In a time of increased economic hardship, enclaves of violence as far away as Syria or as close as the streets of Albuquerque, and problems as complex and seemingly insurmountable as climate change, it’s understandable that we long to be transported to an enchanted land where everything is picture-book perfect and we can forget our cares for a while.

Such a place exists. It is called Bryce Canyon, and it’s tucked away in the southwestern corner of Utah, one long or two easy day’s drive from Albuquerque.

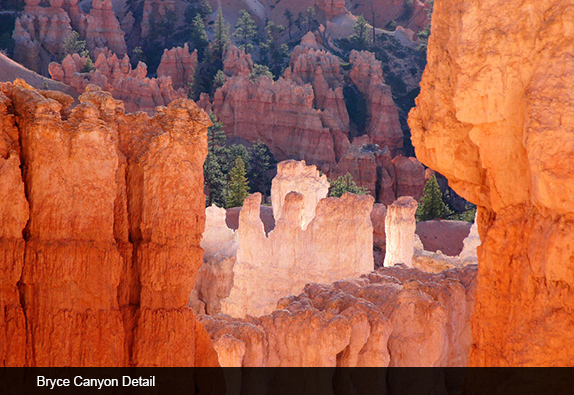

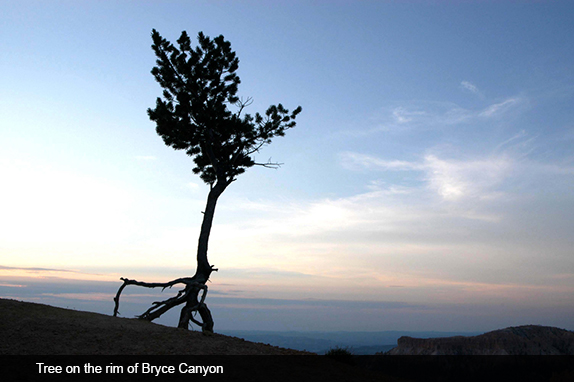

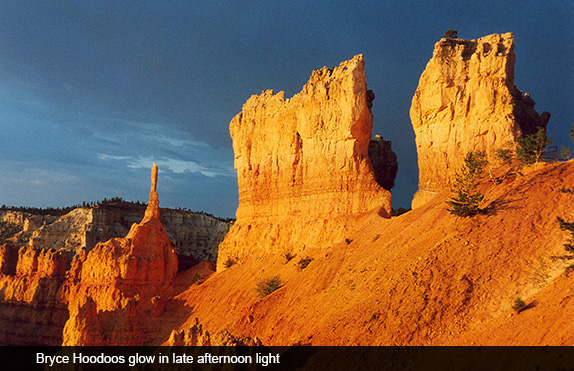

Bryce is not really a canyon, not in the conventional sense of that word. No river carved its magical hoodoos (fanciful rock pinnacles); rather, other sorts of erosion formed its 20 square miles of spectacular landscape. It is a collection of giant natural amphitheaters stair-stepped in brilliant clusters along the eastern edge of the Paunsaugunt Plateau. It looks ancient, yet in geologic terms—and compared with Grand Canyon and other formations that took billions of years to create, Bryce is a product of the much more recent Cenozoic age: millions rather than billions of years made it what it is today. Age at Bryce may best be exemplified by the existence of its many Bristlecone Pines, the oldest tree on the Continent and one of the oldest in the world. Some of the marvelously gnarled Bristlecones at Bryce were seedlings 5,000 years ago.

The area’s pink, orange, purple, warm rust and multi-toned cream display evokes a feeling of warmth, even heat. Yet once again Bryce defies appearance. A thousand feet higher than nearby Zion, at the altitude of fir and pine, it maintains a comfortably cool climate, averaging single digit temperatures in winter and hovering in the mid-eighties during the summer months. As a desert destination, it also receives an unusual amount of precipitation: 15 to 18 inches of rain a year. These unusual climactic conditions make it lush in a way many other parts of the Colorado Plateau are not.

The Bryce Canyon area displays a record of deposition that spans from the later Cretaceous to the first half of the Cenozoic. The ancient sedimentary environment varies in the region around what is now the Park. Dakota Sandstone and Tropic Shale were laid down in the warm shallow waters of the Cretaceous Seaway, which advanced and retreated, advanced and retreated. The colorful Claron Formation, from which the delicate hoodoos are shaped, layered as sediments in a system of cool streams and lakes that existed from around 63 to 40 million years ago (from the Paleocene to the Eocene). As these lakes deepened or dried, and their shorelines and river deltas migrated, different sediment types were deposited. All this upheaval and movement, displacement and further layering, created the wonderland we see today.

Bryce is an intimate jewel, from which you can nonetheless see a vast stretch in every direction. From Rainbow Point, its highest elevation at 9,105 feet and the farthest stop on its 18-mile scenic drive, you can look out at the Aquarius Plateau, the Henry Mountains, and the Vermillion and White Cliffs, as well as many of the spectacular features within the Park itself. Visitors driving this road are encouraged to bypass all points of interest on the way out, then to return exploring them all. Traffic is limited to 35 miles per hour, and following this suggestion eliminates the need to cross in front of oncoming cars in order to pull into the parking lots or take the numerous access roads to each of the breathtaking lookouts.

As is true of much of our country, humans have inhabited the area in and around Bryce for millennia; archeological surveys have found evidence of life going back 10,000 years. Basketmaker Ancestral Puebloan artifacts have been found just south of the Park. The Fremont people (from around mid-12th century) have left numerous rock art sites. Later inhabitants include Paiute Indians, who are thought to have moved into the area around the same time the earlier cultures abandoned it. It was the Paiutes who popularized their own version of Lot’s wife being transformed into a pillar of salt; they say that the hoodoos were the Legend People whom the trickster Coyote turned to stone.

This is rugged country, and it wasn’t until the late 18th and early 19th centuries that the first European Americans explored the remote and hard to reach area. Mormon scouts arrived at Bryce and environs in the 1850s with an eye toward determining its potential for agriculture, grazing, and the establishment of communities. Major John Wesley Powell, the same who became the first White man to run the length of the Colorado River through Grand Canyon, led the first major scientific expedition to the area in 1872. Small groups of Mormon pioneers followed. In 1873 the Kanarra Cattle Company began using the land for grazing.

In the early 1880s, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sent Scottish immigrant Ebenezer Bryce and his wife Mary to settle in the Paria Valley. Bryce was a carpenter, and the Church thought his skills would be useful there. The Bryce family built their log cabin right below what we know today as Bryce Canyon Amphitheater. Ebenezer grazed his cattle inside what are now Park boundaries, and is often quoted as having declared the amphitheater “a helluva place to lose a cow.” He improved local conditions by building an access road and a canal for crop irrigation. Because of these contributions, other settlers began calling the place Bryce’s Canyon, later shortened to Bryce Canyon.

As Mormons settled some of the rugged corners of what would later became the state of Utah, the Union Pacific and Santa Fe Railways were beginning to bring easterners to the great unexplored West. Railway magazines began publishing descriptive articles lauding the area’s great natural beauty. By the early 1920s, the Union Pacific was interested in expanding rail service into southwestern Utah to accommodate a larger number of tourists. In 1923, President Warren G. Harding declared Bryce a National Monument. A road was constructed that same year, to provide easy access to the outlooks from which visitors could view the amphitheaters.

In 1924-25, Bryce Canyon Lodge was built from local timber and stone. Its architect and interior designer was Gilbert Stanley Underwood, the same who created such imposing and well-loved hotels as Yellowstone’s Old Faithful and Jackson Lake Lodge in the Grand Tetons. Its guest rooms have been updated since, but the lodge’s lobby retains its signature grand fireplace and impressive beam work. In 1928, after the government added several additional tracts to the original land designation, Bryce was made a full-fledged National Park.

A word about Bryce Canyon Lodge. If you can, I recommend staying there and eating in its dining room, although both require reservations, a room at the lodge many months in advance. Or, if this is not within your price range, get a space at one of the Park’s two campgrounds. The point is to be as close to the scenic wonderland as possible, to be able to view it in all lights, to amble from where you are staying to watch the sun rise and set on the landscape of hoodoos. If your trip to Bryce is last minute, or there are neither rooms at the lodge nor spaces at the campground, there are other options just outside the Park. The tiny town of Tropic, about 6 miles away, has a smattering of decent motels.

Even closer is Ruby’s Inn, an enormous Disneyland-like complex with 114 rooms, a restaurant, general store, and copies of the Book of Mormon in 17 different languages prominently displayed throughout the kitschy lobby. Ruby’s can be a lifesaver, as its large garage was once for us when we limped in with a flat tire that needed to be patched. We had attempted a notorious road we hoped would take us to a remote trailhead, and blew a tire halfway there. Ruby’s was the only place within a hundred miles we could have gotten that tire fixed. But staying at Ruby’s, which we’ve also had to do from time to time, wars with the experience of those pristine amphitheaters. The Mormons undoubtedly contributed to what today is the state of Utah, bringing agriculture, history and community. Their tradition of proselytization, however, remains a painful thorn.

Throughout and around Bryce there is a wealth of flora and fauna. The lower elevations are dominated by dwarf forests of Piñon and Juniper, interspersed with Manzanita, Serviceberry, and Antelope Bitterbrush. Aspen, Cottonwood, Water Birch and Willow grow along the streams. Ponderosa Pine forests cover the mid-elevations. As you climb the Pausaugunt Plateau, you see large stands of Aspen and Engelmann Spruce. Spring brings abundant wildflowers, sometimes in great patches along the roads.

Bryce’s forests and meadows are home to mule deer, Utah prairie dogs, ground squirrels, marmots, and even California Condors. Of the 170 bird species, many migrate to warmer regions in the winter months, but jays, ravens, nuthatches, eagles and owls stay around. Resident reptiles include the Great Basin Rattlesnake, Short-horned Lizard, Side-blotched Lizard, Striped Whipsnake, and Tiger Salamander.

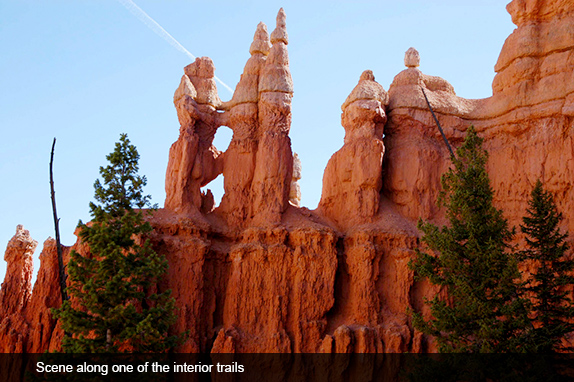

At Grand Canyon, Copper Canyon, and other of the earth’s great natural chasms, most visitors content themselves with gazing into the abyss from above. The fortunate or hardy few venture onto the trails that take them into their interiors. It’s certainly possible to remain above the rim at Bryce as well; I’ve already mentioned the well-planned scenic drive that allows you to stop at a series of spectacular overlooks. But Bryce has the added advantage of trails for every physical fitness level. Even those with disabilities can enjoy the paved stretch of rim trail between Sunrise and Sunset Points.

Perhaps the Park’s most popular trail is Navajo Loop, which switchbacks from the rim down to the Canyon floor, bordered by fantastic rock formations, gnarled roots of old trees, and the stately immensity of tall firs. This trail takes visitors down the rim from Sunset Point, through the narrow corridors of Wall Street, past the Silent City, past an intersection with Queens Garden Loop Trail, and the top of Peekaboo Loop Trail, before ascending the rim of the amphitheater again at Sunset Point. Hikers must descend 800 feet down the side of the Bryce rim, and then at the end of the hike to climb back up. This 1.8 miles trail allows a visitor with limited time to experience the hoodoo embrace in one to 2 hours.

Other easy to moderate trails are Mossy Cave, Bristlecone Loop, Queens Gardens, none of them requiring more than 2 or 3 hours. More strenuous hikes include Fairyland and Peekaboo Loops. I did 8 miles of the latter several years ago, and count it among my most treasured outdoor experiences. I took my time, exploring a part of the Park that receives few visitors. In fact, during my entire 6 or 7 hours in that spectacular backcountry, I only encountered one other hiker. We came upon one another walking in opposite directions as each of us rounded a bend in the trail. Surprise turned to laughter for us both. Bryce also has two trails meant for overnight hiking, the 9-mile Riggs Spring Loop and the 23-mile Under the Rim Trail. These require backcountry camping permits.

Half- and full-day horseback trips may be taken at Bryce, but I don’t recommend them. I looked forward to sitting on a horse, hands free, in order to do some photography without having to hike. It was hot and dusty the day we chose to enter the amphitheaters mounted on those stoic animals. But the biggest disappointment was that we rode nowhere near those parts of the Park where you come in intimate contact with the hoodoos.

One little known and glorious attribute of Bryce is its location far from cities and large towns. This provides the Park with a 7.4 magnitude night sky, one of the darkest in North America. Stargazers can see 7,500 glittering celestial bodies with the naked eye—not that anyone’s counting!—while light pollution in most places reduces that number to around 2,000. In large cities, in fact, only a few dozen stars are visible. You don’t even have to be particularly interested in astronomy to appreciate this feature. If you are searching for a momentary escape from the seemingly insoluble problems contemporary society throws our way, connecting with the calcium of stars goes a long way toward reconnecting with the calcium of which we are made.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Bryce Canyon”