Because my son and his family live in Uruguay, over the past two decades I have traveled there on an average of once a year. I always come home wishing we US Americans possessed a fraction of the attention to history, global consciousness, compassion, determination to improve our quality of life, and capacity for issue-based political organization I observe there.

Native Charrúas inhabited the territory before the European conquest but were decimated by colonization and today are a slowly-retrieved memory. Although many Uruguayans have indigenous blood, the population is largely Caucasian with a miniscule number of people of African descent. Large Spanish and Italian immigrations took place from the late 19th into the early-to-mid-20th centuries, and their cultures are part of the national fabric. People drink mate, a bitter herb infused in hot water. They walk around carrying the traditional gourd with its silver straw and a thermos with extra water. Adding hot water and passing the gourd to a friend is a common ritual. Looking toward the sky in the Southern Hemisphere, one has to get accustomed to watching the moon move in the opposite direction of how it does here, and seeing a different configuration of planets.

Uruguay’s road has not been easy. After a forward-looking period in the early twentieth century, during which the country was a continental leader in social equality, legal rights, protection for women, and peaceful coexistence, policies of interference and control on the part of the United States as well as the pandering of a local oligarchy created social unrest. An underground organization known as the Movimiento de liberation nacional - Tupamaros gained in energy and popularity, and was soon put down by the installation of a brutal dictatorship.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, the country suffered its version of the Dirty Wars then assaulting the Southern Cone. As in other parts of Latin America, imprisonment and torture were routine. Many people were forced into exile. Disappearance was a particularly horrendous mode of state terrorism, in which hundreds of people were simply disappeared by military and paramilitary forces, never to be seen again. Their families continue to demand to know their whereabouts and be able to lay claim to their bodies. The Association of Families of the Disappeared is an important organization fighting for human rights on all fronts.

It took courage and unity in the face of almost impossible odds for the dictatorship to be defeated. In 1984 a bourgeois democracy took over, and in 2004 a coalition of progressive parties that had come together in a Broad Front (Frente Amplio) won the presidential and legislative elections. Today José Mujica, an ex-Tupamaro guerrilla leader, is president. He has refused the trappings of bourgeois presidents, shunning the presidential mansion for his old family home in a working class section of the capital. He is famously casual in his dress. He gives 90% of his salary to a project designed to help those living in poverty to build their own homes.

Not every public official, of course, emulates Mujica’s simple lifestyle or devotion to the poor. But there are many who are taking advantage of the opportunity to serve in the deepest sense of that word. Healthcare and public education are two areas that have received special attention and have become examples even for countries with greater resources.

Healthcare, so prominent on our current agenda in the United States, is deservedly considered first-rate in Uruguay. Its most common form, the mutualista that is available to anyone who works, is simplified and straightforward. There is no deductible, no lifetime cap, and no complicated terms to decipher. Other health plans are available, with a variety of coverage options. And public hospitals offer decent attention. The bottom line is that no one goes uncovered.

Uruguayan healthcare, of course, has had its history. During the early part of the twentieth century it was considered outstanding, for the high level of medical personnel as well as for its ample coverage. During the dictatorship, from 1973 to 1985, standards of care in public hospitals and clinics were adversely affected by severe budget cuts. Now, with a progressive government in place, healthcare has once again become something Uruguayans can be proud of. Its quality and availability are exemplary.

Public education follows a similar pattern. It has always been important and highly rated. Even in 1985, the country had the highest literacy rate in Latin America, at 96%. When my grandchildren went to school in Minneapolis during their father’s sabbatical year, they were threatened with having to repeat the term when they returned to Uruguay; so much poorer was public education here than there. Only by studying hard and passing a series of exams were they able to save that year.

Education is free through the university level. The only public university in the country, the University of the Republic, was founded in 1849. In time it evolved toward the characteristics stipulated by the University Reform Movement that took place in Cordoba, Argentina, in 1918. That Movement established the guidelines for a university that would meet the needs of its community. University autonomy and co-governance (resting on the shoulders of professors, students and alumni) are important. There is no such thing as tenure, and these three sectors have the ability to fire or retain teachers and even the institution’s president and other administrative leaders. Today many Latin American universities have returned to the US model, while Uruguay’s University of the Republic is working to maintain the centerpieces of university reform, updating them to meet the challenges of the 21st century.

Public education also suffered terribly under military rule. Progressive teachers were murdered, imprisoned, or forced into exile. Curricula were altered. Teachers and professors who came home when the dictatorship fell have had to work hard to make up time, both personally and professionally.

Today the Uruguayan university is once again a place of quality and outreach, serving society and educating for the future. A university education, once only obtainable in the capital, now exists nationwide. Over the past four years, campuses have opened in six other states. Each of these offers disciplines unique to the needs of its particular location; it is not some “lesser” version of the main campus, but a school that can attract important talent and educate for the community. Qualified professors from around the world are eager to go to Uruguay to participate in this sort of educational experience.

Uruguay is the only country to so far have implemented the “One Laptop Per Child” initiative. Every primary and high school student is given his or her own solar-powered computer. Peasant families with ten children have ten such computers. Parents become involved as well, and this program, called Plan Ceibal in Uruguay, stimulates learning, creativity, and connection.

Visiting my daughter-in-law’s father, who was the University of the Republic’s Dean of Medicine when the dictatorship took power, I heard him lament certain downgrades in public high school education. Some of the emphasis on testing we have experienced here has made its dangerous way there. Pablo remembered his own youth, in which his high school teachers were experts in their fields. Their salaries were on a par with that of a doctor or banker. As has been true elsewhere, over the years teachers’ salaries have gone down and the profession has attracted less capable people. On our recent trip I also heard about some of the more conservative members of Congress suggesting that university curricula be approved by parliament. I don’t believe such a suggestion has a chance of being realized. But it is clear that in Uruguay, as elsewhere, public education must be defended, preserved and protected.

The tiny Latin American country, wedged between Argentina to its west and Brazil to its north and east, and with a coastline of popular beaches along the sea-like La Plata River and the Atlantic Ocean, is home to 3.3 million people. Almost two-thirds of them live in the capital, Montevideo, with medium-sized populations scattered in some thirty towns and many still working the land. Perhaps this small population has made such interesting social initiatives easier to implement.

Among the country’s main sources of revenue are cattle-growing, rice, and timber. Uruguayan beef and wool compete well with that from Argentina. Dairy products are wholesome, produce as yet untainted by genetic modification. Food tastes like food.

Most people don’t know that Uruguay has the third-highest rice productivity in the world—an average of 8 tons per hectare of dry paddy rice in the last 5 years—thanks to a unique system that has triggered a 25% gain in productivity. Given the need to produce an estimated 116 million additional tons of rice by 2035 to meet the growing global demand, the country has adopted a well-integrated structure that includes vertical integration and transparency among farmers, millers, researchers and the government, well-defined rules on rice quality standards, active participation of farmers and millers in research goals, and an agreement on price. In Uruguay, only 580 rice farmers are cultivating some 180,000 hectares of irrigated rice. Around 95% is exported, with key markets in Iran, Iraq, Brazil, and Peru.

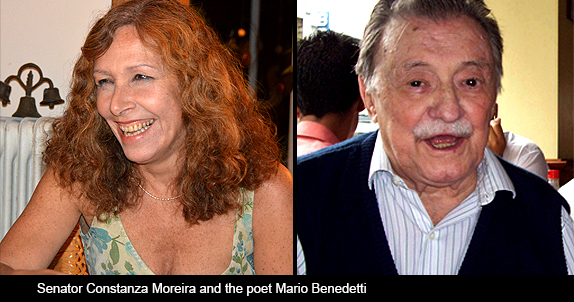

But it isn’t only rice and beef, timber and dairy products that enrich the country. Uruguay has a plethora of brilliant minds and outstanding artistic talents, statesmen and women of high caliber, and scientists of note. US readers are familiar with Eduardo Galeano, one of the greatest among many great contemporary Latin American writers. Less well known here is the poetry of Mario Benedetti, although that gap is now being filled by the excellent translations of Louise Popkin in the recent collection Witness. Singer-songwriter Daniel Viglietti is known and loved internationally. And on this recent trip I met Constanza Moreira, the firebrand senator who helped write several of her country’s recent progressive laws and has surprised people by postulating herself as a presidential candidate in the next election.

In a second installment I will talk about Uruguay’s energy policy, on track to achieve energy independence in not too many years. In a third I will detail some of the great new laws passed recently. And in a fourth I will talk about work.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Lessons from Uruguay Part 1”