Cuba is an island of eleven million inhabitants, in its 55th year of revolution. Fidel Castro and his 26th of July Movement ousted a dictator in 1959 and proceeded to establish a socialist beachhead in the Americas. The United States, that had long controlled Cuba’s economy and political life, went crazy. Every US administration since has attempted to defeat the tenacious project. Most articles about Cuba focus on the politics of the experience, the contentious relationship between the two countries, or—depending upon where the writer is coming from—either praises the Cuban revolution to the skies or portrays it as a dictatorship that cannot last much longer.

As I say, it has lasted for 55 years: through outright invasion in 1961, the threat of nuclear war in 1962, a US immigration policy that has lured professionals and given preferential status to anyone coming from the island, and scores of lesser attacks, covert actions, destabilization projects, and more. Through thick and thin, resisting a half-century blockade and the implosion of the socialist bloc, Cuba remains a beacon for countries and liberation movements throughout the world that hope to forge an independent destiny. Independent from the US, and now independent as well from what we call “real Socialism.”

This article is not about any of this, except insofar as that history is an inevitable backdrop to the project created by a single man, world-renown Cuban artist José Fuster, in a modest neighborhood on the outskirts of Havana. Fuster lives in the neighborhood called Jaimanitas. He began his work of fantasy following a major hurricane in 1994. Being an island, Cuba is prone to potentially damaging hurricanes. The revolution’s strong organizational skills usually manage to keep people safe. But in 1994 there had been extensive suffering and loss. Fuster wanted to make people smile.

José Fuster was born in the Cuban province of Villa Clara in 1946. His art studies owe a lot to a revolution that prioritized the creation of a National Art School, encourages and cares for its creative spirits, provides them with opportunities to make art throughout the country and to travel internationally to commune with artists from other places. He has studied painting and ceramics, illustrated books, and won numerous distinctions and prizes. With a list of shows and events that fills many pages, today he is best known—by Cubans and visitors alike—for the way he has transformed the neighborhood in which he lives.

Driving out from the center of Havana through the residential area of Miramar, one passes mansions abandoned by Cuba’s prerevolutionary bourgeoisie, embassies, schools, condominiums that house foreign workers in apartments as elegant as those anywhere in the world, the massive convention center, institutes dedicated to scientific research, restaurants and cafés, and rural farmland where Fidel Castro lives. The broad avenue is lined with trees.

One park, in particular, has a dozen or so beautiful laurels, old growth trees whose myriad twisted roots embrace cool canopies in tropical heat. As one drives, one leaves the luxury behind. We are on the outskirts of the city now. The first evidence that we are approaching Jaimanitas is a fanciful bus stop: shelter and bench covered in evocative tile work. Across the avenue there is another.

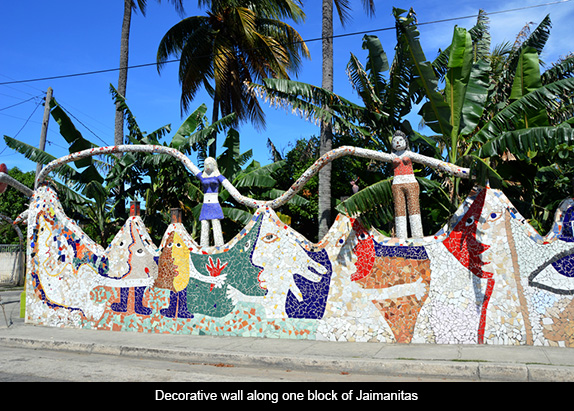

Entering the neighborhood itself, we cannot help but marvel at the panorama. Fuster’s efforts extend, year after year, to involve more and more houses. I first visited Jaimanitas in 2011. It must have been five or six square blocks at the time. This year, when I returned, it had stretched to include many more blocks, many more houses and walls and decorative details.

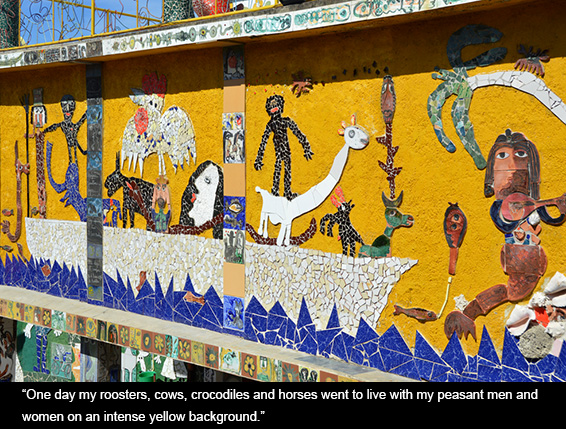

Fuster talks about his project: “The thing is, one day my roosters, cows, crocodiles and horses went to live with my peasant men and women on an intense yellow background. I have no idea how spectators see my work, but for me they vibrate with music. In this one, for instance, singer/songwriter Silvio Rodríguez’ Te doy una canción (I give you a song) echoes eternally. The orchard reminds me of country life and the green mountains of the Sierra Maestra of my youth. And what about the fame of dominoes, our favorite national sport, that lures even those who tend to boast the loudest? My work is a chronicle of these times . . .”

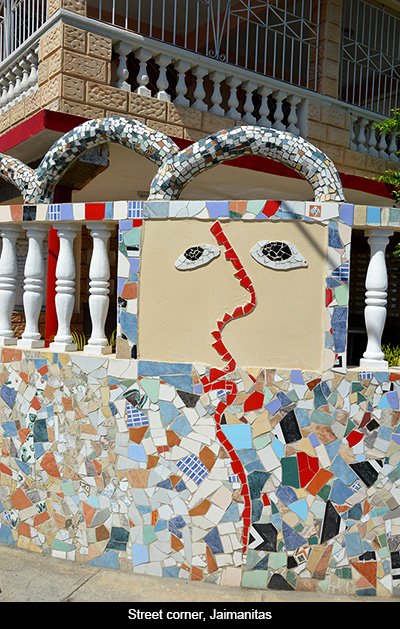

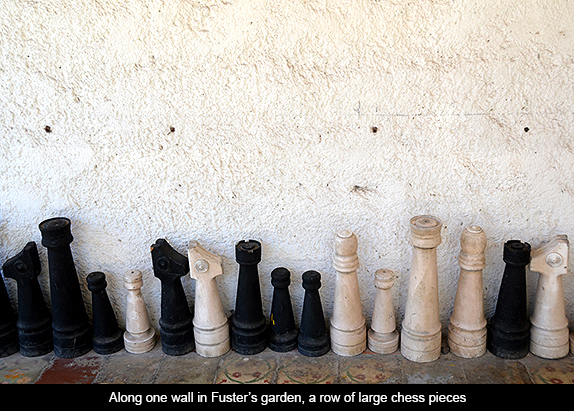

Sections of walls, water tanks, sidewalks, curbstones, benches, and the structures of houses themselves have become palm trees, mermaids, boats, chess sets, love letters, notes of internationalist solidarity, and tributes to such as Gaudi, Miguel Hernández, Fidel Castro and Hugo Chávez. The images are fanciful and evocative. One finds oneself laughing out loud, then strolling farther down the street, turning a corner, and being surprised by yet another magical ambience.

Houses or walls in the process of creation are the most interesting of all. On them, one can see Fuster’s process unfold in an endless territory of delight. These days the master draws his ideas, and a group of five or six apprentices turn them into new works. The centerpiece of the neighborhood, main attraction and magnet for all those who visit, is Fuster’s own home. Fronted by an ornate garden, it rises three stories high, with stairways, areas that hide and reappear, inviting passersby to spend hours exploring this world of the imagination.

Revolution is profound social change. It is hard work, sacrifice, and often involves struggling against enormous odds. It is error and rectification and error again, and again the courage to make things right. But it is also playfulness, a spirit of joy and delight. It knows that without creativity, without art, it will wither and die.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Cuba, Part 3”