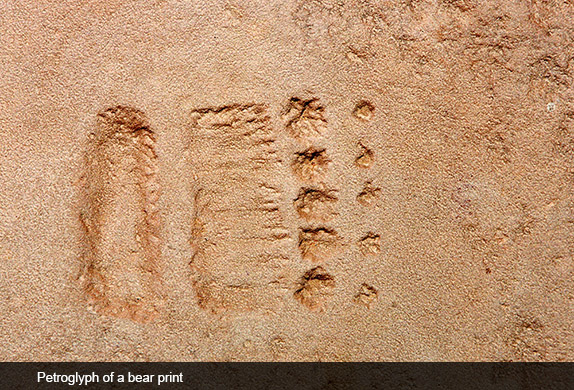

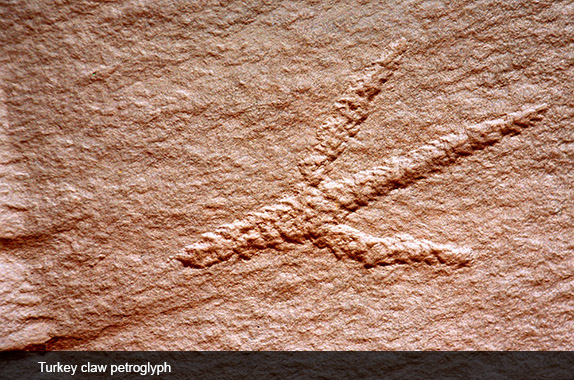

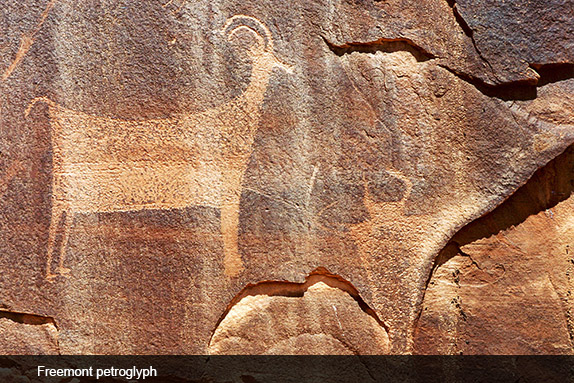

Footprints. Ours and those from a thousand years ago. A fresh bear print visible in the soft mud banking the clear waters of the river that cuts through these Narrows. A much older petroglyph bear print. A petroglyph showing a pair of child’s feet, each mysteriously endowed with six toes (some indigenous cultures attribute special powers to children born with six toes). A single large petroglyph of a turkey print. Hiking the vast canyons of the Escalante today must be something like hiking Grand Canyon two centuries ago; running into another human being is unlikely and the sound of our own feet against slickrock vies for our attention with the sound of our beating hearts.

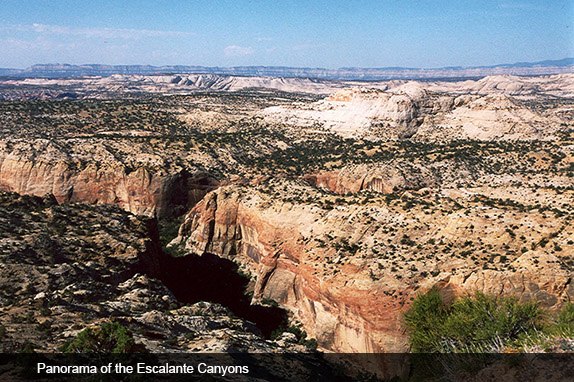

We have come to this vast jigsaw in southern Utah called the Canyons of the Escalante. As far as the eye can see, rugged multicolored sandstone undulates, rises and dips through the Escalante River Basin—a panorama of vertical canyon walls, water pockets, narrow slot canyons, domes, pedestals, arches and natural bridges. For 1500 square miles the land rises from 3,600 feet to over 11,000.

Dinosaur fossils more than 75 million years old have been found in the area. Humans didn’t settle permanently here until the Basketmaker III Era, somewhere around 500 AD. Ancestral Puebloans gave way to the Fremont people, and both grew corn, beans, and squash in its valleys and canyons. Rock art and ruins abound. The first record of white settlers dates from 1866, when Captain James Andrus led a group of cavalry to the headwaters of the Escalante River. In 1879 the San Juan Expedition crossed through what is now the Monument on its way to establishing a Mormon colony in the far southeastern corner of Utah. In otherwise vertical cliffs, the only pass they found was at a place they called Hole In the Rock. It took them six weeks to make their way through the narrow, rocky and extremely steep crevice, finally having to rig a pulley system to lower their wagons and animals off the cliff. Then they built a ferry and crossed the Colorado, climbing back out through Cottonwood Canyon on the other side.

Today the name Hole in the Rock Road denotes a narrow byway with shear drops on both sides. Although paved and in many cases an example of expert modern engineering, the main road running from Boulder to the small town of Escalante (driving west toward Bryce) is also treacherous, especially at night.

The tiny village of Boulder (Boulder, Utah, not the much larger Colorado town of the same name) is the jumping off spot for any exploration of the Escalante. Its most recent number of inhabitants is listed as 100. Here a couple of modest motels and one gorgeous retreat, The Boulder Mountain Lodge, host those who are about to do the jumping off—and a more fitting description is hard to come by. Here, too, is Escalante Canyon Outfitters (ECO), a company offering well-conceived weeklong camping experiences into several arms of this wilderness. Grant Johnson, with decades of area knowledge in his backpack, organizes and leads the small groups. His wife, Sue Fearon, manages the company. There is no better marriage, anywhere, of love for these canyons, wisdom, experience and expertise.

We gathered, along with five or six others, at a local café. As requested, we had arrived with no more than 20 pounds each of clothing and other necessities. Our variety of bags would be transferred to the regulation duffels to be carried by Grant’s horses. We were each responsible for a small daypack. Following an hour or so drive over dirt roads to the trail head, we began our five-mile hike over slickrock, along ledges, and through other features of this magical landscape to the riverside spot where another ECO guide had already unpacked the horses and begun setting up the camp that would be our home for the next few days. Along the way we saw views that stopped us in our tracks, a variety of cacti in bloom, and clusters of “desert marbles” on the ground. These differently sized balls with two perfect hemispheres look like miniature cannonballs. They are mineral deposits that form around a grain of sand.

Johnson himself had to carve many of the canyon’s access trails, paying attention to what his horses were able to navigate safely. Years of personal exploration have produced the perfect backcountry host. ECO keeps its offerings rich and prices moderate. Each group is accompanied by two guides, making it possible for those who desire the most ambitious hiking and those who want to hike more modestly to come away with equally memorable experiences.

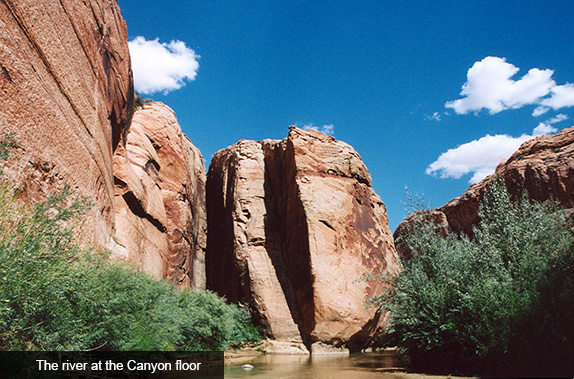

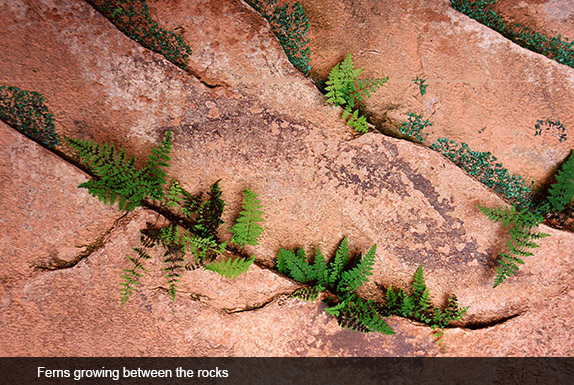

During our five days in The Narrows, we waded the river to splendid sites of Fremont rock art, collections of corncobs picked dry 800 years before, those elusive footprints in mud and stone, and secret fern-laced alcoves—one of them aptly called The Cathedral. We made our way through passages barely wide enough for a single body and climbed to higher elevations where pockets in the rock, called tinajas, were filled with water that reflected a sky of lazy clouds floating in brilliant blue. Some of these pools were deeper than we were tall. In the evenings we gathered back at camp, enjoyed delicious meals prepared by our guides, and bathed in the cool waters of the river. At night we could hear the sounds of creatures lost in the hubbub of civilization.

An overriding sensation was one of isolation, true wilderness. As I say, during our entire week in the Escalante, and another week at the end of that same summer when we decided we just had to take another of ECO’s trips, we never came upon another human being.

The headwaters of the Escalante River spring from the slopes of the Aquarius Plateau. As it flows into this landscape it has carved, it branches out into lesser rivers and creeks until it meets up with the Colorado River, southeast of Coyote Gulch and now beneath the surface of Lake Powell. The Kaiparowitz Plateau also sends waterways down into these canyons. And tributaries flow in from the north and east: Death Hollow, Calf Creeks, Boulder and Deer, The Gulch, Wolverine, Silver Falls Creek, Choprock, Moody, Stevens, and Cow Canyons. Some originate from as far away as the Waterpocket Fold in Capitol Reef National Park.

The Grand Staircase-Escalante, at 1.7 million acres, was declared a National Monument by Bill Clinton in September of 1996. It was the height of Clinton’s presidential election campaign, and it is clear that he hoped to show his passion for wilderness protection. The designation was controversial from the moment it was announced. Local officials and congressmen objected to the Monument, questioning whether the Antiquities Act allowed such vast amounts of land to be set aside in this way. Clinton upped his stock with environmentalists, while creating problems for Utah’s state school system, highway infrastructure, and others. That November he won Arizona by 2.2% and lost Utah to Republican Bob Dole by 21.1%.

People like Grant Johnson, who inhabit and love the Escalante, had their own objections to making this land a National Monument. They feared development would encourage an influx of tourists that would forever defile the place. So far, this has not happened, but it is likely inevitable. This National Monument is the first in the nation to be managed by the Bureau of Land Management rather than the National Park Service. Visitor Centers are located in such far-flung places as Cannonville, Big Water, Escalante and Kanab.

The canyon lands of the Escalante are immense and rugged. The sandstone layers we see today were deposited during the Mesozoic era, 180 to 225 million years ago. At the time, the whole area was covered by sand dunes. About 80 million years ago, near the end of the Cretaceous period, the entire western section of the North American continent entered a period of uplift and mountain building. More recently, additional uplift formed the Colorado Plateau. These episodes raised the Aquarius Plateau, and eventually strong erosional forces acted on the whole Escalante River Basin. Wetter climates during the ice ages contributed to the deep cutting of canyon walls.

From whatever direction you approach the Escalante, getting there is much of the thrill. If you come in from the south you will travel the Burr Trail Road, arguably one of the most beautiful routes in the country. Only 30 miles of the Burr, also called Route #12, are paved, so you’ll want to be driving a car with high clearance. Here you are in the backcountry of Capitol Reef (another National Park with a low number of visitors and well worth a few days). If you approach from the north you must come over 11,600-foot Boulder Mountain. Terrain and vegetation change with altitude. Vistas are endless and breathtaking.

The village of Boulder, aside from the aforementioned lodgings and eateries, and in addition to the fact that it is home to Escalante Canyon Outfitters, houses the small but interesting Anazasi State Park Museum, located on the site of a village dating back to between 1050 and 1200 AD. The museum has both a six-room life sized replica of the Ancestral Puebloan ruin and the remains of the 87 original rooms excavated by University of Utah archaeologists.

If the footprints of every human and animal who ever wandered the Escalante wilderness were visible in some sort of time warp pattern from ancient times to ours, clear trails would crisscross vast untouched areas. We might be able to trace the paws of animals long extinct, barefooted natives searching for food, and the Nike- or sandal-shod hikers who venture into the Canyons today. There is something very special about roaming a place so few others have explored.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Canyons of the Escalante”