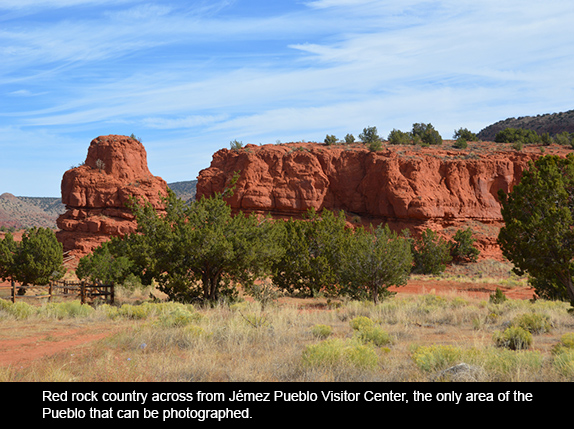

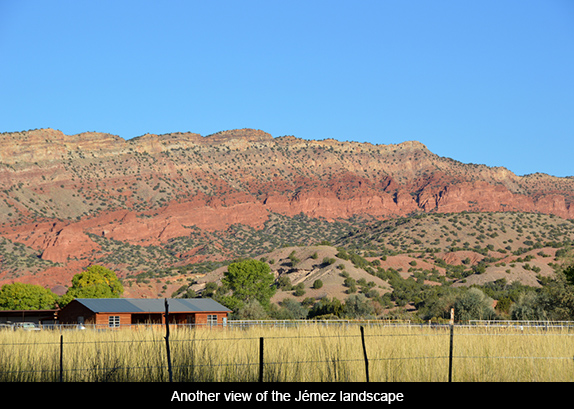

The Jémez Mountains, an hour to an hour and a half drive northwest of Albuquerque, is without doubt one of New Mexico’s most beautiful areas. Almost from the moment you turn off NM Highway #505 at the tiny village of San Ysidro, varicolored rock formations rise on either side of Highway #4: blood-sausage browns, deep reds, purples, pale tans and pinks, whispers of green and gold. Varying altitudes produce variety in vegetation, with large groves of Ponderosa Pine and Aspen, among other trees. Fall brings the heart-stopping turning of the leaves to the quaking gold we also see in other parts of the state.

Jémez Pueblo is (wisely) closed to the public except on feast days, but its Walatowa Visitor Center and worthwhile museum are open daily. At the latter you can see beautiful examples of Pecos pottery as well as that from Jémez itself. Today Jémez is known for its unique storyteller dolls. The Pueblo looks prosperous, with many new homes and new roofs on many of the old. Beautiful schools, a clinic, community center and other public buildings abound. Without having chosen to go the casino route, I wondered what the major sources of Pueblo income are.

Jémez Historic Site (formerly Jémez National Monument) is a beautiful semi-restored ruin of a 14th century Indian community and 17th century colonial church located right in the middle of Jémez Springs. Bandelier National Monument and Tsankawi are not far to the east. The Gilman Tunnels, overlooking the Guadalupe River, are on nearby State Route #485. And 100-foot high Jémez Falls can be reached by a short hike from Highway #4.

In the midst of all this bounty, the small town of Jémez Springs offers lodging, food, spas and galleries. It is a friendly place, although there is a paucity of decent restaurants. I can remember years ago eating at The Laughing Lizard, a good eatery unfortunately no longer in business. Los Ojos Restaurant and Saloon is known for its steaks and atmosphere. It is definitely the place to be on a Saturday night, but we found its food just barely acceptable.

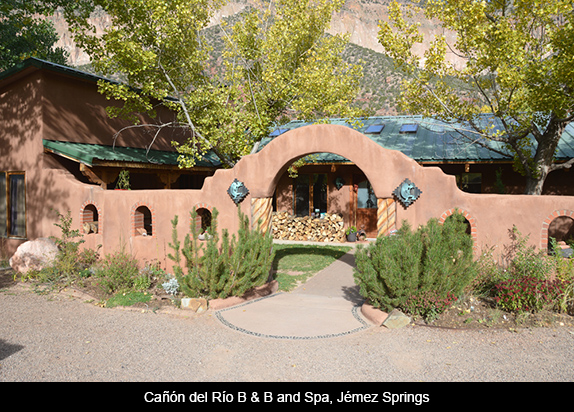

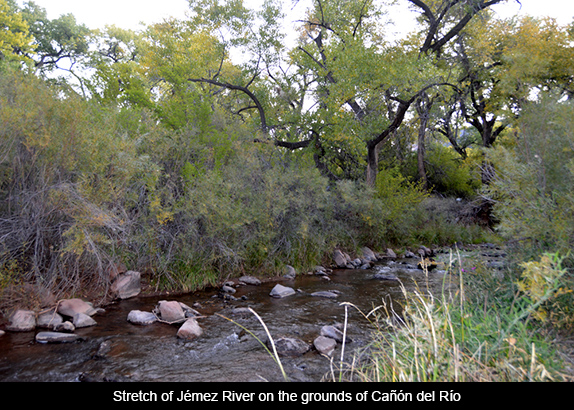

On the other hand, I cannot praise Cañón del Río enough. This is the absolutely perfect B & B where we chose to spend the night. It surpassed every expectation. The grounds are magical, rooms supremely comfortable, and the included gourmet breakfast may just be the best I’ve ever had. Dania, our gracious host, told us they offer special rates for retreats, especially during the winter months. We didn’t indulge in a massage or other spa service, but another guest who did assured us the massage had been first rate.

There is evidence of there having been human life in the Jémez Valley since 2,500 years before our era. Ancestors of the Jémez Indians lived here, and in 1680 took part in the Pueblo Rebellion. The Spanish, who had come to conquer in 1540, retook the territory in 1692, but the Jémez refused to surrender for two more years. Mining surged during the 1800s, followed by sheep herding. But settlement didn’t really take root until the early years of the twentieth century. Lumbering became important in the 1920s and ‘30s, at which time a short railway line was built to bring logs down from the surrounding mesas. Recreation and tourism became major activities around 1940.

Religious orders soon bought land in Jémez Springs. Catholic Servants of the Paraclete and Handmaids of the Precious Blood arrived in 1947, and together own a major percentage of the village land. Presbyterian and Buddhist holdings are also in evidence. The latter operates hot springs where visitors and locals can come and soak. There are three or four hot spring establishments with clean and welcoming facilities. A paved pathway paralleling the main street was built in 2009. In 1995 Jémez Springs was named an All-American City, one of the smallest urban entities in the nation to receive the honor.

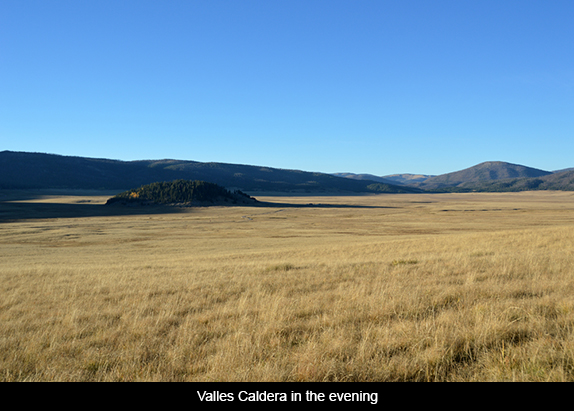

This area’s landscape of varicolored rock, a pristine river, waterfalls, and other natural features is enough to attract visitors from around the world, but now we also have Valles Caldera, a unique expanse of volcanic crater that quite literally takes your breath away. We used to call it Valle Grande (Big Valley) because of its size. I remember years back driving along Highway #4 and gazing out into the vastness of its undulating expanse rimmed with hills that looked in the distance like tiny rises of green. A lone house seemed lost and lonely.

In 2,000, the US Department of Agriculture purchased the immense site for 101 million dollars. It is one of the largest volcanic craters in the world. After several years of organization, it was designated Valles Caldera National Preserve and opened to the public, offering free self-guided as well as inexpensive guided hikes, a backcountry shuttle system, and experiences in earth skill gathering, an Elk Festival, a twilight mountain bike ride, a Storytelling Jamboree and more. Hunting and fishing are permitted in season, and fly fishing clinics are popular. Activities vary with the season. Check vallescaldera.gov for up to date information.

We opted for a van tour and were fortunate to find ourselves alone with Carmen, our biologist guide who gave us more than an hour of geologic and historic information, complete with fascinating data about the area’s botany, land ownership, and the movies filmed on the site. Time with Carmen went all too fast; she is a master at making the place come alive—skillfully evoking natural change as well as animal and human activity.

Valles Caldera is home to New Mexico’s second largest elk herd. In the early mornings and evenings visitors can park at one of several elk viewing stations at the edge of the preserve and see herds of the regal animals grazing and occasionally locking their majestic antlers. If you are lucky, you may even be able to hear them bugle. We drove to one of these stations just as the sun was going down, and joined a few other cars filled with people eager for the experience. With binoculars we could see a dozen or more, including several large bulls, along the tree line, but were too far away to hear their calls.

Needless to say, the history of this land precedes by eons its designation as a national preserve. Volcanic activity is believed to have started here one and a quarter million years ago, when a mountain grew for 30,000 years but never blew. This created the Redondo uplift. Some 540,000 years ago lava began to ooze up and form a crack. The uplifts were periodic, the most recent being the Banco Flow some 40,000 years in the past.

Through millennia, there have been some 23 to 25 of these eruptions, each creating the lava domes we see today as vegetation-covered hills. A huge magma field spread beneath the surface of the land. Its collapse created a series of vast lakes. One of the greatest unknowns remains the precise dates of these lake periods. All this volcanic activity was heavy in silica content and produced stands of thick rhyolite rock. Eventually two immense valleys were created, dotted by domes of raised earth. The story of Valles Caldera is all about time and pressure.

Today’s landscape includes great fields of healthy grasses punctuated by evergreen covered hillocks, mysterious rock formations, and evidence of human occupation of the land. Its original inhabitants were the ancestors of the people who now live at Jémez Pueblo, a few miles to the west. Their land use was always communal. As the 19th century gave way to the 20th, ranchers introduced private ownership; four outside families came in 1908. For history buffs, the stories of the Bacas, Oteros, Bonds, and Dunnigans are legion. The cabins remaining from those times are referred to as the Baca Ranch, after one of the families. These people mostly pastured sheep. At mid twentieth century, when the synthetic known as polyester became popular, the demand for wool diminished. That’s when land ownership passed to the public, eventually taking the form of a national preserve.

Carmen pointed to one of the cabins and told us it was used as Longmire’s house in the TV series of the same name. Longmire fans ourselves, we immediately recognized the place. Today this cabin houses the hunting headquarters at Valles Caldera; areas of the preserve are designated for elk and deer hunters and there is pride in their 100% safety record. Lotteries issue licenses to hunt with archery or rifle, depending upon the season.

In addition to several TV series, many movies have been filmed at Valles Caldera. Among them: Lone Ranger (2013), The Missing (2003), Troublemakers (1994), The Gambler (1980), Shoot Out (1971), and Butch and Sundance: The Early Days (1979). A 2013 PBS special, Valles Caldera: the Science, was recommended to us by Carmen as being especially informative.

Aside from its attraction as a tourist destination, Valles Caldera is home to a number of important ongoing studies, some government-funded and some sponsored by universities or other institutions. The reverse tree line, created by too many frequent freezing days for the tree saplings, is of interest, as are the stands of old growth trees. Forest fires are instigated and managed to keep the landscape healthy. A colony of prairie dogs and the Jémez Mountain salamander (an endangered species) are studied.

For those of us who live in Albuquerque or Santa Fe, Jémez is easily accessible, an ideal place to spend a day or plan an overnight. For those who live farther away, it is a worthwhile destination. When we visited, we ran into people from a number of foreign countries, proving once again that those of us who are New Mexico residents often don’t realize what gems we have in our own backyard.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Jemez Country and Valles Caldera”