshy lake cut through by causeways leading to the city’s island center. I see Moctezuma coming out to greet Cortéz, believing his arrival the fulfillment of a prophecy about bearded men, half human half horse, who would visit one day. The two men could only communicate with the help of their small female interpreter, Doña Marina or La Malinche. Her parents had given her in slavery to Cortéz and, although she had no control over her destiny she would subsequently be known as “the woman who slept with the enemy,” a traitor to her race (in Mexico the term malinchismo became synonymous with betrayal). That is, until a feminist revision of history came along and told her heroic story in a more honest way.

Tenochtitlán: city of gold and precious stones. Its architecture and art dazzled Spanish eyes. And Moctezuma bestowed great gifts upon the conquerors. But the Spaniards weren’t satisfied. Complete destruction was their goal. When Cortéz asked for a room full of gold, Moctezuma complied. The invader murdered him anyway, and the mestizo era began: a mix of bloods that would eventually lead to foreign domination, grinding poverty, extraordinary culture and art, and a cosmopolitan aura unequaled anywhere.

Mexico City, built upon ancient Tenochtitlán, holds layer upon layer of cultural evidence. Around any modern street corner one may come upon remnants of Spanish colonialism or Aztec building stones. Sometimes these three great cultures coincide, as in Tlatelolco, The Plaza of Three Cultures, where middle-class high-rise apartment buildings stand beside a colonial church and an Aztec ruin stretches silent in the shadows. Of course there are many other cultures present as well: indigenous Mexico is made up of 62 separate nations with their own languages, many of which have living literatures. The most recent census recognizes 15.7 million indigenous people (14.9% of the country’s total population). Immigration from throughout the world enriches this mix.

Tlatelolco is the place where, on October 2, 1968, the Diaz Ordáz administration attacked a peaceful demonstration of students and others who had been protesting authoritarian government policies for several months. The country was days away from hosting that year’s Summer Olympics. Travelers were beginning to cancel, and the administration feared losing its large investment. Those who were there that afternoon won’t forget the paramilitary forces, identified by white gloves worn on one hand. Nor will they ever be able to silence the barrage of gunfire, tanks and helicopters. Victims tried to take refuge in the apartment complex, where the stairways ran wet with blood. The unequal battle lasted close to five hours. Hundreds were murdered.[1]

In the 16th century, Tlatelolco and Tenochtitlán were twin cities: the former laying to the north and the latter to the south, on the western edge of Lake Texcoco. The whole area was wet, marshy, and in places still a lake. In Nahuatl tetl means rock and nōchtli prickly pear cactus, thus the name was traditionally taken to mean “city where prickly pears grow among the rocks.” However, a manuscript from later in that century suggests a variation on the vowel, so the name’s etymology remains unclear.

The lake was and is called Texcoco. Ancient Tenochtitlán occupied slightly more than three by five square miles. Modern Mexico City covers 573.36 square miles today. The vast metropolis, that once ended around Bucareli Street near the modern city center, spread and spread. Swamps gave way to land mass. Canals cut through the area, and canoes rivaled foot travel. Today’s extreme pollution is largely due to the exhaust from hundreds of thousands of older cars. Neither a subway system, carved from the shifting rock base in the 1960s, nor a double-decker expressway built in the 1990s, have been able to alleviate the gnarl of traffic. For decades now all but the newest automobiles are prohibited from circulating one day a week and one Saturday a month. This has helped a little but not enough.

Mexico City is exhilarating, progressive, and alluring. It probably has more parks and museums than most other modern metropolises. Since the victory of the Mexican Revolution, in 1910, President Benito Juárez’ motto “Respect for the rights of others means peace” has translated into immigration policy that has given refuge to peoples from all over the world—including victims from the Spanish Civil War, Nazi Germany, and the Latin American dictatorships of the 1970s and ‘80s. These arrivals included great thinkers, writers and artists, and cultural activity is amply subsidized. The city embraces its multiple cultures with grace and respect.

The PRD, or Revolutionary Democratic Party (the country’s organized Left), controlled the capital for two six-year terms in recent years, and positive changes were notable. The city became cleaner, crime became less of a problem, and marriage equality and other legal advances were instituted. But today, great areas of Mexico are controlled by narco traffickers organized into large competing crime syndicates.

Corruption and cover-up are endemic, from the highest governmental levels to the base. Journalists and others who dare expose the violence and demand accountability are routinely kidnapped and murdered. There is constant tension between those who live in heavily gated communities and those who take to the streets in daily protest against such massive crime. The November 2014 disappearances (probable murders) of 43 education students in Ayotzinapa, in the southern state of Guerrero, was only the latest in a very long line of crimes committed by drug lords in collusion with the police and protected by power. Ordinary citizens don’t give up on their country. But some analysts admit Mexico may now be a failed state.

On a recent trip, I felt the terror and the depth, the anguish and the pride. Such a complex and contradictory weave of making and doing shows itself in layers of civilization that don’t simply succeed one another through time, but coexist in startling ways. If one stands still enough and listens hard enough, one can see the ghosts, hear their voices. They may be nobility or slaves from the fluid social structure of ancient Tenochtitlán, those secretly executed after the 1968 massacre at Tlatelolco, students murdered last year who only hoped to become rural schoolteachers, or anyone else along the way. They may be children dead from hunger, laborers defeated by work, or women battered to death by the country’s particular brand of machismo.

Although I lived in Mexico City in the 1960s, and have returned many times since, I had never visited the Templo Mayor museum just behind the Zocalo or city’s enormous main square. The Templo Mayor was Tenochtitlán’s main temple complex, dismantled by the Spanish when they constructed their colonial replacement and long hidden beneath the city’s giant cathedral.

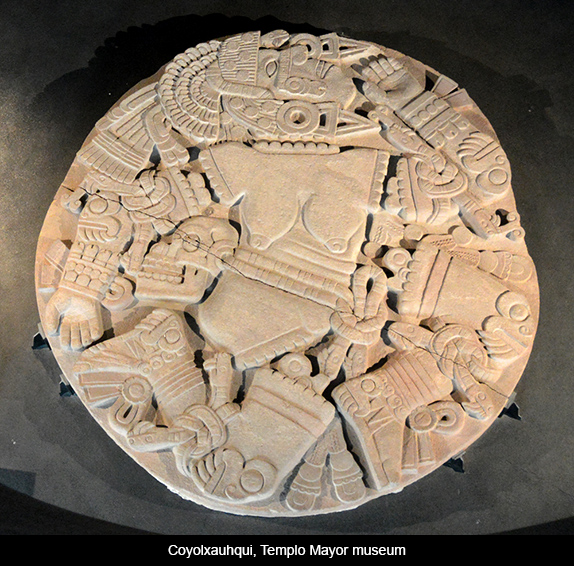

During sewer repairs at mid-20th century, workers came upon the first significant finds, including a massive stone disc depicting the nude dismembered body of the moon goddess Coyolxauhqui. The extraordinary piece is ten and a half feet in diameter. Soon other pieces were revealed. The great Aztec calendar stone, weighing more than 20 tons and now in the Museum of Anthropology and History, was found halfway up the pyramid that once stood at this spot.

Major excavation began in 1978. It was discovered that the city, constructed over seven distinct periods, was built on successive layers atop one another. The resulting weight caused the original structures to sink into Lake Texcoco’s sediment, and they now rest at an angle rather than horizontally. Teams of engineers, anthropologists, archeologists, ethnographers, architects and others work with dental tools, making their way back through history centimeter by centimeter (approximately one centimeter a month). The ruins of Tenotichtlán have the advantage of being accompanied by written references, something lacking at many other ancient sites. Additionally, the dark humidity of burial cysts and ofrendas (ritual collections of objects, small animals, and foodstuffs) made for ideal climate control in terms of preservation.

The Templo Mayor museum is exquisite. If one starts at the top, one gets a sense of how the inhabitants of Tenochtitlán lived and died, what fauna and flora were part of their world, their relationship with nature, and what they wore and ate. Interestingly, although Mexico and all of Mesoamerica are corn-based societies, not a single kernel of corn has been found at this site. There is evidence of beans, squash, amaranth and chia (as in a precursor to the clay chia-covered figures so popular today). A friend speculated that perhaps corn was eaten by the ordinary people who lived outside the ancient city walls.

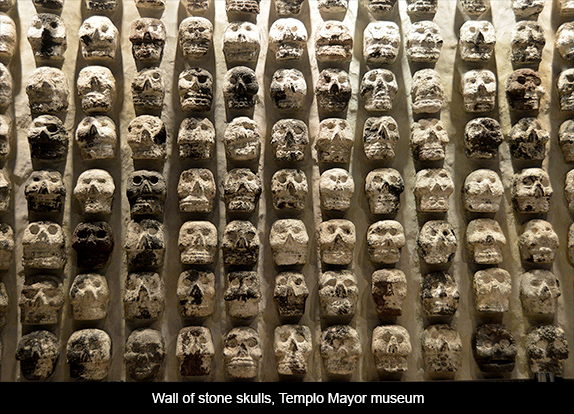

As one descends to the lower floor, the great monumental finds come into view. There are numerous larger than life-sized figures, a whole wall of stone skulls, and then—at the very bottom—the amazing deep bass relief image of Tlaltecuhtli: the largest such figure found to date on the continent. Tlaltecuhtle is male and female in a single body, and its powers are dual as well. A gush of blood spills from his/her mouth. The depth of the stone varies, from perhaps eight inches to over a foot. The enormous plaque was once brightly colored. Today, only faint vestiges of color remain. This wondrous image was discovered face down. A jagged piece is missing from its center. Otherwise it is perfect.

Even without being a student of Aztec culture, it is clear to me that Tlaltecuhtli has something to say to us today. Birth and death, war and peace, body and spirit: all must be in balance for life to continue and flourish. And as the ancient Mexicans knew so well, struggle depends on art to lift its voice.

[1] The official government number of dead was 26. Since then, Mexico has admitted to some 300. Other estimates put the number closer to 1,000.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Mexico City”