Geographically and in terms of population, Uruguay is a tiny Latin American country wedged between its giant neighbors Brazil and Argentina. On the southern continent it is only larger than Suriname. Three point three million people call it home. In contrast to its physical size and population, it is large in history and lucidity. We could learn a great deal from its current history. In this second part of a series, I want to talk about the country’s sustainable energy plan.

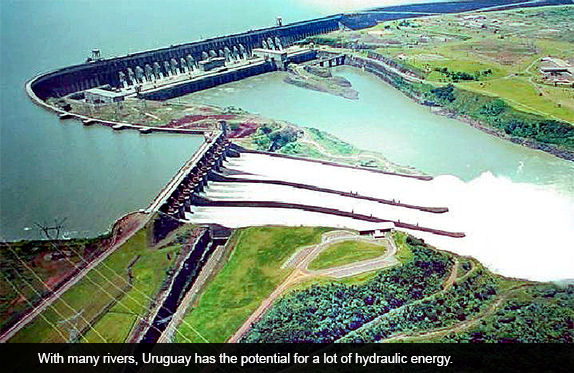

With many powerful rivers, Uruguay is rich in hydraulic energy. As an agricultural country, biomass is abundant. Wind is another plentiful source. And, as important as all these, a progressive government determined to meet the needs of its constituents has demonstrated the will and designed the priorities needed to make the country a leader in energy transformation.

Like many parts of the world, Uruguay is vulnerable to global warming and climate change. A hole in the ozone layer lies precisely above this part of the world, and so, as a destination renowned for its beaches, intense sunlight can nevertheless bring danger. Uruguayans are advised to stay away from the beach between ten in the morning and four in the afternoon, but I’ve never noticed anyone taking that advice very seriously.

Uruguayans also understand that climate change is a global problem and its solution the responsibility of peoples everywhere. On my most recent trip to the country, the words of the Philippine lead negotiator to the UN Summit on Climate held in Warsaw in November 2013 were fresh in my memory. After making a fervent plea for governments to reverse or at least slow global warming, Yeb Sano said: “In solidarity with my countrymen who are struggling to find food back home and with my brother who has not had food for the last three days . . . I will now commence a voluntary fast for the climate. I will refrain from eating food during this COP until a meaningful outcome is in sight.” The image of Sano as he spoke those words—his face a mask of pain while the faces of other delegates seemed mostly unaffected—still throbbed behind my eyes. It superimposed itself upon images of the devastating storms we have experienced through the world, as climate change moves from ominous prediction to palpable problem.

As we know, there was no meaningful outcome, at this last summit or any of the previous ones. The wealthiest governments, immersed in ignorance and greed, keep on talking without agreement. The poorest plead for their lives. Uruguay, meanwhile, has taken it upon itself to do its part in reducing non-sustainable energy consumption, lowering carbon dioxide levels, and committing itself to success in this important area.

With a progressive government in place, in 2005 the country designed a comprehensive but viable energy policy. Broad, multi-aspect, and extremely detailed, it outlines goals to be met from its inception through 2030. It is on track to meet those goals; by the end of 2015—two years from now—Uruguay, including all automobiles, will run on 50% renewable energy sources.

In determining its energy needs, those charged with writing this policy considered sustainability, public health, and national values, as well as resources and cost. Prohibition of nuclear energy, for example, is written into the country’s constitution: not only building nuclear plants but also importing atomic energy from nearby countries such as Brazil (the latter is hard to completely control, since there is no way of guaranteeing the source of the energy imported from the larger country). Several years ago, I attended a public discussion on nuclear energy at Uruguay’s University of the Republic. Every single testimony and report made it absolutely clear that the country will not go down the dangerous nuclear road.

Uruguay’s energy plan lists six general themes to be taken into account.

The first is geopolitical, meaning access to primary energy sources. Ninety two percent of the world’s energy consumption comes from oil, natural gas, carbon and uranium. These exist disproportionately and are rapidly being depleted.

The second is technological. It’s not enough to possess or import energy in crude form. One must also have and be able to employ the technology needed to transform that energy into secondary products.

The third is economic. Growing consumption throughout the developed and developing worlds, means that energy in its primary form as well as the technology necessary to transform it are every day more costly. Oil extraction is big business with powerful influence. Here in the United States we have only to think of the harm wrought when British Petroleum’s Deep Water Horizon extraction platform exploded in 2006, spilling untold gallons of crude into the Gulf. The devastation to the coastal environment, hundreds of species of birds and animals, the fishing industry and human health has never been fully disclosed, but those living with the tragedy know its impact.

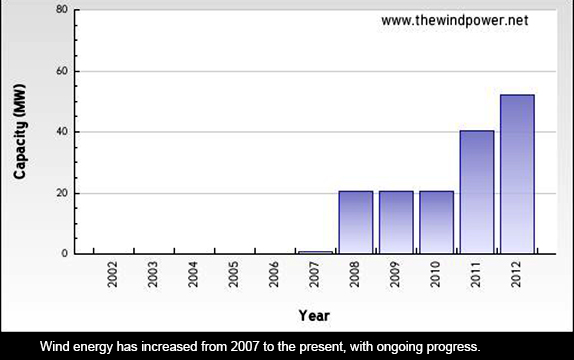

At present there are ten wind farms throughout the country, built in places where this resource is easiest to capture. These range from small single-turbine farms such as Agroland and Engraw (productions ranging from 450 to 1,800 kilowatts), to Florida with 21, Nuevo Manantial with 16, and Minas with 14. El Liberator has 44 turbines in operation and produces 66,000 kilowatts of energy.

The fourth area looks at the ethical side of the problem. Since 92% of the energy consumed throughout the world is not renewable, in only two centuries humanity has depleted what it took nature millions of years to produce. It is more than obvious that this calls for a new level of responsibility—to the sustainability of life as we know it, and to our children and grandchildren.

This means that the population must be educated to save energy as well. In Uruguay, this education has been quite successful. There is a high level of consciousness at the personal level. When governmental policy and corporate culture are so clearly a part of the picture, individuals are more than willing to do their part. One of the things I find frustrating in the United States is that public service announcements so often urge us to do our part when neither government nor industry are doing theirs.

I am tired of being urged to save the economy by spending money I don’t have, when crooked banks and corporations are deemed “too big to fail.” Or to turn off my lights when big companies receive tax breaks even as they waste obscene amounts of energy and foul earth and air in the process.

The fifth area is environmental. Energy production and use are responsible for the emission of carbon dioxide that is killing off our capacity to live and reproduce. Sixty percent of all carbon dioxide emissions worldwide are generated through the production and use of non-renewable energy.

And the sixth area is social. Energy access throughout the world is vastly unequal, both between countries and within a single country. Great numbers of human beings lack adequate access to energy. Approximately 1.7 billion people in the world today live as if they were in the eighteenth century. Without access to electricity, they are reduced to burning bits of timber they find nearby in order to try to meet their energy needs.

The Uruguayan energy plan is posited on the belief that a rational energy policy can become a vital instrument for developing the country and at the same time promote social equality. Following the in-depth discussion begun in 2005, in 2008 the Direction of National Energy and Technology presented its proposal to the executive branch of government. Its strategy defined short-term goals to be achieved in five years, medium-term goals to be achieved in ten to fifteen, and long-term goals to be completed in 20 years or more. The proposal included lines of action necessary to meeting those goals, as well as an ongoing analysis of the situation in the country, the region and the world.

Because of its importance and complexity, all the political parties and poles of influence had to be on board. Although small, Uruguay like most nations has groups ranging from extreme left to extreme right. The Frente Amplio (Broad Front, currently in power) has so far earned enough popular support and been able to bring even dissenting constituencies along. Despite periodic pressures exerted by the private sector and/or international and regional bodies and lending institutions, Uruguay has been able to move ahead with this ambitious plan.

By 2015, when the short-term goals must be met, renewable energy sources (wind, water and biomass) will have reached 15% of the country’s energy generation. At least 30% of the country’s agro-industrial and urban residue will be used to produce energy, thus transforming a passive byproduct into an active energy source. New technologies will have reduced the consumption of oil for transportation by 15% as well. By 2015 100% of the population will have access to electricity, and a culture of energy efficiency will have permeated society.

By 2030, Uruguay hopes to be a leader in sustainable energy production and consumption. From 2010 to 2030 its energy policy will have saved it at least ten billion pesos. It is counting on similar efforts by other countries in the region. If it continues as it has to date, there is every reason to believe this small country will have been able to achieve what so many larger, richer, and more powerful nations only argue about.

With only enough space to offer a very rough outline of Uruguay’s energy plan and goals, readers may have a number of legitimate questions. The Internet is full of articles about all aspects and phases of the country’s energy policy and how its goals are being met. There are photos and graphs, scholarly papers and partisan reports. Those like myself, who have been close to the Uruguayan people for decades and followed their history from their liberation from Portugal and Spain through early advances in legal freedoms, the cruelty of the Dirty Wars of the 1970s, restoration of democracy and finally the installation of a Broad Front coalition of left and center-left parties and groups, feel confident the goal can be achieved.

After years of steady work, the Broad Front won the 2004 national elections with 51.7% of the popular vote, 52 out of 99 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 17 out of 31 in the Senate. Its first president, Tabaré Vázquez, assumed office in 2005. The Front retained its majority and the presidency in the 2009 election, with the installation of José Mujica. This former Left guerrilla leader has gone further than his predecessor in strengthening human rights and equality. As everywhere, there are complaints about Mujica not doing enough or doing some things wrong. There is always room for improvement.

But in the past several years, Uruguay has raised health providers’ and teachers’ salaries by three and two and a half times respectively. It has initiated a number of successful programs designed to lift people out of poverty. It has legalized abortion, passed the third federal marriage equality law in the Americas (after Canada and Argentina), legalized marijuana in an effort to deal a deathblow to the drug trade, and is solving its energy problem with a determination and creativity evident in few other countries. Mujica himself refused to occupy the presidential mansion, preferring to remain in the working class home in a poor neighborhood of the city where he’s lived all his life. He drives a beat-up Volkswagen Beetle and flies economy class. But this president says those who consider him poor fail to understand the meaning of wealth: “My lifestyle is a consequence of my wounds,” he says, “I am shaped by my history. There have been years when I would have been happy just to have a mattress,” referring to the 14 he endured in a military prison, most of them in dungeon-like conditions.

From the time of his inauguration, Mujica has taken only 10% of his salary, designating the other 90% to a project called Plan Juntos (Plan Together), through which the government provides the construction materials and know-how to people wishing to build their own homes. With this sort of example, success through a well thought-out energy plan seems well within reach.

(Images: Solar panels by Oregon Department of Transportation; Sun on horizon by Jaan-Cornelius K; Wind Turbine by Random Photos)

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Lessons From Uruguay Part 2”