There are countries that suffer such turmoil throughout their history that they seem to disappear and reappear before our eyes, leaving a trail of suffering in their wake. Yugoslavia was often described to me as one of the most beautiful countries on earth, and with a political system to match. Tito was seen by many as an unusually responsive and beloved leader, more in tune with his people’s needs and less rigorously tied to Moscow’s puppet strings. I was never able to visit Yugoslavia, so it’s all hearsay.

By the time my partner Barbara and I decided to board a small ship and sail the Dalmatian Coast, from Athens through the Corinth Canal to Corfu, Albania, Montenegro, and Croatia, then travel inland as far as Zagreb, Yugoslavia no longer existed. What is now Croatia had survived World War II occupation by Germany and Italy, the decimation of three fourths of its Jewish population, its years under Communist rule, and its breakup as a result of the Balkan Wars of the early 1990s that pitted Serbian, Bosnian, and Croatian populations against one another. The scars from that war are barely healed today. In 1995 Croatia won a decisive victory, declaring itself an independent republic. At the time of our trip, in 2010, we reminded ourselves that we were visiting a country that had emerged from high intensity warfare less than 15 years before. Today, as I write, Croatia is a month away from joining the European Union. Fast-track change was evident everywhere, as were ancient landscapes and traditions.

Although we spent less than two days in Albania, and our sightseeing there was limited, it was thrilling to get a glimpse of this most mysterious of all the countries that for so many years remained hidden behind the so-called Iron Curtain. Albania was surely the least accessible of them all. Its leader, Enver Hoxha, led his nation into a sort of paranoia that strains the reasonable mind. I have no doubt that some of his fear of Western encroachment was reality-based. But hundreds of abandoned bomb-shelters dotting the countryside, each large enough to shelter only one or two people, is sad evidence of the extremes to which he went. We learned that Hoxha used all the country’s cement to build these shelters, and imported the material to keep on building them.

Like much of this part of the world, Albania was once dominated by the Romans and Greeks, and you can still see ancient sites from that era. We boarded a bus for Butrint, a marvelous Roman ruin. Along the way we noticed large modern homes, in various stages of construction, uprooted, thrown back down again and left to rot in a startling display of official anger: multi stories at strange angles, poles of rebar sticking up as if pleading for compassion. It wasn’t just a house or two, but long stretches of such structures. When we asked what this was about we were told that people begin to construct an apartment or home and then the government, claiming they don’t have proper building permits, comes along with a backhoe and simply tumbles the project. Personal controversies may be playing themselves out in the public arena. Rage seemed to have supplanted reason. Between the abandoned bomb shelters and uprooted homes, we could tell that we would need months or years to gain some insight into Albania’s present day reality.

All was peaceful and green when we arrived at Butrint. Walking through the well-tended but scantily restored ruins, we could imagine life here during Roman times. At the entrance an elderly woman stood before a small table with a display of silver filigree jewelry. She spoke a few words of English, and proudly told me that this was “genuine Communist-era art.” I could hear nostalgia in her voice.

Our guide, a Croatian woman who clearly appreciated post-Communist freedom, nevertheless told us that if she had to choose between an apartment in a colorful new condominium or one of the ugly blocks of Soviet-era housing, she would not hesitate to choose one in the latter. “The buildings may be gray and featureless,” she said, “but you can be sure the plumbing works and the appliances are of the best quality.”

But Albania was not all Communist and post-Communist contrast. Even in our very brief time we strolled through villages with the solid architecture and artistic sensibility of a people who have endured and will continue to do so. I had the sense that it was still possible to talk to men and women in the street who exude a spontaneity and generosity of spirit as yet untarnished by consumerist madness.

The Dalmatian Coast is like a screen unfolding before your eyes, with one picture-book image giving way to the next. Traveling north, before even reaching Croatia itself, there is the narrow Corinth Canal. Its high walls of sliced rock left inches on either side of our boat; no cruise ship could contemplate transiting. We did so as the afternoon light waned, and shadows lengthened. The experience was wonderful.

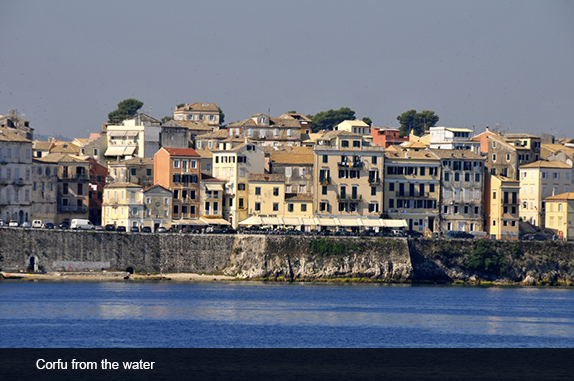

Then there was Corfu, with its rugged stone hills descending almost vertically to slivers of white sand. And Montenegro, like a miniature kingdom of fortified walls and narrow streets. Touristic, yes, but also full of surprises—like the string ensemble that just happened to be playing a free concert when we ambled past the door of a 17th century chapel.

These stops, varying from a few hours to a day or two, were more satisfying than those you make in the Greek Isles or other tourist quick spots, where T-shirt shops and overpriced cafes may be barriers to coming in contact with the ordinary people who call such places home.

As we reached the Croatian coast, our stops were longer and there was more opportunity to explore areas beyond the picture postcard ancient walls and red tiled roofs. Our guide, as I say, was Croatian. During the Balkan War she had been forced to hide in a basement for two years, along with her infant daughter. She gave generously of her own story, helping us gain a sense of what those years of turmoil must have been like.

Once, during an all-day trip inland, I noticed that she would frequently stop to gather leaves, flowers, and the bark of different trees. When we were back aboard ship she asked who might be interested in hearing about the natural medicines the Croatian people use. “We have modern medicine, of course, but many of us still trust homegrown remedies more.” I was fascinated by her two-hour dissertation on the medicinal uses of a great variety of plants.

My intention here is not to write a detailed travelogue on this part of the world, but rather to offer a taste of the excitement this particular trip produced. For whatever reasons, before going I expected a tranquil and pleasant experience, without the dramatic scenery or cultural and political discoveries that have made so many of my trips life-changers. The Dalmatian Coast was surprising in this respect. Woven between those unfolding screens of fortress walls, red roofs, picture-perfect villages and old women sitting in ancient squares embroidering white on white tablecloths, we learned about the tragedy of recent war and a history as replete with conquest and liberation as any on earth.

Dubrovnik is without a doubt a highlight along this coast. As you approach its great walls, what looks like a painting becomes a city. We spent a day and a night exploring the vast network of streets, arches and alleys, and old-time apothecary shops where today’s prescriptions can be filled. We learned that during the intense bombing of World War II people crowded into the walled city to protect themselves from the death reigning down from the air. Bombs did hit many of the old houses, and you can tell which ones because their roof tiles are a lighter red than those that have been there for centuries.

One of my favorite places, along the coast, was the island of Hvar. We walked through Vrboska village, admiring its old houses, canals and graceful bridges. Then we crisscrossed the island, with its endless fields of lavender. Old stonewalls spoke a pattern of land ownership, planting and harvesting no change in political system has been able to alter. We stopped to chat with an elderly woman and her adult son, both gathering the lavender and tying it into small bundles, which we later saw for sale in many public squares. Lavender sachets. Lavender tea. Even lavender liquor.

Trogir is a particularly interesting town, where walking is a joy and turning any corner brings a new view of centuries-old architecture untroubled by the newer construction that meets its inhabitants’ needs. Sundial-type clocks painted on walls. Lazy cafes where an hour or two over a good cup of coffee allows for an email catch-up session as well as fascinating people watching. In Trogir’s steeply slanted main square, a tiny woman who could have been 100 was embroidering a tablecloth that looked as if it could cover a table set for 30. We couldn’t communicate with words, but I sat beside her for a good ten minutes, just watching her talented fingers.

The port city of Split was as far as we went by ship. We docked within walking distance of Diocletian’s Palace, an immense edifice, part ruin part refurbished series of homes and stores, that once belonged to one of history’s most interesting characters. The Roman emperor Diocletian built the massive palace in preparation for his retirement in May 305 AD. It lies in a bay on the south side of a short peninsula running out from the coast. The side you see as you approach from the sea was actually the palace’s back door. In recent years, the city of Split proposed building a shopping mall, underground garage and other additions to the palace, but the people of Split protested and won. We spent several hours exploring the intricate complex, marveling at how people’s homes and apartments are sewn seamlessly into the whole. For a while we stopped to listen to a group of four young men, who regaled us with their magnificent voices. We were so impressed that we purchased one of their CDs, and still listen to it often.

We hated leaving the informal hospitality of the small ship that had been our home for a week. But the next leg of our journey would be overland, to the famous Plitvice Lakes district, where we hiked for one whole day over raised wooden pathways through a wonderland of waterfalls and pools, golden fish swimming just below the surface of the water, and vegetation like I have seen nowhere else. We visited cities and towns of the Croatian interior, and one small village called Gromaca, where 50 old stone houses nestle among farmland and forest.

The inhabitants of Gromaca, we were told, had to flee during the Balkan Wars. They were forced to leave their houses with everything in them. After the fighting ceased, almost all the villagers returned. Our small group split into two even smaller ones to share dinner with two local families. We were hosted by a man and his three daughters; his wife was a member of the village council and had a meeting that night. The youngest daughter, 4-year-old Vican, showed us through an outer room, where the father made wines from local fruits. She was intent on our tasting their sweet grapes. The family also makes and markets its own cheeses, and cultivates varieties of olives, all of which we were urged to taste. Later, the father and older daughters served us a delicious meal of local produce and regional dishes. Their stories of the war were fresh.

We ended our trip in Croatia’s capital city, Zagreb. Rarely have I experienced a lovelier metropolis, with friendlier people or easier public transportation. The old city and the new blend easily. Old churches and public buildings seem to be around every corner. Street markets and fairs proved the perfect venues for interacting with locals while shopping for something indicative of the country. Zagreb is filled with museums and artists’ ateliers, many of them with free admission. When we stopped to ask directions to one museum, someone would invariably tell us about another he or she thought we might enjoy. Art has a living place in these people’s lives, and they seem proud to share it with visitors. And, despite an easy system of buses and trollies, Zagreb is a walking city. Street musicians and frequent pastry shops make exploring a delight.

My favorite museum experience in Zagreb was its Museum of Naïve Art, a small second-floor gallery with a rotating display of naïve paintings from Croatia and elsewhere. The whimsy and humor in some of the canvases seemed a natural fit in this society.

Our feeling when we left Croatia was that, although a couple of weeks are barely enough to scratch the surface of a complex country with a fast-moving history, we’d gotten enough of a taste to want to return.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Croatia”