Canyon del Muerto, Massacre Cave, Mummy Cave: names that denote the death and destruction that besieged the Navajos of Canyon de Chelly from their earliest claim to this beautiful place. Indeed, the history of Canyon de Chelly is one of attack and resistance, terror and survival. Even the name itself has suffered desecration. Spaniards couldn’t pronounce the Navajo Tséyi’. Chelly (pronounced shay) is the closest they could come. Tséyi’ means canyon, or inside the rock.

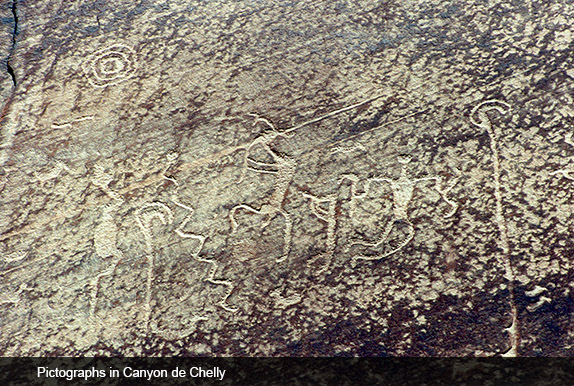

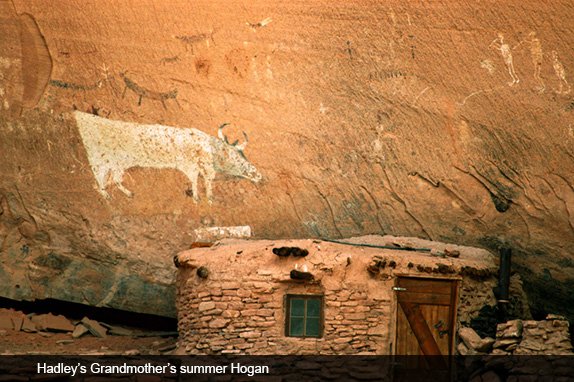

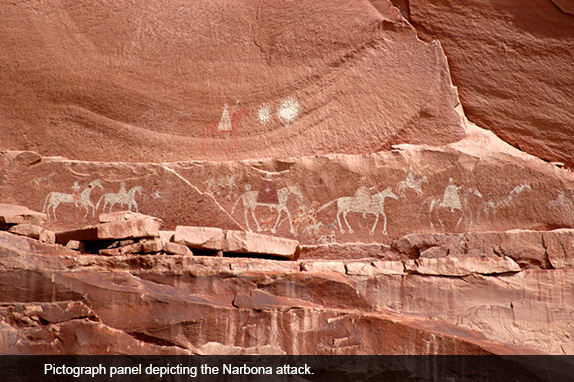

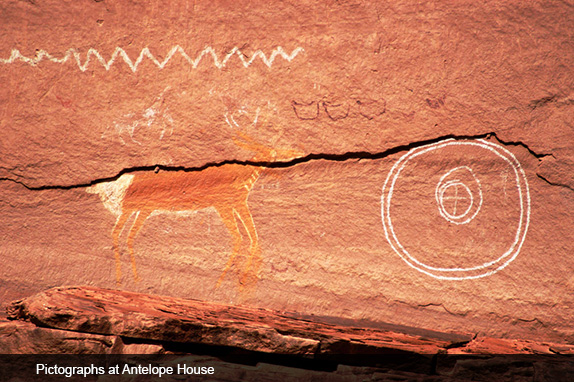

But Canyon de Chelly is also a place of beauty and peace. Although terrible atrocities were perpetrated here, and they are vividly recorded in pictograph and legend, the history ends up being one of survival. Dozens of Navajo families descend into the canyons to spend the summer, emerging to the rim communities again when winter returns. Year-round natives work as thoughtful guides, taking visitors to experience the natural and historic wonders that reside between the canyons’ magnificent walls.

Canyon de Chelly contains evidence of life dating back to the Basket Makers, and Pueblo I and Pueblo II periods. Four thousand years of human habitation can be traced. Navajo or Diné people entered the canyon in the mid-17th century. The National Monument was established in 1931, as a unit of the National Park Service, primarily to protect the large number of ruins and other examples of Ancestral Puebloan life. But the Monument is located entirely within the large Navajo Nation. It is the only park in the system entirely owned by the Navajo Tribal Trust and cooperatively managed by the tribe. From Albuquerque, drive west on I-40 a few miles past the Arizona state line, then turn north on #191. Chinle is the small Navajo town just west of the canyon. You are there in five and a half hours.

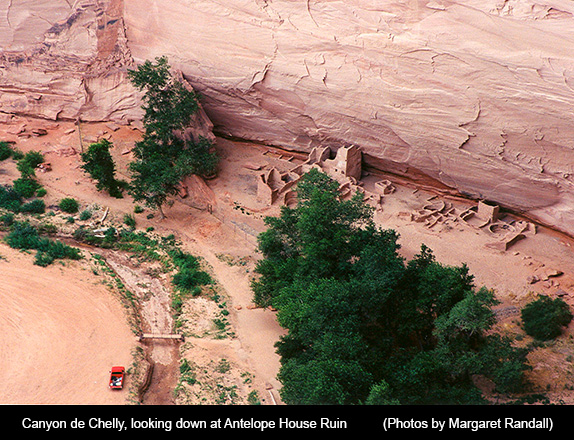

There is no fee to enter the Monument or drive along the Canyon’s north or south drives, from which—at the end of short access roads—you can look down onto multi-hued rock formations and several of the ruins visible from a distance. There is no fee to make the only hike permitted to those exploring without a guide: the lovely 2-mile-roundtrip trip down to White House ruin and back. But Canyon de Chelly can only be fully appreciated by spending a couple of days and entering other reaches of this spectacular red-walled canyon system, composed of Canyon del Muerto, Canyon de Chelly, and Monument Canyon.

For this it is necessary to stop at the Visitors Center and hire a local guide. At $15 per hour, regardless of the number of people in your group, it is more than a bargain. Or, at the same Visitors Center or one of the three motels in Chinle, you can book a half-day or day trip in a World War II heavy duty six-wheel-drive vehicle—an open bus on a truck chassis—, take one of several private jeep tours, or sign up for hourly exploration on horseback.

I have been to Canyon de Chelly many times. I have gone into the Canyons in one of those odd buggies, by horseback, and hiking. I have asked for a number of hours visiting ruins or hikes where rock art was prominent. Once, with some friends, we hired a guide to take us to some part of the canyon complex where silence would be our companion. We were interested in seeing ruins and rock art, we said, but our main objective was to get as far as possible from the life we all led beyond these canyons.

Our guide that day turned out to be Hadley, a man in his mid-thirties. He was an artist. Like many of the Navajo people who work as guides, his family had lived in and around Canyon de Chelly for generations. He accompanied us in our car to a spot near the rim. Hidden among the trees, a trail dropped into the canyon. Three of us would hike, and a forth would pick us up at a prearranged trailhead some five or six miles distant. Our guide told her: “Meet us at the white trailer around 5 this afternoon.” Unfortunately, there were many white trailers in those woods. And instead of 5 p.m. we emerged some three hours later. It was dark by then. Unfamiliar with this different attitude toward time, the person picking us up was beginning to wonder when she should retreat to Chinle and notify the tribal police.

For the three of us who had hiked into the canyon that day, the experience couldn’t have been more perfect. We climbed down a rocky trail, walked beside a meandering creek, passed rock art from many different eras—that which they call “historic” as well as that which is labeled “prehistoric”—and were surprised by a number of ruins, some of which we had never heard of. Sometimes we were stopped by barbed wire fences, and simply lowered ourselves to shimmy beneath them. The stories our guide told, from his own life as well as from the Canyon’s official history, were by turns horrifying and exultant, poignant and courageous.

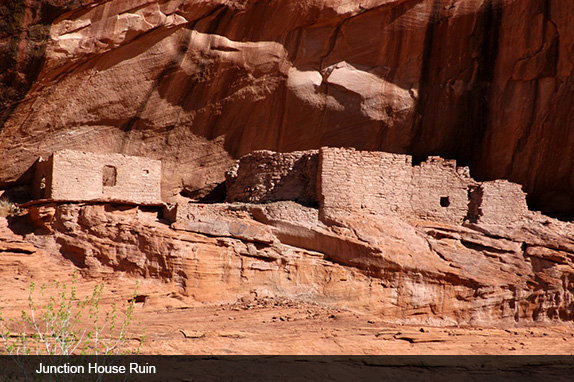

Canyon de Chelly has seen human habitation for centuries. There is evidence from the Basket Maker II period (1,500 BC to 400 AD), from Basket Maker III (400 to 700 AD), and from Pueblo I, II, and III (700 to 1,300 AD). During what we call Pueblo IV (1,300 to 1,600 AD) Ancestral Puebloans built more complex buildings in alcoves and on ledges throughout these canyons. The stonework they employed is related to what we find at Chaco and other area sites.

The Navajo are thought to have entered the area in the mid-1700s. A Spanish map, drawn in 1776, clearly shows the existence of Canyon de Chelly. And it’s from this time that the Navajo began to be hunted, first by Spanish colonial incursions and then by the nascent US government.

The Spanish tried to bring the Navajos under their control by offering them bribes to live by their rules. When that failed, they sent punitive expeditions to track and capture them. One of the most famous, and tragic, of these expeditions took place in 1805. It was lead by Lieutenant Antonio Narbona, later to become governor of the province of New Mexico. Narbona’s official battle report listed the killing of 90 warriors and 25 women and children, who had sought refuge on a deep rock shelf near the top of a wall in Canyon del Muerto. He also reported having captured eight adults and 22 children. The scene of this carnage is called Massacre Cave. I have stood just above the spot, and also looked up at it from the canyon floor. Both times I could feel the horror and fear. It lingers through the centuries.

In 1848 this part of the Southwest came under US control. Now it was the young nation’s turn to try to control the Navajos. Brigadier General James H. Carleton, Commander of the Department of New Mexico and a veteran Indian fighter, believed the only way to pacify the rebels was to round them up and educate in them in the manner of the white man. He charged Colonel Christopher “Kit” Carson with taking 800 men of the New Mexico Volunteers and 200 Ute guides, and setting about to destroy the Navajos’ flocks, fields, orchards and homes. The idea was to force their surrender. The Navajos of Canyon de Chelly believed they were safe among the red-rock walls, and penetration of the canyon was a terrible blow. Great death and destruction resulted from this calculated attack, and only about 100 prisoners were taken alive. Over the next months, many Navajos who had been hiding from their attackers gave up and turned themselves in, broken in body and spirit.

The army established a 40-square-mile reservation at Fort Sumner, 300 miles from the Canyons. Thus began “The Long Walk” to Bosque Redondo. There were only enough wagons and horses for the aged, infirm and very young; everyone else had to make the trek by foot. The governor of New Mexico proclaimed “the Indian problem” over. The US government made many unkept promises, including the apportionment of land, livestock, education, and more. Many treaties were signed and broken. The Long Walk and the experiment at Bosque Redondo decimated the Navajo people, but it also got them to think of themselves as “a people” rather than as disparate bands. Still, those four years of captivity and exploitation marked the Navajo in profound ways. Recovery was long and painful. It is undoubtedly still going on today.

Today the Navajo Nation is the largest semi-autonomous Indian nation in the United States. The people have continued to suffer from poverty, the ongoing health problems that come from uranium mining, unfair federal laws, paternalism, stock reduction policies in the 1930s, alcoholism, hopelessness, and many other ills. Their beautiful homelands, magnets for visitors from throughout the world, often do not even provide them a decent living.

The trading post network that began in the final decades of the 19th century encouraged the great silverwork and weaving for which the Navajos are known. The first license to operate a trading post was issued to Lorenzo Hubbell and C. N. Cotton in 1886. Hubbell’s became one of the most important trading posts in the Southwest. It had its first incarnation at Canyon de Chelly and continues to operate about 45 minutes away—although no longer under the guidance of its legendary trader, Billy Malone.

Today many Navajos get university degrees; Diné College, located in Tsaile, Arizona, serves the residents of the 26,000 square-mile Navajo Nation spread over Arizona, New Mexico and Utah. This is only one of 37 Navajo institutions of higher learning, and of course there are also Navajo students at many non-Indian colleges. Navajos are in every profession. The famous Navajo Code Talkers played an important role in helping the US win World War II.

A relatively recent decision by the tribal council at Window Rock authorized casinos on the Navajo Nation; watching other tribes make money from gambling apparently became too seductive to resist. At Canyon de Chelly, though, the presence of casinos and other accommodation to contemporary living is nowhere to be seen. So Navajo people live in the old ways, tending their sheep, spinning wool and weaving. And young Navajos bear all the contradictions of young people of other ethnicities, with the added burden of biculturalism—and the added don of an unbroken spirituality from a legacy of resistance and creativity.

These contradictions as well as this legacy of rebellion, resistance and beauty, all come together at Canyon de Chelly. Men and women whose families have made their homes in the canyons for generations share their heritage with the visitor. Even the lodging at the Canyon rim is not what it appears at first glance. Thunderbird Lodge, the oldest and most traditional of the hotels, has long been in Navajo hands. The premises are richly decorated with splendid old rugs and pottery. But even the local Holiday Inn is Navajo-owned and extremely pleasant. Its restaurant serves Indian favorites along with continental cuisine, and it sometimes offers two nights for the price of one or other package deals that make a couple of days stay more reasonable.

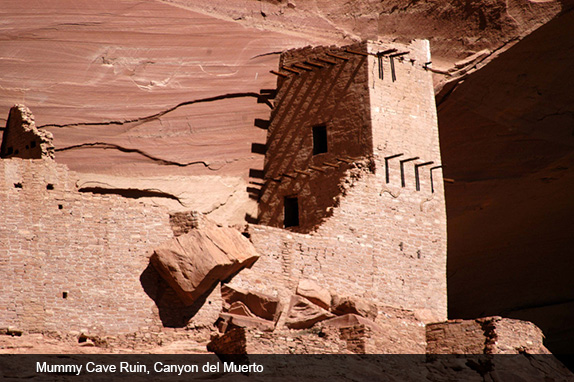

As for the Ancestral Puebloan ruins in the Canyon complex, they have suffered and benefited from the usual history of anthropological discovery, interest, excavation, and preservation. Fairly accurate descriptions of some of the ruins that predated the Navajos were made soon after the US military’s attacks on the people. We have a record of reconnaissance of part of Canyon de Chelly dating to 1849. It was made by Lieutenant James H. Simpson of the Corps of Topographical Engineers. He mentions Casa Blanca, the one site visitors are allowed to hike to without a guide.

The 1873 Wheeler Survey located 140 separate ruins in Canyon de Chelly. Some of the human remains and artifacts collected during that survey ended up at the Smithsonian. In the early years of the 20th century, looting ruins became a common practice. When anthropologists studied some of this material, which found its way to the Brooklyn Museum, they noticed a number of Hopi relics. This was the first indication in scholarly literature that Hopi people too may once have lived at Canyon de Chelly.

Earl Morris conducted an extensive excavation program in both Canyon de Chelly and Canyon del Muerto from 1923 to 1929. During the 1930s many of the major ruins in the canyons were finally dated from tree ring specimens. The dates confirmed what scholars like Morris had determined through other means. From the 1950s on, the National Park Service has run a series of stabilization projects to strengthen and preserve ruins such as Mummy Cave, White House, Antelope House, and Sliding Rock Ruin. These and other ruins in the canyons can be visited today thanks to these efforts.

But Canyon de Chelly is not only about ruins. It contains some of the most spectacular scenery in the Southwestern United States. A particularly magnificent formation is Spider Rock, an 800-foot tall sandstone monolith formed over 230 million years ago. According to Diné mythology, Spider Rock is the home of Spider Woman. When the Navajo came into the present day fourth world from the third, the fourth world was filled with monsters who killed many of the new arrivals. Spider Woman used her supernatural powers to send Monster-Slayer and Child-Born-of-Water in search of their father, Sun-God. He showed them how to destroy the monsters. Spider Woman chose the top of Spider Rock as her permanent home. She is a teacher of weaving; her husband, Spider Man, constructed the first loom using sky and earth cords for the cross poles, sun rays for the warp sticks, rock crystal and sheet lightning for other parts of the loom, and a sun halo for the batten. The comb was fashioned from a white shell. Spider Woman’s other function in Diné society is to enforce obedience in children. They are told that if they do not behave Spider Woman will carry them away.

Canyon de Chelly is a place to go when you need to glimpse what once was and can be again, a place where hardship and terror have left their mark but the mark of a people retrieving their culture is stronger than every attempt at eradication.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Canyon de Chelly”