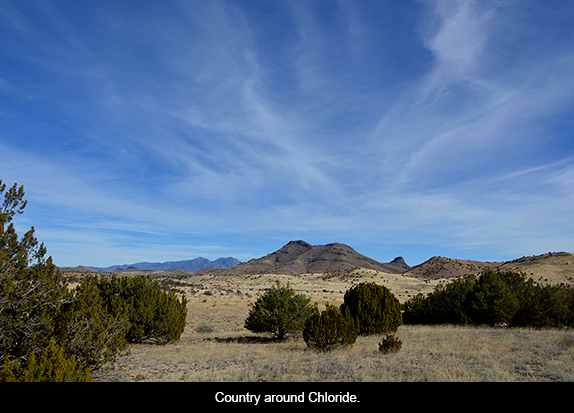

Ever since I heard about a ghost town called Chloride, in southwestern New Mexico, I’ve had a hankering to visit. My partner and I decided to combine the trip with an overnight at our favorite Blackstone Hot Springs Lodge in Truth or Consequences. We drove down from Albuquerque, arriving at the freeway Exit #83 by about 10:30. From there we turned southwest on State #181 and finally onto Forest Road #52. State roads and even the Forest Road are paved all the way. The land is unexpectedly beautiful. I kept thinking we would see antelope or deer, but they must have been hidden in the hills. Occasional cattle grazed here and there.

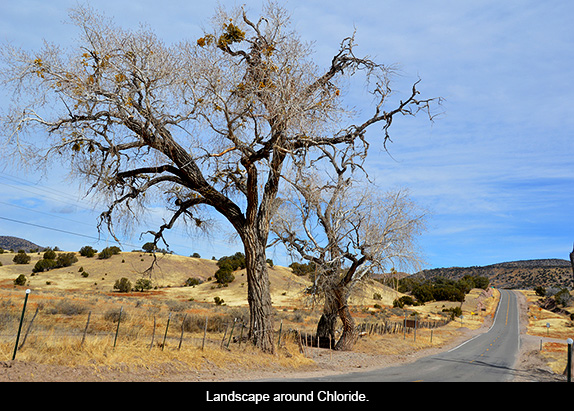

Soon after leaving I-25 we found ourselves in a valley like a vast broad-based bowl, with gentle hills rising all around. Farther away we could see a circle of higher peaks, one of them quite imposing. To our left was the Black Range over by Silver City. Juniper-and piñón-dotted humps made for an ever-interesting landscape, through which a very well kept-up road twisted and turned, fell and then rose up again. This was once Apache country, and then a silver mining area, but today it is home to vast ranchlands. Along the road we would see the occasional entranceway to a cattle ranch or a country mailbox with an oversized spur adorning it. The soil was a rich red, then a dozen shades of cream, then brown or red again. Despite the dearth of recent rains, the ground cover still showed some grasses and small shrubs, mesquite and Cholla cactus with thirsty withered arms. The far mountain peaks had a light dusting of snow, much less I imagine, than in years past.

Four tiny communities remain in this area from the great silver mining boom of the late nineteenth century. The first one we drove through was Cuchillo, a small scattering of old houses, some abandoned, others still inhabited. Modern-day trailers seem to be the most recent additions. A few miles farther on we came to Winston, the largest of the three. A welcoming general store has regular and diesel gas tanks out in front; I imagine they service ranchers for miles around. We stopped to have a look around and talk to the friendly woman behind the counter. An assortment of handguns, rifles, buck knives, binoculars, and cheap turquoise jewelry occupied the glass-fronted showcase. Restrooms and a small selection of fast food were available.

Chloride is only two and a half miles farther down the road, but it is a world away. Mule trains hauled freight through here in the 1870s, and it was a U.S. Army muleskinner named Harry Pye, bringing in goods for the U.S. Army, who first noticed a “float” in an area stream. He thought it might be chloride of silver ore. When he retired from the Army he had it assessed, and immediately staked a claim, but was murdered a few months later (the literature says by Apaches, but of course the miners were the ones who invaded the Indians’ land, so that sort of “history” probably has an untold backstory). At one time there were as many as 3,000 miners living in shacks, digging ore and hoping to get rich. Chloride boomed until the end of the 1890s, when the US adopted the gold standard, silver quickly lost its value, and the population of the town went from 3,000 to 100 in a matter of days.

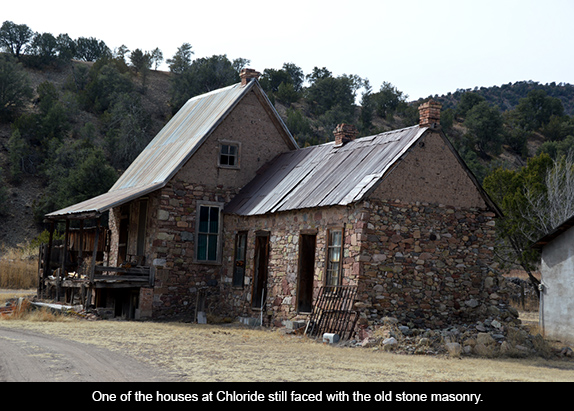

As soon as we arrived we knew this place is unique. A few very old houses line the main (and only) street. Actually, 30 structures remain from the time of Chloride’s greatest population density. Some are in ruins, others look to be in some state of reclamation, and a few have been completely restored, using as much of the original building material (beautiful old stone masonry, cast glass windows, and great beams of Ponderosa Pine) as possible. Alongside these 130-year-old structures the population of 13 have built a few modern homes, but they blend into the landscape and don’t detract too much from the older buildings. A couple of old mining shacks have been renovated as vacation rentals, and there are two pit toilets for the benefit of visitors. The tiny community is very tidy and clean.

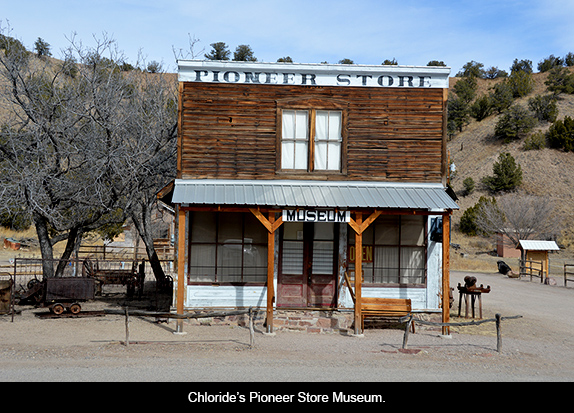

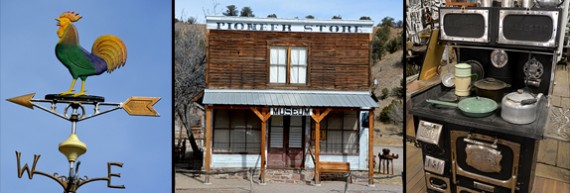

Over the past couple of decades, three buildings have been lovingly and accurately restored from their days of glory and long period of abandon. One is the Pioneer Store, now a museum and the place that drew us to Chloride. Don and Donna Edmund and their daughter Linda, one quarter of the town’s current inhabitants, have dedicated their retirement to researching this extremely interesting store, bringing back its structural integrity, and opening it to the public from 10 to 4 every day. Next door they have reconditioned another building, one of the original town’s nine saloons—now a cooperative gallery for the area’s artists and craftspeople. We saw quilts, ceramics, jewelry, hand-made books and more, all attesting to the creative bent of many of the people who choose this isolated life.

Across the street is the other newly renovated building. Originally intended as the community’s bank, it never opened as such. While banks today may be “too big to fail,” this one turned out to be too small to succeed. Before it could open its doors the man who hoped to run it realized he didn’t have enough cash on hand. The general store, nine bars, at least two brothels, a butcher shop, millinery, assay and law offices, candy shop, and other enterprises could barter their way to some sort of short-term stability. The bank would have had to have access to cash that didn’t exist, and so the man who wanted to open the bank gave up and it became the town’s ninth bar. Men so outnumbered women in Chloride that the “city fathers” are said to have offered a free tract of land to any woman who wanted to live there.

Eventually this structure fell into total ruin, with only a couple of half-walls still standing. The people who bought it were able to use the rubble of gorgeous local stone to rebuild, and retrieved some of the old beams as well. Itinerate Mexican workmen proved to be excellent masons and also made adobe in situ; and the place recently reopened with a real feel for what it must have been like at the end of the 19th century. Since this past August, it enjoys its reincarnation as a café and the local people finally have an eatery. The café is run by Tom and Lori Merrihew. When I complimented them on their bread, Lori pointed to Tom and said: “He’s been baking for 38 years.” We were fortunate to have come when we did, because it’s only open for lunch from Wednesday through the weekend. The bread and food in general was fresh, simple and delicious. Someone mentioned that the cinnamon rolls are the best for miles around.

The absolute gem, though, is the old Pioneer Store. It was locked when we arrived, with a note on the window instructing visitors to go to the other end of town and knock on the Edmund’s door. We did, and Mr. Edmund told us he’d contact his daughter Linda. As we left I could hear him calling her on his walkie-talkie. By the time we got back to the museum, she was walking up with a key in her hand. When she opened the door and ushered us inside, I could hardly believe my eyes.

This store opened its doors in 1880 once the silver rush was underway. It closed them in 1923, when the family that owned it had no one left to take care of day-to-day operations. By that time the silver boom was long over and the town’s 3,000 hard-working hard drinking miners had gone. The population was reduced to around 100, and then 13 (and the population has remained stable since). The owner of the Pioneer Store closed the door, boarded up the windows and secured the boards with tin, and left every bit of merchandise inside. The place remained empty for the next seventy years!

Amazingly, during those seven decades only bats and rodents made their ways inside. It may have been the isolation of the area that kept humans out. Mining equipment, pots, pans, scales, tools, canned and bottled goods (complete with contents), old irons, dental equipment, saddles, bridals and everything else necessary to frontier life remained mostly intact.

At the store-museum, Linda’s was the voice of experience; and as she spoke I could tell she was accustomed to sharing as much or as little of the fascinating history as she thought her listeners wanted to hear (we were rapt, while another couple who visited while we were there barely spent five minutes inside).

“The Pioneer Store was built by Mr. James Dalglish in 1880,” she began. “He had come to the southwest from eastern Canada to improve his failing health, and he built the large, log building of hand-hewn Ponderosa Pine logs harvested from the mountain forests to the west of present day Chloride.” We told her we’d noticed the enormous size of the posts and beams, many of those with the greatest circumference quite high in the building’s structure. “Yes,” she said, “it looks like they used those beams in the order they brought them down from the surrounding mountains.”

And she continued, “By late 1880, the building was completed and The Pioneer Store opened for business. Mr. Dalglish operated it throughout the silver boom years of 1880 through 1897, stocking all the goods needed for the miners and their families. The store sold all manner of household goods, including food for residents and their animals, clothes for the entire family, mining equipment and tools, and ranch equipment and supplies. Wagons, buggies, and other large items could be ordered, as well as such specialty items as brides' trousseaus. A United States Post Office was established in the front part of the store in 1881, and a newspaper, The Black Range, began publishing weekly from the upstairs rooms the following year. The large safe in the store building served as a local Bank for the remote mining operators and for the scattered ranches. It also served as a ‘Pawn Shop’, as records show: ‘$2.00 loaned on watch’ was on a piece of paper in the safe.

“When the Silver Boom ended in 1896, Mr. Dalglish leased the store to others who continued its operation until 1908. At that time, the building and its contents were purchased by the U.S. Treasury Mining Company. That company soon became the property of the James Family, who had arrived in Chloride in 1882. The Jameses had six children, three boys and three girls. Mr. James died when the oldest was 14, but those kids got together, in line with the spirit required on the frontier, learned a number of businesses and did very well. Eventually they owned mining, lumber and cattle interests, as far east as what is now Truth or Consequences and west to the Gila.

“The Jameses operated the store as a commissary for the employees of their mining, timber, and ranch operations, but by 1923, most of the residents of Chloride had moved on, and their businesses had fallen on hard times. The family decided to close the store, and sealed it up with everything inside. The idea was that by the time the youngest son, Edward Jr., got an education, the town of Chloride might experience a resurgence, and he would have a business to step into. It didn’t work out that way. Edward Jr. was educated as a Scientist. His work back east, then at Los Alamos (on the Manhattan Project), and finally at Livermore Labs in California, kept him from returning to Chloride except for an occasional visit.

“When my father met Mr. James on one of his visits to Chloride in 1979,” Linda said, “they found they shared a strong interest in preserving what was left of a once bustling, but now almost deserted, silver mining boomtown. Mr. James showed my parents the old pioneer Store building, and in spite of the fact that it had been closed for 68 years, and was full of bat and rodent debris, it was an obvious treasure trove of the past. They all agreed it should be a museum, but he lived in California, and my parents lived in Las Cruces, and only had weekends to spend in Chloride, so there was no one to do the restoration work. My father retired in 1986 and moved to Chloride to live. That was when they and Mr. James again discussed the museum project. In 1989, he agreed to sell our family both the Pioneer Store and the adjacent Monte Cristo Saloon, including the contents of both buildings.

“We immediately began working on an application to have both buildings placed on the New Mexico State Register of Cultural Properties. Both the Pioneer Store and the Monte Cristo Saloon buildings were accepted to that list on March 22, 1991, as numbers SR1538 and SR1539 respectively. The restoration and refurbishment of the Pioneer Store building began in 1994, and was completed four years later. The exterior had to be straightened from years of sagging; the ponderosa pine logs had to be re-chinked; most of the window frames had to be rebuilt and re-glazed; and both the roof and the foundation had to be redone.

Linda opened the safe to show us its pristine interior. It is a Mosler by Bachmann & Company, made at the Charriot Safe Company in Denver, Colorado. On the dulled outer door, in faint letters, one can still see Patent January 2, 1883. The hulking furnishing is a beautiful piece of art and engineering, with intricate painting on the black matte field of its thick doors. While the bats and rodents defaced parts of the outer doors, the safe’s inner sanctum has been preserved intact. I was riveted as she described that amazing moment when Mr. James, who still possessed both the outer combination and inner keys, opened that safe that had been closed for so many years. It contained property deeds and much else. Except for what he needed to hold onto, because it pertained to properties he still owned, he donated everything to the present day museum.

“In the store’s interior, we found that most of the town records from 1880 to 1923 had been stored in boxes that had been stacked high. Over the years, the boxes weakened and toppled over, spilling the contents over nearly the entire length of the building. Before the interior work could begin, all of these records had to be picked up, cleaned, and repacked until they could be sorted and classified. The building contained approximately 50 boxes of personal, business, and town site records.

“Because of the extensive bat and rodent debris, all of the store furnishings and items that had once been the store’s inventory had to be taken out, cleaned and refurbished. Once the interior was cleaned and re-white washed, the furnishings were reinstalled as they had been, and the store’s inventory was replaced on the shelves. About eighty percent of what you see here was found here,” Linda said. “The other twenty percent came from other parts of the community and were probably purchased at the store. The only piece of furniture that was never moved was the safe; it weighs 6,000 pounds!”

What I found most fascinating was the safe, and a large black steel device called a Credit System, probably four feet high by two feet wide, standing atop an ancient cash register made by the McCaskey Register Company in Alliance, Ohio. Linda said the cash register came later, and was made to fit the box. This was the store’s “data base,” where large horizontal loose-leaf shelves held everyone’s accounts, debts, and so forth. There was a lock between the upper and lower sets of shelves, such that the storeowner could run out for a beer and his employee continue to attend to customers while not having access to the store’s bookkeeping. This device worked on electricity: two dry-cell batteries linked together to produce three volts. A 5-button combination keypad is located just above the cash drawer. If you operated the keypad correctly, a bell would ring, the cash drawer would fly open, and the paper tape device would ratchet a receipt out about two inches so the clerk could note the sale information. At that point in time, they did not yet have print units or adders, so that data had to be entered by hand. When Don Edmund entered the building for the first time, the device still worked, and if hooked up to electricity does so to this day.

After our visit I was able to ask Edmund a bit more about this fascinating device. He told me that he and his wife have traveled extensively and enjoy visiting out of the way museums. They have yet to see a machine like the one at The Pioneer Store. When he asked the historian who showed him how theirs works why they have never seen another, the historian said there are very few of them in existence. He conjectured that any mercantile still in business would have replaced such a bulky item as soon as a smaller unit with more capability became available. The fact that The Pioneer Store remained closed for so long was probably the reason this device was still there.

Visiting Chloride was like visiting the past, and also like visiting a place with a sort of community pride not often encountered these days. It was strangely moving to see the beautiful old tools, instruments of everyday life, canned goods with their original labels, clothing from so many years ago, and other items from a time when good craftsmanship was so much more in evidence than it is now. The system for carrying debt and recording accounts payable and such was particularly fascinating to me. Its great black metal container also acted as a fireproof safe; buildings in those days were extremely fire prone and if they were to go up in flames their records would not have survived. This, then, was another safe in the event of fire. In one of the museum’s glass exhibition cases the store’s first ledger, dated May 1881, is displayed.

Linda told us that the store has officially been a museum since 1991. It has been written up in some of the state’s travel publications, and visitors show up at the rate of several a day. Clearly, this is only the beginning for a community with this sort of pride in its history and such devotion to preserving and recreating its past. Chloride is on the New Mexico map of ghost towns. But I wonder if a place with 13 active residents can be called a ghost town.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Chloride”