Most Albuquerque residents would be surprised to know that driving a mere five hours would take them to a place many consider comparable to Egypt’s Pyramids of Giza or Turkey’s Ephesus. It’s a truism that we tend to overlook the marvels in our own backyard, often putting off a visit for years, or becoming adventurous only when we have out-of-town guests. On the other hand, travelers from around the world come to see the extraordinary cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde; their diverse languages and exclamations of awe are heard every day among the ruins and throughout the Park’s installations.

If you have never been there, Mesa Verde, in southwestern Colorado deserves a weekend trip. A couple of days exploring the multi-storied Ancestral Puebloan ruins built within sandstone alcoves on the Colorado Plateau can be an exciting single destination or combined with visits to other nearby sites, such as the Ute Mountain Ute ruins—part of the same cultural heritage, separated by different designations of control—or the mysterious stone towers of Hovenweep.

Mesa Verde National Park sits atop an anvil-shaped mesa just off US Highway 160 between Durango and Cortez. You can reach US 160 via Chama, Bloomfield, Farmington or several alternative routes. Once you reach the turnoff, it’s another 15 miles of winding cliff-hugging road to the Park entrance. Early Spanish and Anglo explorers skirted the mesa; its height and dense vegetation kept its secrets hidden. Who could have imagined, in the 17th and 18th centuries that this great thrust of green was laced with interior canyons, beneath the rims of which great abandoned cities languished?

Today Mesa Verde has a campground and a single hotel, the very lovely Farview Lodge, with simple no-frill rooms that overlook a magical valley. Each room has a small balcony, and when the sun goes down in the late afternoon, or rises in the morning, stair steps of distant cliff reflect the rapidly changing light. On clear days Ship Rock is visible. No television sets disturb the evening quiet. You go to Mesa Verde not to check your email but to bathe your spirit.

Mule deer come up to the buildings, or leap in and out of the bush. From one of those balconies I once saw a large black bear rear up on his hind legs. Wild turkeys are frequently sighted at the lower elevations. Every few seasons, large wildfires consume terrain at Mesa Verde. A couple of times the flames have come within inches of the hotel. Miraculously, to date the Park’s installations have remained safe and when the fires die down new sites reveal themselves. Fire at Mesa Verde has simply been part of the natural renewal of the land. The Farview sometimes offers shoulder-season two nights for the price of one. Dinner in its dining room features a good version of standard cuisine combined with native beans and corn, staples to the people who once inhabited the alcoves.

Mesa Verde National Park was created in 1906 by President Theodore Roosevelt “to protect some of the best preserved cliff dwellings in the world.” In 1978 it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Ancestral Puebloans, familiar to us from the ruins they left at Chaco, Canyon de Chelly, and so many other places within an easy drive from Albuquerque, lived at Mesa Verde between A.D. 600 and 1300. Early inhabitants occupied pit houses and small mesa-top villages made of adobe. In the late 1190s they began to build the cliff dwellings for which the area is now known. As with most of the other sites, they were gone by 1500.

But unlike those other sites, we have continuity in terms of “where the people went.” The present-day Ute Mountain Utes trace their heritage back to ruins adjacent to, and of a piece with, those we can see at Mesa Verde. If you look at a map, just southeast of Cortez, Colorado, you will see the zigzag-bordered area called Mesa Verde National Park. Immediately adjoining it to the south is the much larger domain of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park, itself belonging to the Ute Mountain Indian Reservation, a vast territory that stretches west to the border with Utah and south into New Mexico. Arriving at today’s division took many decades and was rife with the usual examples of the White Man’s assault upon the Indians.

In line with its expansionist policies, the United States had periodically lopped off pieces of Ute territory, until the Indians retained a fraction of their ancestral lands. Finally, in 1911, the US government made one last attempt at total conquest. It is unusual that “Washington,” as the Utes then called anyone attempting to dislodge them, was not successful. In the 1960s a brilliant Ute elder named Chief Jack House proposed the establishment of Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park. This solution kept the Mancos canyons in native hands, while allowing tourists to visit the park’s backcountry ruins on tribal terms.

Mesa Verde National Park and the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park are studies in opposing philosophies of preservation and visitation. Mesa Verde is open all year round, and the regular modest National Park fees apply. Only Chapin Mesa is accessible in the winter, and facilities are also limited during the snowy winter months. Some 600,000 people visit each year, only about 10% of them ever venturing over to more remote Wetherill Mesa where, despite the popularity of the Park, you can sometimes find yourself almost alone in one of the alcoves.

A visitor center and museum, a team of well-trained rangers, limits on the numbers of people exploring some of the larger ruins at any one time, well-tended trails with good signage, and a host of procedures regulate all aspects of a Mesa Verde visit. Enormous and magnificent Cliff Palace is on Chapin Mesa. It is considered the Park’s crown jewel, appearing as if it has just been deserted minutes or hours before. Cliff Palace has become a place one may only access on a guided tour, complete with the usual forced pace and meaningless spiel. Wonder quickly turns to frustration.

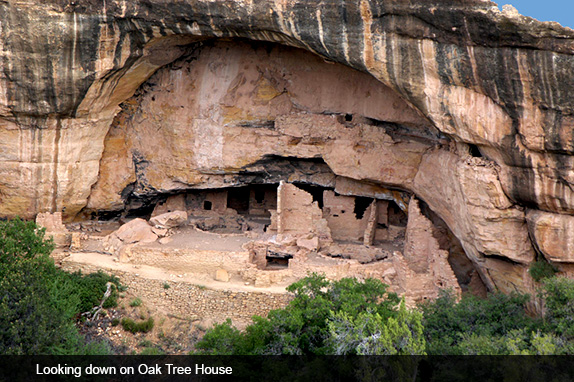

Wandering some of the “lesser” sites is much more satisfying. Far View, not in one of the alcoves but on the mesa top, is little visited and fascinating. Spruce Tree House, near the Park’s headquarters, is the only cliff dwelling accessible to wheelchairs, though I think it might be harrowing for all but the bravest. Balcony House is particularly interesting. In 2006 Mesa Verde celebrated its 100th anniversary as a national park. That summer limited small tours were offered to previously inaccessible ruins such as Oak Tree House and Mug House. They were special experiences for all sorts of reasons. I hope the Park will decide to make such visits available in the future.

A note about the Park’s small museum: it is well worth an hour or so. But I have long been disappointed that famed Fred Harvey architect Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter’s private collection of Navajo jewelry, willed to the institution and held in its basement, has never been put on display. Colter must have had a reason for entrusting her collection there. It’s a shame it has been kept from view. Most of our national parks must make do with vastly reduced budgets, only made worse in the current economic climate. This is a sad commentary on our priorities; the National Park system is among the best the country has to offer.

In contrast with Mesa Verde National Park, the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park has a very different view of how you preserve and show the cliff dwellings. You must call the Park to make a reservation for tours: half day $29, full day $48, and $12 extra per person if the tribe provides four-wheel drive transportation. Special tours to more remote areas are available for $60 per person, with a minimum of four people required. There are also special lower fees for groups of school children.

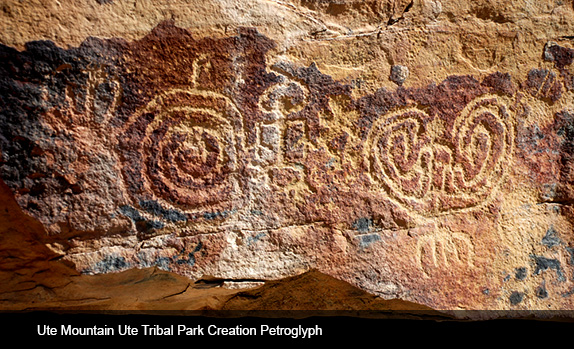

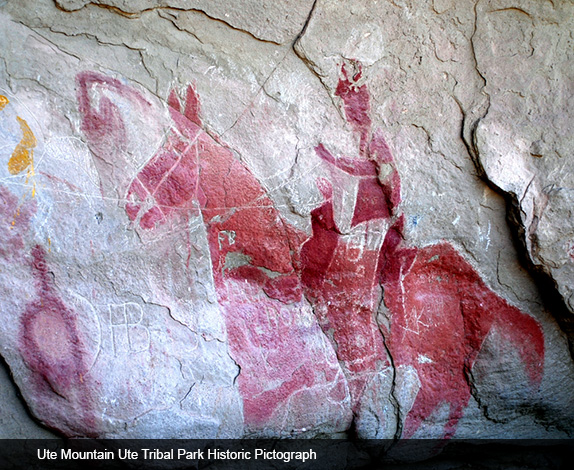

While more than half a million visit Mesa Verde each year, the Utes host approximately 3,000. While the ruins at Mesa Verde have been cleaned of every vestige of indigenous object, the Utes have left the pottery, corncobs, tools and other remnants used by their ancestors. And while tourists at Mesa Verde follow well-signed paved paths down into the cliff dwellings, on the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal lands we were accompanied by a guide eager to share with us the legacy of his forebears and to show us the examples of historic as well as prehistoric rock art that dot the canyons. Lion House, Porcupine House, and Tree House are some of the names the Ute Mountain Ute people have given the ruins in their canyons.

Both experiences are fascinating. Mesa Verde is probably set up so that visitors of all ages and abilities can access some part of the site. The Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park is more geared to the hardy backpacker, and the longer hikes into the more remote areas demand a fitness level many of us don’t have. Being taken even as far as I was able to go, though by a young Ute guide very generous with his explanations and stories, was an experience well worth the effort.

At both Mesa Verde and Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park, the “houses” or communities in the alcoves present sophisticated architectural solutions to problems of living, working, and defense. Beautifully joined walls of what once were structures several stories high, follow the curve of the natural concavity. Communal plazas and ceremonial kivas extend in front of the buildings. Above, sewn along the higher ledges, nestle perfect storage granaries. A detailed explanation of periods and building methods is beyond the scope of this piece. There are many excellent books about the cliff dwellings’ architecture.

The great “discoverer” (read: non-Indian who happened upon these ruins) of some of the major Houses at Mesa Verde and some of those in the Ute country as well, was Quaker farmer, self-proclaimed anthropologist and tourist guide Richard Wetherill. Wetherill’s parents, Benjamin and Marian, homesteaded near what is now the bucolic little village of Mancos, Colorado in 1879. They had come from the Midwest, and at a time when there was great distrust between settlers and Indians in the area, Benjamin gained Ute permission to graze his cattle on Ute land. Richard was the oldest living child, followed by Al, Anna, John, Clayton, and Winslow. Benjamin, Al, John, Clayton, and Anna’s husband Charlie Mason, all shared Richard’s fascination with the ruins in the canyons.

Richard, with his Quaker temperament, genuineness, and skill at mediation, also made friends among the local Navajos and Utes as well as with the other white settlers. During his life he owned several trading posts where he served as banker to the Navajo and encouraged the best of their art. One of these trading posts was at Chaco Canyon. But his life passion was always the cliff dwellings and other Ancestral Puebloan ruins. During and after his life, he was accused of being a vulgar pothunter, unschooled in the science required to excavate properly. But he loved the sites and knew that, as the word of their existence got out, real vandals would destroy them. His brother Al wrote that it was the brothers’ Quaker Inward Light that gave them the self-confidence to follow their intuition that these places must be saved and protected.

The country was young. The upper classes took steamships to Europe, visiting the great cities and spas of the day. No one was interested in the mysterious stone dwellings hidden in these remote southwestern canyons.

In the last decades of the 19th and first of the 20th centuries, the US was also witnessing the development of new disciplines: anthropology and archaeology. Turfs were established and jealously guarded. No one had any use for a Quaker cowboy with no formal archaeological training who so desperately tried to interest the Smithsonian and Peabody museums in exploring and preserving ruins only he and a few others had seen.

The Wetherill brothers spent the last decade of the 19th century investigating ruin after ruin. By 1890 they and their associates had visited 180 different sites in and around the canyons. (By 1935, the Park Service and University of Colorado archeologists had found 4,000. Today many more have been unearthed.)

Richard claimed to have discovered Mesa Verde’s Cliff Palace in 1888, although initials, names and dates scratched into the rock show that other adventurers preceded him. But it was Wetherill who dug at many of these sites, removing tons of objects, burials and other valuables. The Wetherill family farm had its own private collections, and Richard is known to have sold large quantities at several Worlds Fairs and to other private collectors. He wrote desperate letters to the Smithsonian, pleading for experts to come and teach him how to dig correctly. He never received the response he—or the sites—deserved. Interestingly, General John Wesley Powell, of Grand Canyon fame, was one of the men who brushed Wetherill off.

As the 20th century dawned, however, Richard Wetherill did receive attention from the other scholars and field workers staking claims to the prehistory of the US American Southwest. It wasn’t the attention he wanted. They resented his presence and did everything possible to stop him from following his passion. They might have teamed up with him, reaping his hands-on knowledge and benefitting from his long experience. Sadly, academic disciplines don’t often make such allowances. (One notable exception is the field of Mayan research, where experts in many disciplines have invited the contributions of adventurers, native peoples, and even children, thereby vastly enriching their research and solving problems that might otherwise have remained insoluble).

Richard Wetherill couldn’t continue to work at Mesa Verde and was barred from working at Chaco. During his life, he was ostracized by almost every expert in Southwest archaeology. He died at the age of 52, in a shooting that has never been fully explained. But today Richard Wetherill’s role has been reevaluated. The first volume published by Mesa Verde National Park in celebration of its 2006 centennial is a book called The Wetherills: Friends of Mesa Verde. It vindicates Richard’s name and legacy, and not only offers a fascinating look at an important frontier family, but allows us to understand an astonishing chapter in our nation’s efforts to decipher, care for, and learn from her Ancestral Puebloan past.

I highly recommend The Wetherills: Friends of Mesa Verde. It’s a fascinating read. And I highly recommend a visit—or two, or three—to Mesa Verde National Park and to the Ute Mountain Ute Tribal Park, each embodying a unique way of preserving and showing these treasures.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Mesa Verde”