The fall and winter seasons mute New Mexico’s brilliant land colors and sometimes its cobalt sky as well. Recent years have brought smog to some of the state’s larger urban areas. In Albuquerque’s South Valley, at wildlife refuges such as Bosque del Apache and Sevilleta, and in other parts of the state where migratory birds winter, green fields turn gray and brilliant reds and golds go pale. But these understated tones often provide canvases upon which one may view amazing displays of wildlife activity. It’s all about adjusting the eye to subtlety, and slowing one’s tempo.

Such was our experience on a recent morning at Bosque del Apache, just south of Socorro. The yearly Festival of the Cranes had come and gone. We hadn’t risen early enough to get there in time for dawn’s great liftoff, when the air suddenly fills with one hundred thousand wings. Nor could we stay for evening’s reverse pattern. This was not one of those magical times when mist rises from the water, creating a momentary wonder. Still, many visits have taught us that a visit to the Bosque invariably brings some lovely surprise. We exited I-25 at San Antonio and made our way to the refuge.

After seeing Bosque del Apache in all its majesty—in every season, in its wildest suits of color, and even years back when a few large Whooping Cranes wintered there—our first impression of this quiet late fall morning was disappointing. It was as if a gray blanket covered everything. Great piles of uprooted blackened tamarisks, burnt in an attempt to return the area to its native vegetation, stood like dark sores upon the earth. At first glance, the tans and creams and browns were indistinguishable. Some previously flooded fields had been drained, and were nothing more than empty expanses of sand. Along the South Loop we only saw a few ducks. There was little green, just some patches of brilliant pads in several of the canals. Was this going to turn out to be a wasted visit?

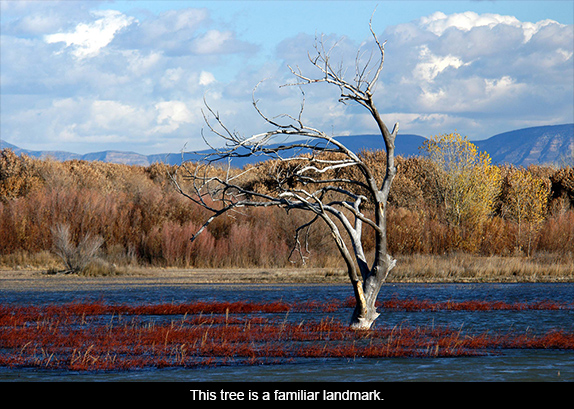

But as we drove slowly, taking in every glimpse of spots that might be hiding aquatic or quietly grazing birds, something interesting happened. The stillness took on its own presence, much like learning a new language. The quiet began to penetrate minds accustomed to city activity and noise. And the colors of the land came out to meet us. Suddenly what had seemed an indistinguishable mass of gray or tan projected dozens and then hundreds of different shades. The yellows turned to burnt umber, orange, pink, and even red. The greens showed tonal differences that took our breath away.

Then, as we drove from the South to the North Loop, the migratory birds appeared—in vast numbers. The daily count at the Visitors Center where we’d stopped on our way in had announced close to 30,000 Sandhill Cranes, almost twice that many Snow Geese, crows, harriers, and even 28 raptors, including Bald and Golden eagles. Here they all were, filling fields from the loop road to the far edge of fields ending at a horizon of purple mountains.

At the Visitor Center for $6 we had picked up a fascinating pocket guide called Sandhill Crane Display Dictionary—What Cranes Say with Their Body Language. According to this guide, the crane’s crown, feathers, posture, wing position, bill, direction of gaze and whether it is walking quickly, pacing carefully, running or flapping its wings, show arousal, the intention of recruiting others to dance, territorial preservation, dominance, or a desire to mate. How the crane stands or moves denotes intent to fly, unison calls, location, vigilance and awareness of threats, jumps that are part of the courtship dance, and bows taken after mating, among others. There are solo dances, minuets that denote the close synchrony of a pair, and family dances. And it’s not only position and type of display that announce a crane’s intention. If one knows what to listen for, the music one hears as continuous clacking from 30,000 throats also breaks down into a variety of calls.

With this compact and easy to follow guide, one can gaze into a field of cranes for hours, noticing ever more complex behaviors and learning to know these extraordinary birds in their full range of activity.

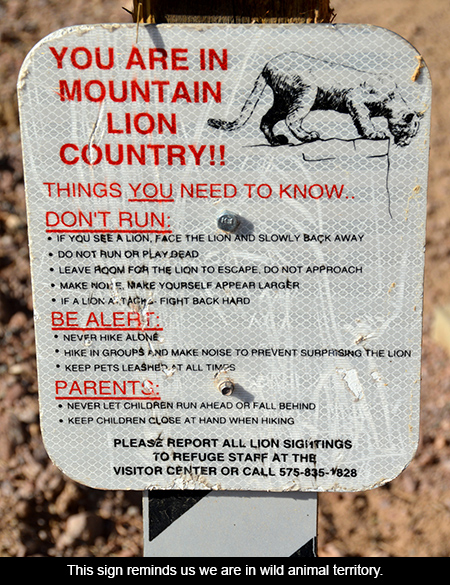

There’s always something new at Bosque del Apache. Following a seven-year drought, the site experienced average precipitation in 2014. This doesn’t mean we are out of danger; the Southwestern United States continues to suffer from a serious lack of water. It does, however, mean that the Bosque has enjoyed a parenthesis, providing it with better wetland habitat, reduced fire dangers, and an unusual display of wildflowers over the past year. Along the southeast side of the North Loop, habitat has been enhanced through earthwork, vegetation clearing, and improved water control. The refuge continues to improve its trails and ditch gates. It is also in the initial phase of testing the viability and seed yield of several varieties of heirloom corn.

Inside the Visitor Center we also found something of interest, a new seal designed by store manager Kim Royle and produced by Black Duck Screen Printing and Embroidery in Albuquerque. The seal can be bought for $5 in the form of a patch that might adorn a cap, shirt, jacket or backpack. As always, there is a good selection of literature, apparel, art, and local jewelry.

Fall and winter landscapes require more from us. We must slow down, get quieter, notice details easily passed over when we are assaulted by richer colors. If we look long, hues we have never seen before settle in our eyes and remind us that nature’s palette is richer than we imagine. The desert and its myriad of secret places is a fantastic place to do this.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Bosque del Apache”