A 2006 trip to Egypt, surprisingly, brought me close to a piece of New Mexico I knew little about. We were in Cairo, from where one need only travel to the outskirts of the city to view the famed Pyramids of Giza or mysterious Sphinx. The Museum of Egyptian Antiquities was a place you could spend hours, and still leave knowing there was much left to be seen. Pulsing bazaars, rug and ceramic factories, modern urbanity, ancient neighborhoods with their warrens of fascinating streets, traffic lights that could keep you waiting over an hour: every bit of the metropolis was exciting or frustrating or both. The Arab Spring—with its immense hope followed by violence and despair—was still six years into the future. Tahrir Square was just a busy urban center when we were there.

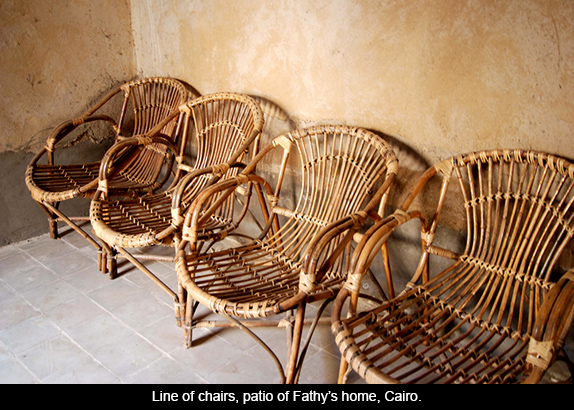

And then we were taken to the home of famed Egyptian architect Hassan Fathy (1900-1989). Fathy’s gracious daughter—or was it his granddaughter?—welcomed us, eager to tell us something about her father or grandfather’s great accomplishments. When she asked where we were from, instead of just answering “the United States” I mentioned New Mexico. Her eyes lit up: “My father built a mosque there,” she said, “near a small community called Abiquiu.” She explained that he’d worked in adobe—a building material we know well—and that the mosque near Abiquiu incorporates an adobe dome without any support but the circle of blocks themselves.

Fathy was a professor, engineer, architect, amateur musician, dramatist, and inventor. It’s hard to say whether he made his mark most emphatically through his ideas, his buildings, or the effect he had on his students. During his long career he designed more than 150 different projects, from modest homes to whole communities—complete with police, fire, and medical services, schools, markets, theaters, and places for worship and recreation. He was famous for utilizing ancient design methods and materials to create contemporary sustainability. He once said: "Any architect who makes a solar furnace of his building and compensates for this by installing a huge cooling machine is approaching the problem inappropriately and we can measure the inappropriateness of his attempted solution by the excess number of kilocalories he uselessly introduces into the building."[1] Words that resonate today more than ever.

Some say Fathy was the greatest architect since Imhotep (BC 2,650-2,600), the Third Dynasty chancellor to King Djoser known for his great learning and love of peace. Imhotep was also a man of many trades and talents: physician, teacher, and perhaps the first architect known to history. Like Imhotep, Fathy devoted his lifetime work to creating habitats that promoted peace and wellbeing.

It was in the 1930s, when he taught at Egypt’s College of Fine Arts, that he designed his first mud brick buildings. He gained critical acclaim for his involvement in the construction of New Gourna, located on Luxor’s West Bank, a community created to resettle the tomb robbers who had been operating in the Valley of the Kings and Valley of the Queens, wreaking such havoc on the country’s priceless cultural treasures. Rather than punish these looters, the government involved them in the creation of their own resettlement.

In 1953 Fathy returned to Cairo, where he headed the Architectural Section of the Faculty of Fine Arts. He built schools and other public buildings. And he traveled extensively, holding a position at the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Boston, among other prestigious posts. He participated in the first United Nationals Habitat conference in Vancouver, in 1976. In 1980 he was awarded the Balzan Prize for Architecture and Urban Planning and the Right Livelihood Award.

Fathy’s book on the project at Gourna was publishing in Egypt in 1969, but gained international attention when it appeared in English in 1973 as Architecture for the Poor. Fathy is a contested figure in his native land. There are those who consider the book’s English title to be condescending, and others who question the uniqueness of the man’s contribution. I find him a fascinating and valuable innovator who, like our own Mary Elizabeth Jane Colter, advanced the practice of looking to the past in order to design for the future. The architect who could have concentrated on building homes for wealthy clients, or made a name for himself by creating important public buildings, preferred to give his talent to those who need it most.

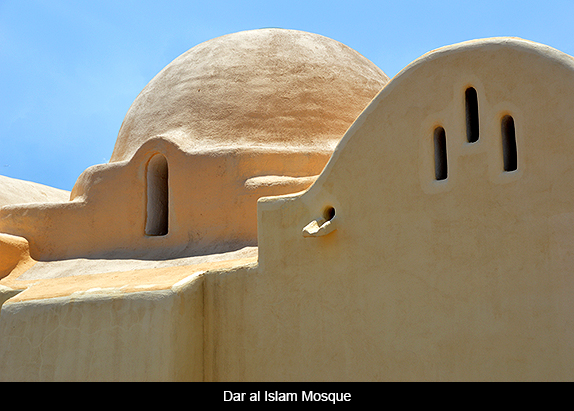

The Dar al Islam mosque, near Abiquiu, New Mexico, is just such a place. Modest in its proportions, simple in its design, and perfectly suited to the majestic landscape it inhabits, it may be the most unusual mosque in the United States. It is a largely hidden treasure less than two hours from Albuquerque, perhaps obscured by its off-road location and by the fact that the Chama Valley contains such an abundance and variety of other destinations.

It’s not hard to get to Dar al Islam. North of Española, on Highway 85, take El Rito Highway 554. Mamacita’s Pizza is at the corner of 84 and 554, and will be your landmark to turn. After crossing the Willie Martinez bridge, immediately turn left onto County Road 155. Continue for approximately three miles. Turn right through a large gate signed for Dar al Islam. Continue along this dirt road until it forks. To the right is La Plaza Blanca, or The White Place, a dramatic canyon of white rock that is also well worth a stop.

A quarter of a mile or so to the left is the mosque. It sits on a secluded juniper-studded mesa framed by nearby hills and with mountains visible in the distance. Below the mesa, lush land borders the banks of the Chama River. When we visited in late September the land was unusually green, due to the year’s robust monsoon season.

The mosque compound includes an educational center dedicated to helping non-Muslims understand Islam and to deepening the practice of Islam among Muslims. The nonprofit organization offers a two-week teacher’s institute to train secondary school teachers in understanding and teaching about the faith. This is certainly a worthy goal at a time when 9/11, and our culture’s ignorant insistence on equating Islam with terrorism, continue to provoke misunderstanding and hate.

The Dar al Islam Mosque, on a rise of land in northern New Mexico, is definitely worth a visit. There are times when those who are not members of the congregation are permitted to enter the sanctuary, and other times when they are not. A permanently staffed office offers information about which parts of the building are open when, and what the protocol is for respectful visitation. But even if you get there and can only view the outside, you are in for an architectural and cultural treat. The Chama valley, one of the most beautiful parts of our state, is fortunate to have such a manmade gem along with its many natural wonders.

[1] Natural Energy and Vernacular Architecture (1986).

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Hassan Fathy in Egypt and New Mexico”