Cuban culture, even before the 1959 revolution, was vibrant, original, and multifaceted. The revolution was based on the principal—among many—that culture is a human right, and artistic expression something to be subsidized by the State. Generations of artists, writers, dancers, musicians, filmmakers, and theater people have come of age on the island over the past half-century.

Vigía, a unique publishing venture dedicated to hand-made books that are works of art, started in the city of Matanzas, Cuba, in 1985. No one knows how many titles it has published; at the beginning no one was counting. From its inception, the revolutionary government prioritized the eradication of illiteracy and Cubans devoured national and international literatures with a passion I’ve rarely seen elsewhere. A new title would draw lines outside any bookstore longer than those for bread. Book publication was subsidized, and as a result copies were extremely inexpensive, and large editions sold quickly. Cubans became a highly educated and discerning people.

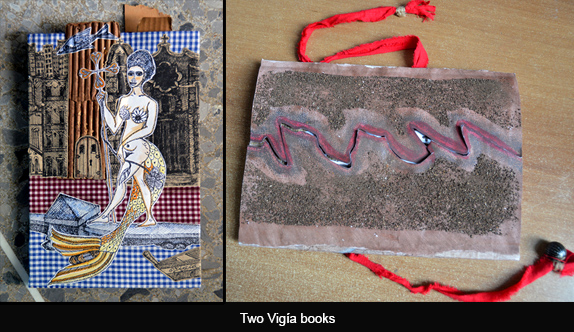

As in all experiences of profound social change, government initiative favored some books while ignoring others. Although there are many different publishing houses in the country, catering to many different tastes, groups of poets and others whose work defied the limits of that which may have been in vogue tried from time to time to launch independent ventures. At first this was difficult, but eventually—as official opinion became more diverse—some of these ventures took off. Vigía has achieved world-class attention. Some US repositories, including the University of New Mexico’s Zimmerman Library, own collector’s copies of a number of its titles. Each book has a limited press run of 200.

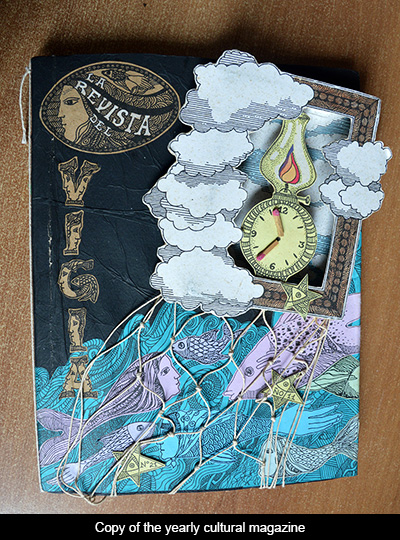

From the beginning, Vigía used rustic materials—waste paper, industrial residue, natural elements, textile components and others—some of them acquired in dumpsters and in the street, to fashion its books. During times of extreme shortages, such as the Special Period of the early-to-mid 1990s, when other Cuban publishers found it difficult to acquire paper, Vigía was able to keep going. A stage set designer named Rolando Estévez conceived of the idea. At first he simply produced invitations to local poetry readings or other cultural events: a poster here, a small pamphlet there. Exuberance and interest were contagious. The enterprise grew quickly, never losing its spontaneity, always preserving its originality and artistry.

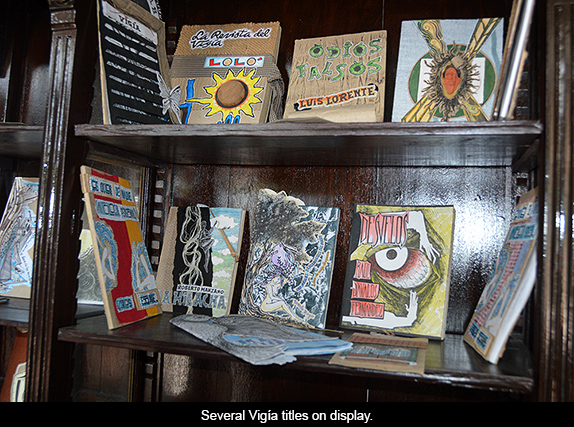

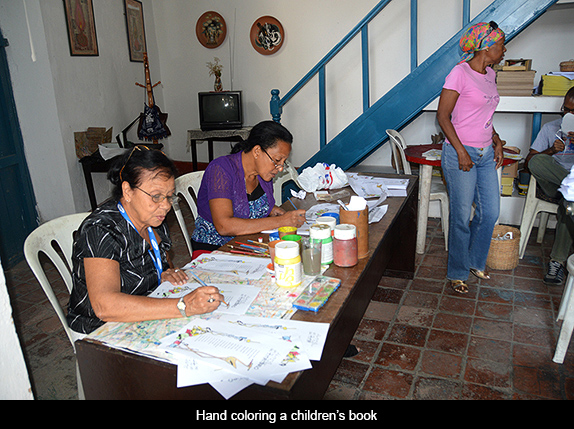

Today Vigía produces La revista del Vigía, a cultural magazine that appears once a year, and a magazine for children called Barquitos del San Juan. Additionally, there are seven collections: Del San Juan (poetry), Trėbol (short story), Barquitos (children’s literature), Venablos (literary essay, history, art and art criticism), Aforos (the classics), Estero (special collections produced outside the confines of the physical plant), Paseo (texts about Havana), and Andante (music). Whenever possible, authors are encouraged to take part in the design and confection of their books. This practice extends to children, who are actively involved in the production of the books for children and the children’s magazine.

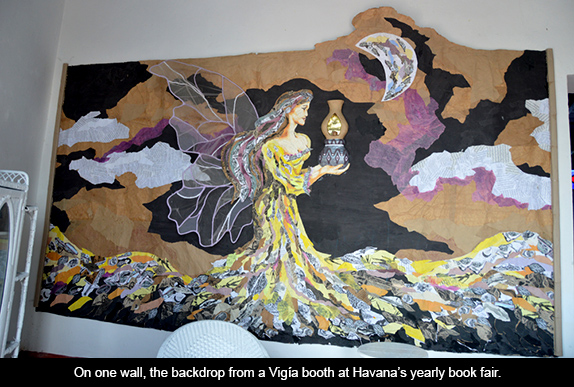

The beautiful old colonial building that houses Vigía is in the historic center of Matanzas City, about an hour and a half east of Havana. Life here is provincial, although the city has a rich cultural history. The house, with its high ceilings, white walls and blue wood trim, is built around an interior patio. Plants abound. At first the publishing venture occupied only the top floor; the ground floor was a gathering place for local musicians. Eventually, Vigía took over the building.

Upon entering the premises, one is immediately hit with the magic of the place. Period furniture—tables, coat stands, shelving—supports exhibitions of some of the titles published over the years. There is an aura of Cuban Baroque, although some books are ornate while others are more austere, depending on content.

In odd corners, people work on different stages of the title being produced at any given moment. Some may be cutting out silhouettes, others are hand coloring, still others are printing, collating or binding. People come to Vigía from many different worlds. Some are newcomers, others have been here for years. One young man, a deaf mute, started as an intern from a nearby school for the hearing-impaired. He had talent, and has long been a part of the project.

Laura Ruiz spent several hours showing me around and giving me the project’s history. An important Cuban poet, she came to Vigía as a typist. Eventually, she worked her way up to editor in chief. Her enthusiasm as she described the place and answered my many questions gave me a sense of a strong collective, in which each member has a role to play but may help out wherever needed.

Today Vigía’s director and chief editor are both women: Agustina Ponce and Laura Ruiz. Gladys Mederos and Estela Ación complete the publication committee. The book designers include Rolando Estévez, who founded the project, Marialva Ríos, Frank D. Valdéx, Abdel de la Campa, Giorge M. Milián, and Mayra Alpízar.

Throughout the international world of books, a world that is disappearing as digital books replace those held in the hand and books that are objects of art become ever more rare, Vigía’s titles are highly valued. The great Cuban poet Fina García Marruz, now deceased, said of the venture: “These editions, born in Carmelite poverty, will one day be sought after. All works of love endure, and this is a work of love.” Eliseo Diego, another Cuban poet now gone, said of Vigía that it was “a lesson about how beauty is never at odds with simplicity and modesty.” And Nancy Morejón, the fine poet who is currently president of Cuba’s Academy of Letters, says about Vigía’s books: “They are the new expression of a sensibility that sweats illusions, good will, fantasy, and a tenacity worthy of a Renaissance metal smith. These editors and poets have achieved a love of the illustrated book, born of an aesthetic that comes from almost nothing: spiritual need rather than anything material.”

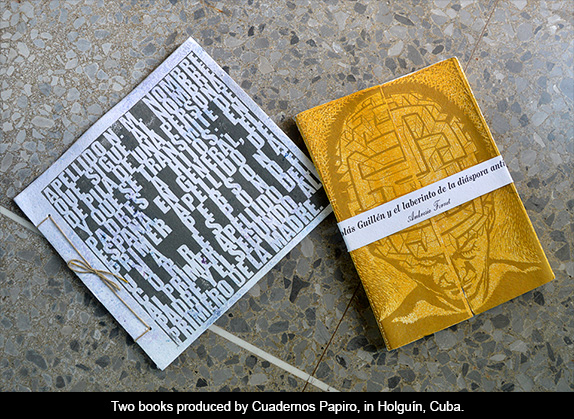

Unique and exciting as Vigía is, it is not the only project of its kind in Cuba. In the country’s eastern city of Holguín, in 1994, the Taller de Papel Hecho a Mano (Workshop of Handmade Paper) began promoting the production of paper in and outside the country. From its inception, it focused on experimentation. Several years later, in 2001, Cuadernos Papiro opened its doors as a publishing house, closely associated with the workshop. Special paper is developed for each book, in line with the text’s requirements.

Cuadernos Papiro is proud of its environmental sustainability, as well as the quality and resistance of its product. Each book advertises the fact that its production did nothing to hurt the natural world. This publisher uses printing machinery from the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries—including a Mergenthaler Linotype from 1900 and a Chandler and Price press from 1816—demanding tremendous effort in terms of restoration and maintenance. The place is more than a printing plant. It is a living museum, reminiscent of an era in which the book itself was a work of art.

Like Vigía, Cuadernos Papiro combines literature, visual arts, and highly developed craft. It, too, limits its editions to a maximum of 200 copies.

When a revolution values creativity and is truly innovative, it promotes such ventures as Vigía and Cuadernos Papiro. Revolution is not only “about bread, but about roses too,” as memorialized in a song sung by the women textile workers during an early 20th century strike in Lowell, Massachusetts. In Cuba creativity goes hand in hand with change. Art is part and parcel of the new society.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Cuba Part 2”