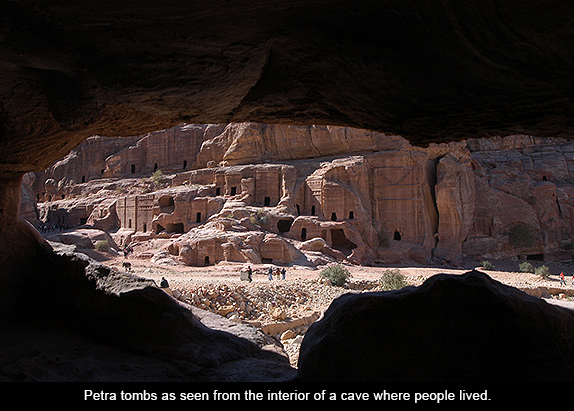

It was 2004. I was taking one of my grandchildren to the Museum of Natural History in New York. Along with its permanent collections, the great museum always showcases at least one traveling exhibit that makes viewing the huge whale skeleton or dinosaur bones worth the trip. This time it was Petra, once the capital city of the Nabateans, a long hidden valley of royal tombs dating to approximately 300 years before our era.

Up to that moment I hadn’t given Petra much thought. I might not have been aware of its existence. But that day, hand in hand with my 8-year-old grandson, its relics and photos captivated me completely. One image, a pristine period drawing, showed the famous scene at the end of the narrow slot canyon carved from rock called the siq, at the point where the immense walls fall away and the glowing pink face of what is now called The Treasury appears. A square stone mask, simple in its stylized features, also lodged itself in my consciousness.

That day I vowed I would visit Petra. I had no idea how to arrange such a trip. The United States had already invaded Iraq for the second time, and travel to the Middle East wasn’t high on most people’s lists. When I looked on line, the only tours I could find were those to religious sites, including brief forays into Jordan (I learned its full name was the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan). Without any luck among US travel companies, I wondered if Jordan itself might have one willing to design the trip I wanted.

That was the beginning of the magic. Petra Moon Travel, with its office in the small village by the ruin, turned out to be everything I could have hoped for and more. Via email, the person who responded to my inquiry helped me set up exactly the trip I wanted. When we’d agreed on every detail, and I asked for a secure site to which I could send my credit card number, I was told: “Oh we wouldn’t think of charging you before you make the trip. How would we know if you were satisfied? Just bring the money with you.”

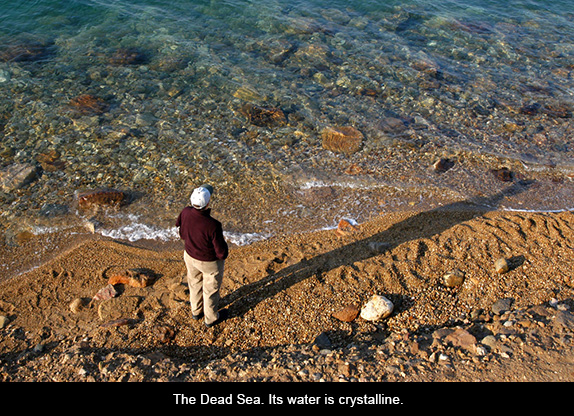

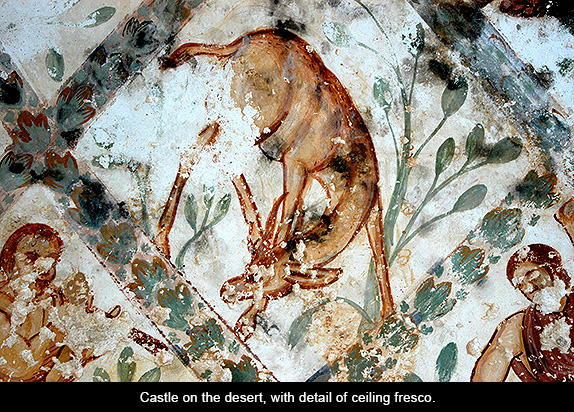

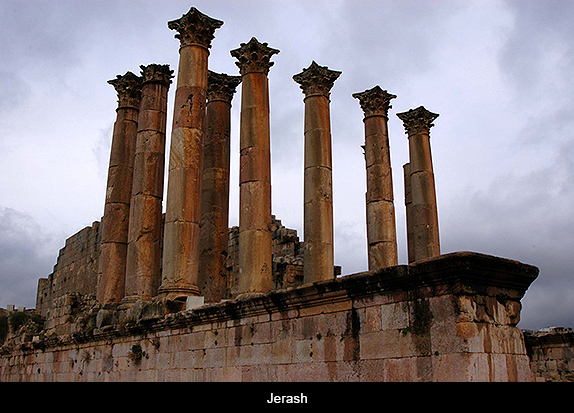

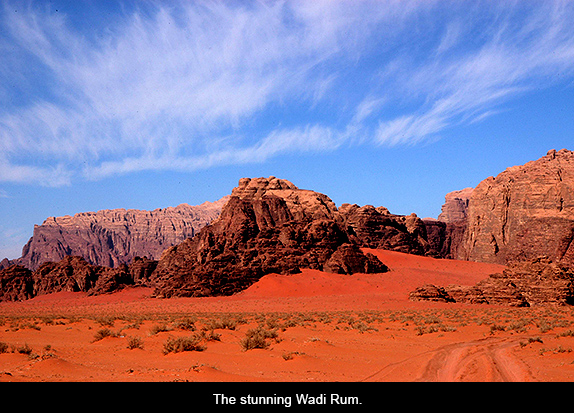

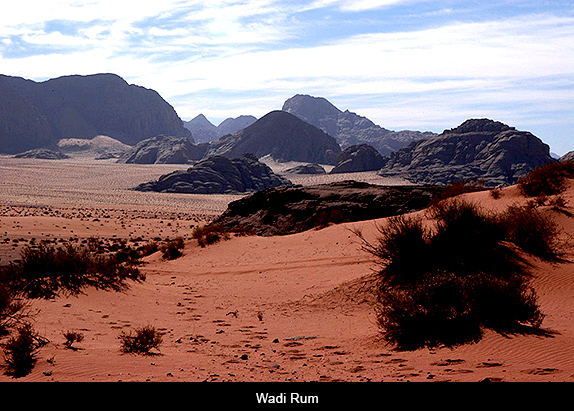

And so, in December of that year, my partner and I flew to Amman, where our English-speaking guide met us at the airport, and off we went. Jordan is much more than Petra, of course, and we planned to see as much as possible: the capital city, some of the castles on the desert, other extraordinary ancient sites such as Jerash and Um al-Jimal, the Dead Sea, and the stunning landscape of the Wadi Rum. At Petra Moon’s insistence, we even visited the spot on the Jordan River where John is said to have baptized Jesus (on the Israeli side of the river another spot is advertised). And I’d managed to get Petra Moon to include a couple of women’s cooperatives.

Perhaps the Jordanian personality with whom US feminists are most familiar, is Lisa Najeeb Halaby, an American-born urban planner and activist for women’s rights who married that country’s King Hussein on June 15, 1978. She became the first American-born queen of an Arab nation, taking the name Noor al-Hussein or Light of Hussein. She and King Hussein married in a traditional Islamic ceremony at the Zaharan Palace, where Queen Noor was the only woman present. During his reign and since his death, she paid a great deal of attention to Jordanian women’s lives and created projects designed to give them educational and work opportunities.

I knew that King Hussein had been a force for equilibrium in the Middle East, and that his son, the current ruler Abdullah II, has largely continued his legacy. Although women in Jordan fare better than they do in many Islamic countries, they can use all the help they can get. One morning, reading the front page of The Jordan Times (the country’s English language newspaper), I couldn’t help but notice the juxtaposition of two featured articles. One documented an “honor killing,” in which a woman’s jealous brother-in-law had stabbed her to death rather than accept her intention to divorce his brother for another man. The other congratulated a class of 18 women who had just graduated as electricians.

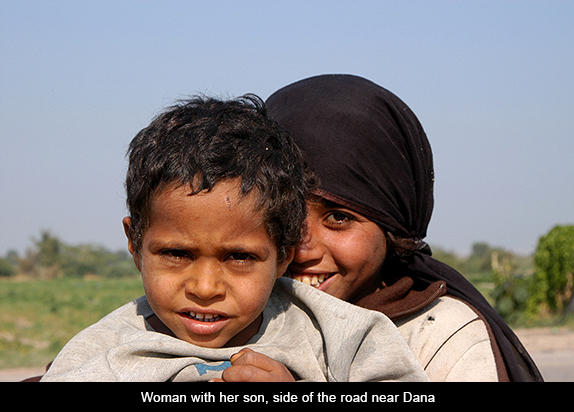

Wherever we went in Jordan, people were friendly and welcoming. On several occasions I noticed particularly honest relations with tourists. Up very early one morning, in the village of Petra, I was surprised to see silver jewelry and other items lying unattended on rugs spread out on the sidewalk. I wondered at the absolute trust displayed, and was told no one would dare steal anything “for fear of having his hands cut off!”

On another occasion, when I’d left several dozen post cards at a small post office to be stamped and mailed, the man on duty insisted I come back that afternoon so he could show me that he had indeed used the money I’d given him to affix a stamp to each card. But without doubt the most impressive display of this sort of honesty was our tour company’s refusal to accept our money prior to our arrival. Nor would they accept it once there, not until the very last day. They really did want to make sure we were satisfied with what they had arranged for us.

Although the magic accompanied us throughout trip, and there are many places I will remember for a very long time, Petra was the highlight. We had planned three full days at the enormous site, and still found it wasn’t enough. When we told the people at Petra Moon we wanted to skip our day at the beach they’d arranged at the very end of our visit, and spend another in Petra, they accommodated us without the suggestion of extra cost.

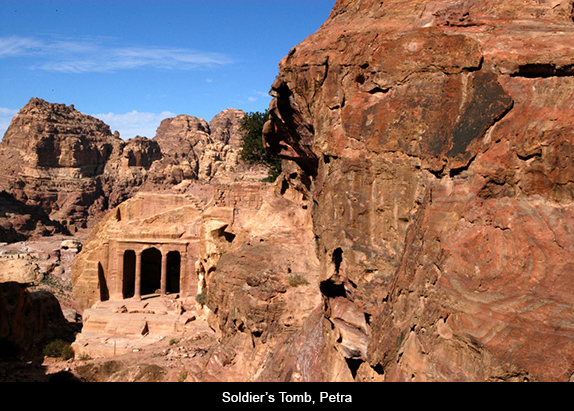

Situated in a relatively narrow valley behind massive walls of rock, Petra was unknown to the outside world until 1812. A Swiss explorer named Johann Ludwig Burckhardt heard about its existence and, disguised in Bedouin dress hiked to the far side of those walls. It’s hard to imagine his astonishment when, emerging from the narrow siq he caught his first glimpse of the immense rose-colored tombs carved into the rock face. Early explorers referred to Petra as “a rose colored city half as old as time.”

The Nabataeans had water. They didn’t have to conquer to build their extraordinary kingdom. They simply devised a system of cisterns and waterways that allowed them to share the precious liquid with the camel trains bringing spices and fabric, earthenware and tools from halfway around the known world. In exchange for water, they took a percentage of the goods carried by each train. Thus, Roman, Greek, and Byzantine influences can be seen at the site.

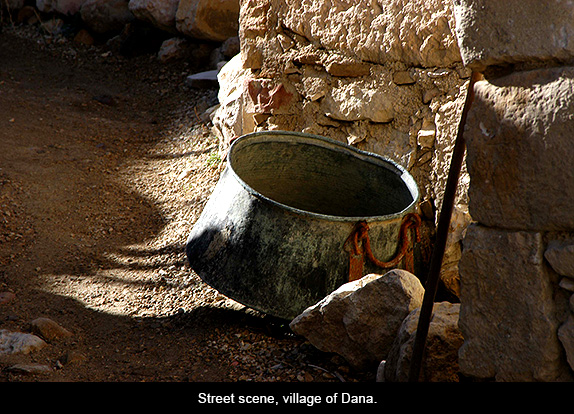

Tourism accounts for 10% to 12% of Jordan’s Gross National Product, and a good amount of that surely comes from visitors to Petra. But the country also offers the beautiful beaches at Aqaba and the Dead Sea, eco-tourism at nature reserves such as Dana, Shaumari, and Azraq, the fascinating castles on the desert (many of them old hunting lodges), and the rich cultural life of Amman. The Wadi Rum, with its purple, orange and red sands and nomadic Bedouin tents, is a world unto itself.

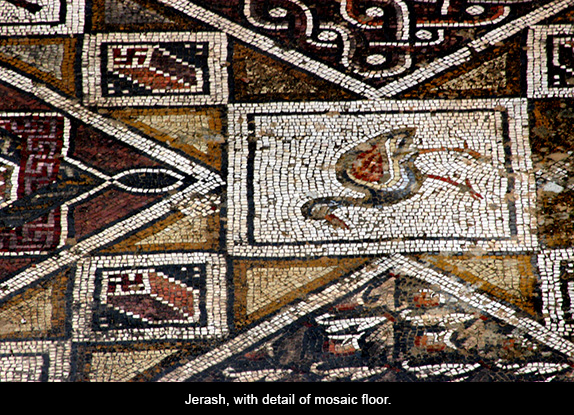

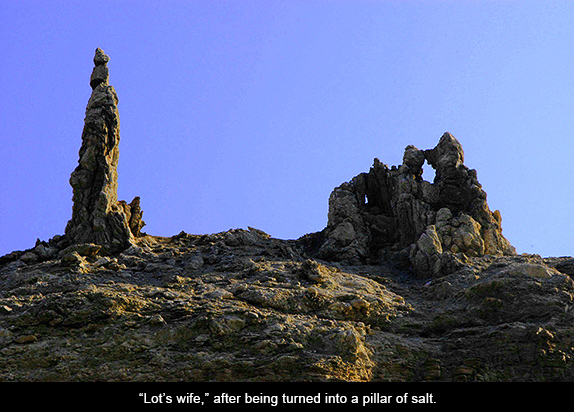

And then there are the destinations frequented by religious tourists, such as Mt. Nebo, Bethabara (where John the Baptist is believed to have conducted part of his ministry), and the mosaic city of Madaba. We were driving through the countryside one day when our guide stopped to point out “Lot’s wife. Look, that’s where she become a pillar of salt.” I laughed and asked if that wasn’t a fable. “No,” he assured me, “It’s history.”

I was not surprised to learn that a good part of Jordan’s income also comes from those who go there for health reasons; the country is known for its excellent medical attention, for its citizens as well as those from elsewhere. Jordan is classified by the World Bank as a country of “upper-middle income.” Since 2005, its economy has grown at an average rate of 4.3% per year. Still, approximately 13% of the population lives on less than $3 US a day.

Although Jordan is a constitutional monarchy, the king holds broad executive and legislative powers. Since 2010 it has enjoyed advanced status with the European Union, and has long been friendly to the United States. At the same time, it has been very supportive of the tens of thousands of Palestinian refugees flowing into the country as a result of Israel’s wars and ongoing harassment of the Palestinian people, offering those who wish to have it Jordanian citizenship. In recent years, the worldwide economic recession, as well as the general turmoil in the Middle East, have inevitably affected the country’s economy.

Petra was everything I dreamed when I discovered it in the exhibition halls of New York’s Museum of Natural History. And Jordan was a surprise. The Jordan Rift Valley, separating the country from Israel and the Palestinian Territories, cradles a land rich with multiple cultures, ancient architecture and art, and people looking to the future.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Jordan”