November, 2012. We were traveling through El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala and Belize, following one of the many Maya Routes (ancient Maya ruins exist throughout those countries and the southern part of Mexico, with new sites discovered all the time). At the magnificent ancient city of Tikal, in Guatemala’s Petén, locals approached us as they frequently did: “When you go home,” they pleaded, “please tell your country people not to worry; the world is not going to end!”

They were determined to get this message across for several reasons. Most importantly, they simply wanted people to know that the end of the current baktún, or calendric period, did not mean the end of life as we know it but simply the beginning of the next period. And they were angry because space at the government’s lavish “sound and light” show, planned for December 21st in Tikal’s central plaza, came with a ticket price; those for whom that plaza is sacred space would not be able to afford to attend.

The basis of the Maya Calendar was the count of 260 days, the result of the never-ending permutation of 13 numbers with a rigid sequence of 20 named days. Bars and dots are used for the numbers, a dot standing for one and a bar for five. There are many speculations about the origin of such a period (for example, it approximates the 9-month period of human gestation), but you can visit Maya villages today in the Guatemalan highlands where the calendar priests can still give you the correct day in the 260-day count. It has remained the same for over 25 centuries. This is the Calendar Round. It consists of two interlocking cycles. One is that of the 260 days. Every day has its omens and associations. Trained Day Keepers interpret these signs for the people of their communities.

Meshing with the 260-day count is another calendar, known as the “vague year,” Long Count or Haab. It enumerates our familiar 365 days. This way of keeping time was already widely known throughout the lowland country of what we call Mesoamerica, but the Maya carried it to its highest degree of refinement. The Maya were geniuses in many areas, not the least of these being mathematics. They are credited with having invented the concept of zero.

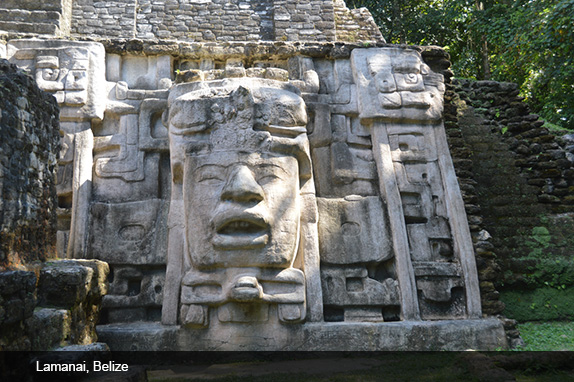

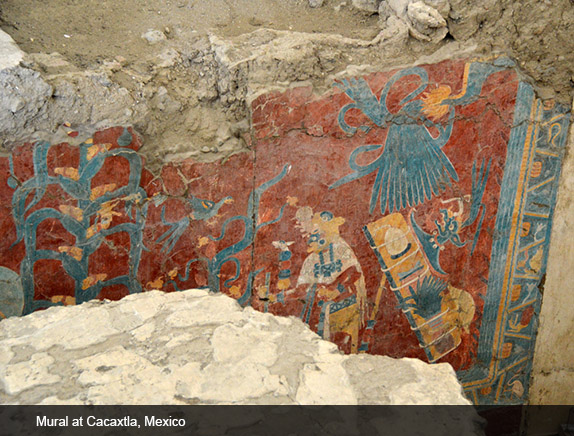

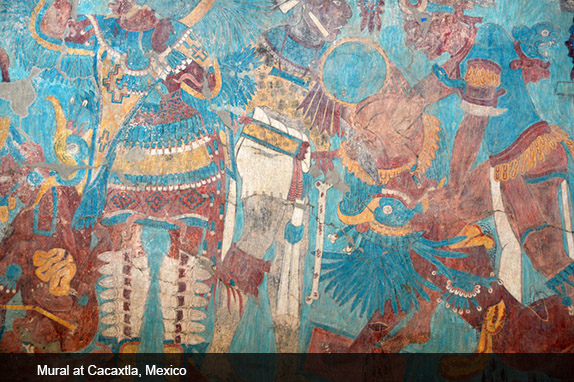

I have visited Maya sites throughout Central America and southern Mexico over a period of many years: Palenque in Chiapas; Chichén-Itzá, Cobá and Tulúm in the Yucatan; El Tajín, Xochicalco and the vibrant frescos at Cacaxtla; Tikal, Quirigua and Yaxhá in Guatemala; the Asiatic-looking faces on the stela at Copán, Honduras. And I have not even scratched the surface. Even as I write, today’s news brings a report of another recently discovered site in the rainforest of eastern Mexico. It is called Cactún, and 40,000 people may have inhabited it from 600 to 900 AD. Such sites are unearthed at least several times a month.

On this trip I would add an earlier and more primitive ruin to my list: Joya de Cerén in El Salvador. Rather than the monumental stone of the better-known sites, this one was constructed of adobe. A succession of volcanic explosions caused Joya de Cerén’s abandonment, but layers of earth and lava teach us about how people lived there. I have long been fascinated by the sites of ancient community throughout the world. But the Maya evoke in me a special sense of connection. And so I have also read everything I have been able to get my hands on about these extraordinary people. Eight million of them, inheritors of a magnificent legacy, continue to live in the villages, towns and cities that dot southern Mexico and countries farther south.

The origins of the Maya are still shrouded in mystery. Some scholars believe their ancestors traveled south from Siberia across the Bering Strait land bridge some 14,000 years ago. Others point to evidence of Mesoamerican settlement as early as 18,000 BC. Radiocarbon dating has identified groups of hunter-gatherers around 11,000 before our era. One of the earliest known artifacts from Maya country is a small projectile point of obsidian found by a picnicking schoolboy at San Rafael in the hills just west of Guatemala City. It is very similar to our own Clovis point. An earlier generation of Maya scholars, particularly Sylvanus G. Morley, believed the May were the first to domesticate corn. And the proto-Mayan language (there are 30 Maya languages today) was spoken before 2000 BC, well within the Archaic Period.

Although survivors of the Spanish Conquest (often described as the most devastating holocaust in history, in which 90% of the native population perished), and the ongoing cultural devastation, policies of extermination, racism, and impoverishment still aimed at indigenous peoples, Maya innovation and resistance have been extraordinary. As architects they are unsurpassed. One has only to consider the monumental pyramids of Tikal, rising hundreds of feet above the jungle. And these marvels were constructed without any of today’s machinery or engineering tools. Maya statuary, ceramics, and jewelry show a genius in design as well as in their use of materials.

As for classic Maya literature, the Popol Vuh rivals the Christian Bible or any other sacred book in its literary claim. In this creation story, the gods fashioned humans first from mud, then from wood, and then from flesh—but all failed to thrive. Finally the gods turned to maize, or corn, as the material capable of producing viable humans. These were their ancestors; they are People of Corn. The codices, or great illuminated books hand-written and painted on accordion-like parchment pages, hold their own beside the books of any other culture. Tragically, the Spanish burned as many of these codices as they could find. Only five remain, and these in a partial or damaged state.

The Maya are credited with having produced the first chocolate. Early on, they survived by discovering that adding white lime and water to ground corn, they could make nixtamal, which continues to be the basis for tortillas throughout modern-day Mesoamerica. Nixtamal’s importance cannot be overemphasized. Maize is naturally deficient in essential amino acids and niacin. A population whose diet consisted solely of untreated maize would have developed pellagra, been malnourished, and could not have survived. Cooking with lime enhances the balance of essential amino acids and frees the otherwise unavailable niacin. Without the invention of this complex technique, no settled life in Mesoamerica would have been possible. Sadly, for these People of Corn, modern genetic modification of the plant is now playing havoc with their traditions and dangerously disrupting their life.

Another interesting piece of Maya dynastic history is the fact that the long lines of rulers, honored in hieroglyphic tableaus at many of the ancient cities, include a number of women. These histories emphasize wars and conquest, and male leaders are in the majority. But names such as Lady Jaguar Shark, Lady Yohl Ik’nal, and Lady Six Sky are scattered among them, piquing our curiosity as to who they were and how they ruled.

The Maya continue to preserve their traditions, passing them from one generation to the next. The Spanish Church burned their books and prohibited their intricate writing, yet in recent phases of scholarly decipherment Mayan scribes were able to help rediscover the meaning of many hieroglyphics. Decades of government violence in Guatemala uprooted them from their traditional lands and decimated their numbers. In Mexico and Honduras, gangs and narco cartels have brought uncertainty into their villages.

Often prevented from acquiring an education by marginalization and poverty, many present day Maya have nonetheless struggled to reinsert themselves into the arena of scholarship pertinent to their own history. Rigoberta Menchú, a Maya woman from the highlands of Guatemala, was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1992. Her personal story, told in the book I, Rigoberta Menchú, put a human face on Guatemala’s 30 years of extreme institutional violence, in which 40,000 were uprooted, tortured, disappeared and murdered.

And in the southern Mexican state of Chiapas, on January 1, 1994, a group of Lacandon Maya now known as Zapatistas (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional, or EZLN) made its appearance. Since then it has remained a vital force, fighting for autonomy not only for themselves but all Mexico’s indigenous peoples. Zapatista leader, mestizo and university educated Subcomandante Marcos, periodically speaks for the group’s ancient consensus decision making and other ideas. One of the things that makes the Zapatistas different from other liberation movements is that it is not fighting for state power.

Knowledge about the Maya has revealed itself slowly, and not without contradictions and setbacks. As a poet, I am fascinated with the still unfolding history of deciphering Mayan writing. This has often been referred to as “breaking the Maya code.” The endeavor has spanned centuries and continents, and breakthroughs have come from scholars of many disciplines, artists, adventurers, and even children. Astonishingly, two Russians—Yuri Valentinovich Knorosov and Tatiana Proskouriakoff—, trained in the Soviet era and greatly limited by its repressive insularity, contributed in fundamental ways to an eventual breakthrough.

This is a story worth repeating, for what it teaches us about the pomposity of preconceived ideas, a paternalistic disregard for the achievements of peoples considered “primitive,” the narrowness of anti-Communist prejudice, and eminences who may in fact turn out to be “emperors without clothes.”

For many years, British Sir Eric Thompson was considered the authority among those studying Maya writing. He had no university degree nor did he hold a post at any institution of higher learning. But he read in anthropology for a year at Cambridge and came to dominate modern Maya studies through the sheer force of his intellect and personality. In 1926 he accepted a position at Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, and from there influenced generations of Maya scholars. Thompson eventually concentrated on deciphering non-calendric Maya symbols. The story of his ideas and interaction with other Mayanists is long and complex. Some of his ideas, in fact, were real contributions. But his own shortcomings—both scholarly and ideological—prevented him from seeing the forest for the trees.

The first real breakthrough in deciphering the Maya Code came from the least likely of places. The Soviet Union, under Stalin, was a place of intellectual repression; anyone who went against the dictator’s ideas could find him or herself banished to the gulag or worse. Scholarly innovation was almost impossible. Yet it was in these restrictive circumstances, in 1952, that Yuri Valentinovich Knosorov, a 30-year-old investigator at Leningrad’s Institute of Ethnology, published an article called “Ancient Writing of Central America.”

In the Marxist state, Knosorov had received an excellent undergraduate and graduate education. He studied many different forms of writing, including Sumerian, Chinese, Japanese, and Arabic. His professors urged him to concentrate on Egyptology. But his interests were more wide-ranging, and also comparative (the latter is what eventually enabled him to contest Thompson’s assumptions). In 1947, Knosorov’s teacher, Sergei Aleksandrovich Tokarev, posed a question to his pupil: “If you believe that any writing system produced by humans can be read by humans, why don’t you try to crack the Maya system?” Knosorov set about to learn Spanish, and devoted the rest of his life to doing just that. His accomplishment is all the more extraordinary if we take into account that not until he was an old man, when Gorbachev finally loosened restrictions on travel, was he able to travel to Central America, contemplate the great cities of Palenque and Tikal, and touch the stone of a Maya inscription. Before then, his knowledge of the field came exclusively from photographs.

At the time, the Maya establishment accepted Thomson’s ideas, which emanated from a paternalistic and Eurocentric inability to assign the people who made the glyphs the intellectual complexity required to have created anything but random images. A few scholars, however, among them Michael Coe (long regarded as the supreme historiographer of Maya studies), read Knosorov’s article and were excited by it. The Russian accepted the prevailing notion that the glyphs represented sounds, or syllables. But, based on his broad knowledge of scripts from other parts of the world, he knew the signs could have more than one function, understood that they might sometimes be inverted for calligraphic purposes, and that phonetic signs might sometimes be added to morphemic ones to lessen ambiguity in the reading. Knosorov compared some of the texts in the codices with the pictures that accompany them. In his groundbreaking article, he concluded: “the system of Maya writing is typically hieroglyphic and in its principles of writing does not differ from known hieroglyphic systems.”

For very different reasons, Fray Diego de Landa, the Franciscan bishop of Yucatan who had been prominent in the Spanish Conquest of Mexico, also contributed to the journey. He had produced an important treatise on the history of the Maya: Relación de las cosas de Yucatán (Account of the Affairs of Yucatan). In his effort to destroy what he considered pagan idols, and the pagan language that described them, he not only burned priceless books and artifacts, but forced Maya scribes to write their language using Spanish letters and sounds. This destruction did nothing less than create a breach between the Maya people and their culture for generations. Yet in the end, Landa’s crime produced what Knosorov recognized as the Maya “Rosetta Stone.” The way those long-ago scribes had rendered their language into acceptable Spanish, provided one of the clues he needed to make his own breakthrough.

Thompson spent most of the rest of his life trying to discredit Knosorov. Cold War ideology bolstered his dismissal. But the great barrier to deciphering the Maya glyphs had been toppled. Fresh minds from a variety of disciplines, no longer stifled by Thompson’s authority, contributed bits and pieces to the puzzle. Another Russian, Tatiana Proskouriakoff, came to the United States with her family in 1915, and thus did not have to face the academic limitations or lack of technology that Knosorov endured. She graduated from a US university in 1930, with a degree in architecture, and ended up on a number of archaeological expeditions to Central America, producing thousands of drawings of pyramid elevations and the glyphs that adorned them. Her great contribution was charting in accurate detail the dynastic records at Piedras Negras. This work, too, was central to the decipherment.

Following these early scholars, there have been dozens of more recent archaeologists, anthropologists, linguists, and other specialists, all of whom contributed in one way or another to breaking the Maya Code. Sylvanus Morley was a bridge to more contemporary minds such as Coe, David Kelley, Floyd Lounsbury, Linda Schele, and George and David Stuart, among others.

David Stuart’s story is fascinating. At the age of 3 he was taken on his first trip to the archaeological wonders of Mexico and Guatemala. His parents spent five months studying the city of Cobá, and he played among the ruins, often with Maya children his own age. On that trip he picked up a number of words in Yucatec Maya. As he got older, and returned on other of his parents’ field trips, he began making drawings of the glyphs. In 1976, back in Washington DC, David met Linda Schele. She was a consultant for a book called The Mysterious Maya, a project being undertaken by his parents for The National Geographic. At one point 11-year-old David, who had been sitting at a table where the adults were working, pointed to one of the pictures and announced: “that’s a fire glyph.” That very evening, Schele invited the boy to spend several weeks with her the following summer at Palenque. She charged him with helping her correct drawings of the important inscriptions at that site.

An unusual and extraordinarily positive aspect of contemporary Maya studies is that it has brought together people from many different disciplines—and even some adventurers who do not call themselves scholars—and has held meetings at which old and young, professors and disciples, people in fields that ordinarily would not pay much attention to one another, all listen to and build upon each other’s ideas. The academic jealousies so detrimental to true scholarship didn’t seem to be present. Linguists, totally disregarded in Thompson’s time, played an important role in the decipherment, which during the 1980s, really began to take off. Since then, it has advanced at a dizzying pace. For those interested in this fascinating history, there is nothing better than Breaking the Maya Code, the feature documentary by David Lebrun. This two-hour film situates the decipherment within the context of our own history and culture in a way that allows us to follow it as if we ourselves were intimately involved. Through digital animation, we can trace the development and decipherment of a single glyph.

Many exciting discoveries in the long journey to decipher Maya writing poke at my poet’s sensibility. One that is particularly interesting involves the fact that ancient Maya scribes didn’t always draw a given glyph in the same way. They often let their imaginations and playfulness run wild. Glyphs have been found hiding within glyphs, an artistic abbreviation of the most creative sort. As noted, there were and are many different Maya languages ranging over a vast territory. The drawing of glyphs also varied from language to language. Some 80 percent of Maya glyphs have now been deciphered, but learning the language is not the same as learning its meaning or how it was spoken. For this, much work remains to be done. It will be through a non-competitive sharing of information and a more complete understanding of the history and culture of the Maya people, that such discovery will be achieved.

As a poet I am fascinated by the differences between oral and written traditions, what part memory plays in language development, how the broader culture influences language and communication, and the roles of such things as memory, the conquest of one people by another, and many other variables. Why are some languages glottalized and others tonal. Why do some use complex rules of grammar and others seem almost grammar-free? At this point in the study of human history, it is more than clear that a people’s cultural or philosophical complexity does not depend on the perceived complexity of its language.

I have never understood the distinction between pre-history and history, which is generally based on the existence of a written language. Images are a type of language to me, including the rock art found everywhere in the world and certainly the glyphs developed by the Maya. Even the Rongorongo boards, found on the island of Rapanui (Easter Island) and bearing lines of repeated symbols not associated with either letters or sounds, define communication. It is believed they once stimulated memory, enabling those who “read” them to refer to certain stories from their traditional past.

The poem is a distillation of such communication.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Breaking the Maya Code”