New Mexico is full of unique byways, some hidden in backcountry, others more routinely traveled. What has come to be known as the High Road to Taos Scenic Byway is one of the latter. Its landscape includes national forest, corrugated badlands, and snow-capped peaks. Villages filled with history are a major attraction. In places, the narrow road hugs winding embankments, in others it crosses open country with huge vistas.

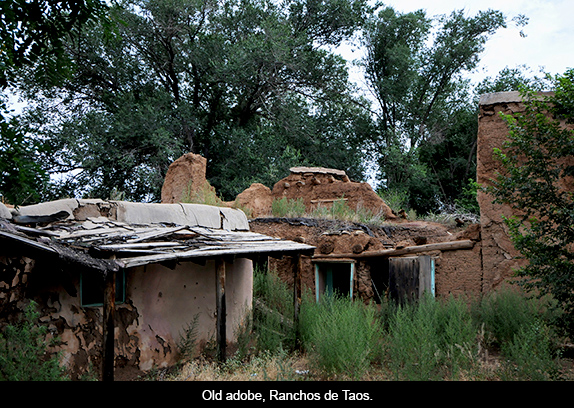

In a series of small communities, one can hear the Spanish of Don Quixote de la Mancha. Remnants of a famous movie set fade beside old churches, examples of architecture that blend the best Spanish colonial with indigenous design and materials.

Luis de Carvajal, the grandson of Portuguese Jews who became “new Christians” out of necessity, was the first governor of Nuevo León, Mexico. In 1590 he was arrested and sentenced by the Mexican Inquisition. That year Carvajal’s lieutenant governor, Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, also Portuguese by birth, led an unauthorized expedition up the Río Pecos to establish a colony in New Mexico. Historians believe that many of the people on this expedition were conversos (Jews who became Christians in order to survive). See Cary Herz’s wonderful book, New Mexico’s Crypto-Jews: Image and Memory (University of New Mexico Press, 2007). Along the High Road, a history of the state’s Crypto Jews hides among generations of Catholic devotion.

The High Road Art Tour takes place each fall, usually in September. Artists and crafts people open their studios and galleries on two consecutive weekends. This is when the aspens blaze a dozen hues of gold, the sky is a rich cobalt blue, and the route comes alive. At other times of the year many of these galleries are open as well, but beyond these places that are geared to tourists one senses a population not overly enthusiastic to make room for outsiders.

Begin your journey just north of Santa Fe on US 285/84. Turn east on State Road 503 toward Nambé Pueblo. The moment you leave the main highway, with its giant casino and other vestiges of a life made to entertain, you are in another world. Nambé, a Tewa-speaking village, was founded in the fourteenth century. The plaza is a registered National Historic Landmark. The prominent church to the right of SR 503 is not original; sketchy efforts to restore the original caused it to collapse. Still, it is a beautiful building with graceful lines and nice woodwork.

Until about 1830, Nambé was known for its polychrome pottery. In the mid to late twentieth century Nambé Ware gained a niche: a stylized and elegant production of silver-colored metal alloy originally created in a foundry in Santa Fe. Of late this local product has been made in China and India, although it is still sold in area shops. Among the more authentic Nambé artisans, pottery is making a comeback—black-on-black and red-on-white—as is weaving. Nambé encompasses 19,000 acres of land, with waterfalls, small lakes, and mountains within its radius.

After Nambé, the landscape opens out to rolling hills and wind-sculpted badlands. In about seven and a half miles you will come to SR 98, or Juan Medina Road, which continues across high desert until it dips down into the green farming valley of Chimayó. Once plagued by an abundance of heroin, Chimayó has managed to clean up its act in recent years; at least the scourge is not so obvious.

The big draw here is the Santuario de Chimayó, built between 1811 and 1816. The inviting church attracts pilgrims from all over the United States and Mexico. They come year round, but on Good Friday the crowd swells to thousands. In the church’s dark recesses, a small hole in the floor of a side chapel is referred to as El Posito. It is filled with healing earth, and visitors leave with a bit of this earth, which they believe has healing powers. Crutches and other relics testifying to miraculous cures adorn the chapel’s walls.

The immediate surroundings of El Santuario de Chimayó have been added to over the years. There are outbuildings where local craftspeople sell handmade santos. Statues and benches abound. A fence where hundreds of worshipers have affixed rudimentary crosses stretches out in back. And shops offering everything from religious candles to hush puppies line the ramp leading down to the church itself.

Rancho de Chimayó is famous for its good food, and a series of smaller eateries also cater to visitors. To get the full feel of Chimayó its worth going there on Good Friday, but there’s also something to be said for a Monday in March, when just a few other tourists do nothing to detract from the peaceful aura surrounding the shrine.

Emerging from Chimayó, you turn onto SR 76, and this is where the High Road really begins. In the distance the Jémez Mountains are blue—and if there’s been enough snow—capped with white. Closer in, especially in the early morning or late afternoon, the crinkled earth of impressive hoodoos cast deep shadows.

Just five miles farther on, take a short detour to the right down into the small village of Córdova. This may be the least changed of the communities along the route. It is known for its traditional woodcarvers, such as George López, whose studio shop is clearly marked and welcomes visitors. López’ santos are unpainted and beautifully carved. He follows the distinctive grain and shape of the wood.

Despite the presence of artists such as López, Córdova gives one the sense it is much as it has been for more than two centuries. Narrow streets overlook the river valley. A couple of elderly men may be sitting on a low wall, sipping beer and conversing. These are farmers who live much as their ancestors did. As close as they are to urban Santa Fe or much-visited Taos, their lives remain apart.

Leaving Córdova, the road continues to climb to the top of a high mesa and enters the village of Truchas. The Truchas Peaks provide a picture-postcard backdrop to this smattering of adobe houses. Truchas deserves a lingering stop. There are galleries, such as the Alvaro Cardona Hine, where Alvaro and his wife Barbara McCauley show their paintings and prints. Alvaro, who is also a fine poet, was born in Costa Rica but came to the US when he was 13. These two artists are New Mexico treasures. A stop at their gallery is delightful.

Truchas, which was established by a royal land grant in 1754, was built as a walled compound around a central plaza. It attempted to create a buffer against nomadic Apache and Comanche bands that often raided the Spanish villages as well as the other Native American pueblos. The inhabitants of Truchas dug miles of acequias (irrigation ditches) by hand, to bring water from the trout-filled river that gave the village its name. Today’s residents still work their farms, although some now commute to jobs in Santa Fe or Los Alamos.

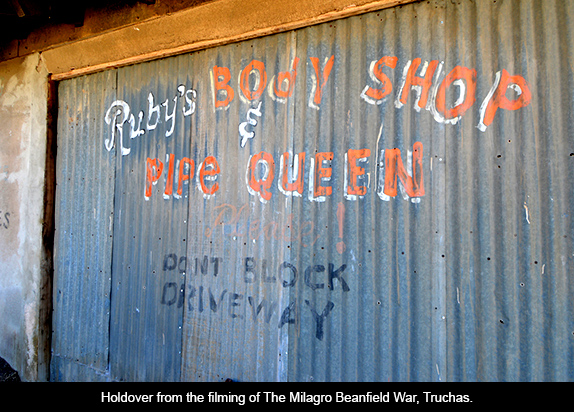

Truchas is also famous for having been the setting for the 1988 filming of The Milagro Beanfield War, based on the book of the same name by New Mexico writer John Nichols. Nichols is another of our state’s living treasures. His many books explore local as well as universal themes. He lives in Taos.

If you haven’t seen The Milagro Beanfield War, it is definitely worth viewing. Robert Redford directed it, Nichols himself and David S. Ward wrote the screenplay, and the roster of stars includes Ruben Blades, Sonia Braga, Melanie Griffith and John Heard. Better yet, read the book. In Truchas, if you dip down to a smaller road behind and to the right of the main thoroughfare, you may glimpse an abandoned building on the side of which you can still see, faded but distinct, a sign advertising “Ruby’s Body Shop & Pipe Queen.” This was one of the film’s iconic locals and the wall is a leftover from when Truchas stood in for Milagro, the mythical village where Nichols’ story takes place.

After Truchas, SR 76 enters Carson National Forest. The trees are larger now: piñón, cedar and spruce. Beetle Kill has been at work here, though, and sadly many of the trees are dying or dead. The once green panorama is mottled with brown. The dead trees, along with several years of extreme drought, add fuel to the yearly fire danger. I have seen beautiful floors made from the gray-blue boards of pine harvested from trees that have suffered from Beetle Kill. But a healthy forest is always the better option.

SR 76 makes a broad swing now, and the next town is Ojo Sarco. It straddles the road, and although I’m sure it harbors its own secrets, we weren’t drawn to explore. Then, almost immediately, there is Las Trampas, best known for its San José de Gracia Church, built in our Independence year of 1776. Las Trampas was founded in 1751 by a royal land grant called Santo Tomás del Río de las Trampas (Saint Thomas, Apostle of the River of Traps). An early smallpox epidemic took its toll, but the place survived. San José de Gracia Church is definitely worth a stop; it’s a National Historic Landmark and houses altar screens painted by well-known artisans. The village is a National Historic District.

After Las Trampas, scenic forest roads lead off to El Valle and Ojito, smaller communities settled by colonists from the larger village. Back on the main road, the next town is Chamisal. Where SR 76 ends, you can either take a short detour to the left and visit Picurís Pueblo, or veer right toward Taos. The village of Peñasco straddles this intersection. In Peñasco a must stop, if it’s open, is Sugar Nymphs Bistro, about halfway through town on the left. This is an unexpected treat: a delicious restaurant where the owners produce wonderful baked goods and even their own ice cream. It also has an art gallery and theater, and has become a center of cultural activity in the area.

Before traveling the last of the route into Taos, there are several more small villages, either on or just off the High Road: Llano San Juan, Llano de la Yegua, and Vadito. Just a few miles east on SR 518, you can find the village and ski resort of Sipapu. Talpa is the last village before entering Taos. It is an ancient site, home to Ancestral Puebloans from 1100 to 1300. Today, as in so many of the other villages along this road, a number of artists live and work there.

As you enter Taos, you may turn right and follow its main street to an always-lively Plaza, with its collection of cafes, restaurants, specialty shops, and such. Moby Dickens is the bookstore whose founder Art Bachrach (recently deceased) knew and wrote about D.H. Lawrence and his group. The store is in new hands and remains an inviting space, although the stock, as in so many independent bookstores, has been depleted by hard times.

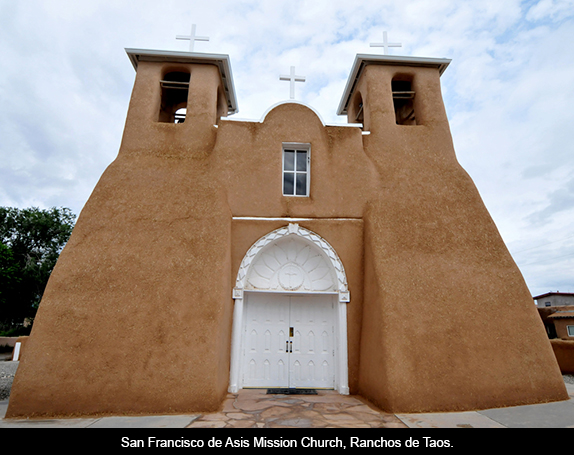

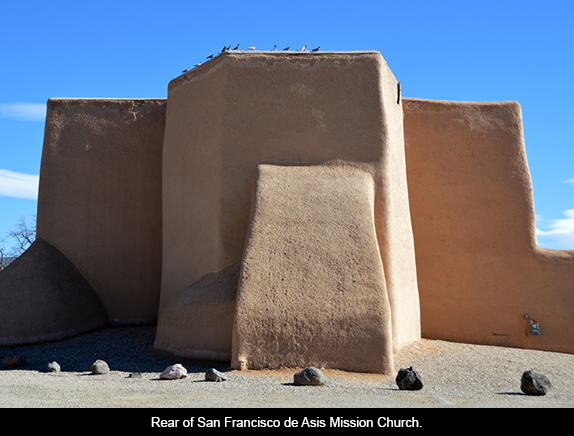

Instead of turning right and continuing into Taos, however, you may decide to go left at the end of SR 518. A mile or so along SR 68 you can visit the famous San Francisco de Asis Mission Church in Ranchos de Taos. You will recognize this beautiful church from the hundreds if not thousands of painters who have painted it and photographers who have photographed it, among them Georgia O’Keeffe, Paul Strand, and Ansel Adams. The church, which is surrounded by interesting shops in lovely old houses, was begun in 1772 and completed in 1815. It has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage site, one of less than 900 in the world. If it’s open you may be able to see the gorgeous interior retablo. And if you’re fortunate enough to visit during the two weeks in June when the church stewards direct their parishioners in an annual enjarre (re-mudding of the church), it will be an even more rewarding experience.

Taos is rich in things to see and do, including the Millicent Rogers Museum, the Mabel Dodge Lujan House, and Taos Pueblo with its multi-storied dwellings and beautiful setting. But perhaps nothing is more interesting than Taos’s inhabitants. Through the years, they are who have given the place its special quality. The town, then no more than a village in the early years of the twentieth century, was home to the extraordinary group of artists and writers that included D. H. and Frieda Lawrence, Mabel Dodge Lujan, Georgia O’Keeffe, Albert Looking Elk, and Agnes Martin. In the 1960s and ‘70s a number of creative artists established communes in the area, including the New Buffalo Settlement and others. A few of these survive.

Jenny Vincent, beloved Taos resident at almost 101, is one of our country’s great singer/songwriters. During her long career, she performed with such figures as Woody Guthrie, Malvina Reynolds, Paul Robeson, and Pete Seeger. And she still sings. Around 11 each Tuesday morning a group of friends visits the assisted living facility where she now lives. One of the regulars is writer John Nichols. They bring their instruments, the staff wheels Jenny to the piano, and she lets loose, much of her energy and fire still on joyous display. At a city council meeting on March 26, 2013, Taos’ mayor declared April 22 (her birthday) Jenny Vincent Day.

Less well known in the mainstream, but also an extraordinary artist and activist, was Rini Templeton (1935-1986). She lived for many years in Taos, and then in a small community just south of the town called Pilar. Heading back to Santa Fe or Albuquerque on the main highway from Taos, you pass the entrance to Pilar as you are awed by the vast sage-dotted landscape stretching west to the dark cut of the Río Grande Gorge. The river shines as it follows the highway. This way back offers a dramatic counterpoint to the High Road’s intimacy.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: High Road to Taos”