Just 4 miles north of Moab, Utah, Arches National Park delights the visitor with more than 2000 natural sandstone arches in hues that range from deep red to tan and pale cream, as well as many other rock formations. Forty-three of the arches have collapsed since 1970, due to erosion from wind, rain and time. One of these, Wall Arch located along the popular Devil’s Garden Trail, imploded as recently as sometime on August 4th to 5th, 2008. The close to 77,000 acres were designated a National Monument in 1929 and became a Park in 1971. Utah’s license plate displays Delicate Arch, perhaps Utah’s most recognizable landmark.

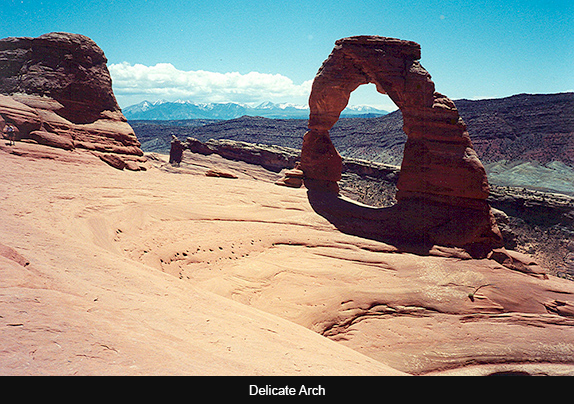

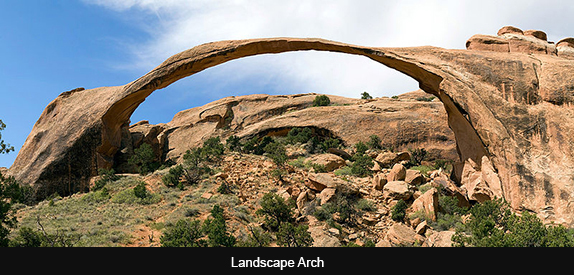

Delicate Arch is less delicate than impressive, crowning as it does a small basin reached by hiking up over a dramatic slickrock rise. Landscape Arch, with its frighteningly thin 290-foot span, is visible along a longer hike further into the Park. It is rumored that these two arches originally bore each other’s names, and that they’re names were mistakenly transposed when documenting the hundreds of labeled features.

Arches lies atop an underground salt bed, and it is the millennial shifting and change in this bed that caused the formation of the arches, spires, balanced rocks, sandstone fins and eroded monoliths that combine to produce this startling landscape. The forces that sculpted the forms we see today read like the work of an artist’s hand in extreme slow motion.

In places, this salt bed is thousands of feet thick. It was deposited approximately 300 million years ago in the Colorado Plateau’s Paradox Basin, when a sea flowed into the region and then slowly began to evaporate. Over the next few million years, this salt bed was covered with debris eroded from the Uncompahgre Uplift to the northeast. During the Early Jurassic, some 210 million years ago, desert conditions prevailed in the region, and the vast layer of Navajo Sandstone was deposited. Then an additional sequence of stream-laid and windblown sediments of Entrada Sandstone layered on top of the Navajo. Over 5,000 feet of the younger sediments have now mostly eroded away.

Remnants of the cover still exist in the area, including exposures of Cretaceous Mancos Shale. The area’s arches are mostly within the Entrada formation. The weight of this cover caused the salt bed below it to liquefy and thrust up layers of rock into salt domes. The evaporation that took place formed more unusual salt anticlines, or linear regions of uplift. Faulting occurred, and whole sections of rock subsided into the areas between the domes. In some places these sections turned almost on edge. The result of one such 2,500-foot displacement, the Moab Fault, can be seen from the visitor center.

As this subsurface movement of salt shaped the landscape, erosion removed the younger rock layers from the surface. Except for isolated remnants, the major formations visible in the Park today are of the salmon-colored Entrada Sandstone in which most of the arches form, and the buff-colored Navajo Sandstone that has given rise to other formations.

Over time, water seeped into the surface cracks, joints, and folds of these layers. Ice formed in the fissures, expanding and putting pressure on surrounding rock, breaking off bits and pieces. Winds later cleaned out the loose particles. A series of freestanding fins remained. Wind and water attacked these fins until, in some, the cementing material gave way and chunks of rock tumbled out. Many damaged fins collapsed. Others, with the right degree of hardness and balance, survived despite their missing sections. These then became the famous arches.

Well-known novelist Edward Abbey worked as a ranger at Arches, and his book Desert Solitaire, based on notes he took at the time, has become a favorite among lovers of Southwestern landscape. It is an interesting read, some would say a passionate read, prior to visiting the Park.

More anonymous human occupation of the region is traceable to the last ice age, 10,000 years ago. Fremont people and Ancestral Puebloans left evidence of their life here up until about 700 years ago. Spanish missionaries encountered Ute and Paiute people in the area when they first came through in 1775. The first European-Americans to attempt settlement were those of the Mormon Elk Mountain Mission in 1855, but they soon gave up and left the area. Some 30 years later, ranchers, farmers and prospectors settled Moab, in the neighboring Riverine Valley. The town took hold, and is today a convenient and welcoming place to stay if you want to visit Arches, Canyonlands, or a number of other nearby destinations. The town has motels and restaurants for every taste, a wealth of art galleries, and companies where you can rent a bike, sign up for an overland 4-wheel-drive tour, or join a one- or two-day float trip on the Colorado River. Moab also has one of the best bookstores in the West: Back of the Beyond.

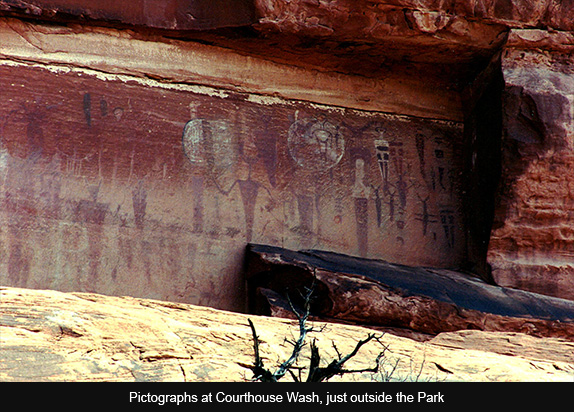

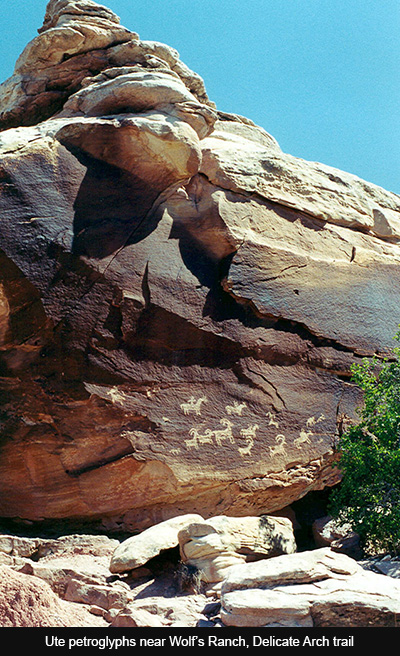

Just after crossing the Colorado and before entering the Park itself, there is a small pullout to the right where you can park your car, walk back a ways, and then climb to a panel of pictographs fairly high on the cliff. If you know where to look, these are visible from the road. Although parts of the panel have sadly been vandalized, these images are worth a close look. Arches must have many such examples of pictographs and petroglyphs, but the only other panel I have seen is the much more recent big horned sheep presumed to have been etched by Ute Indians near the beginning of the hike to Delicate Arch.

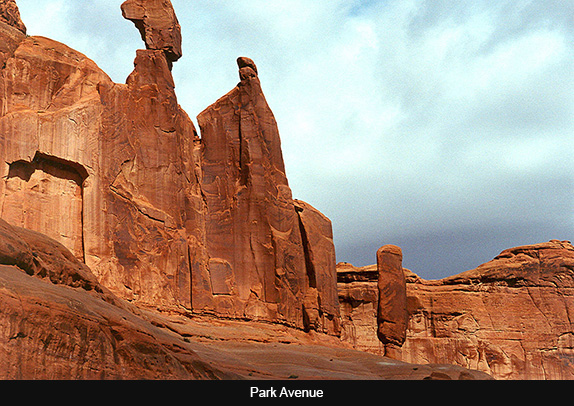

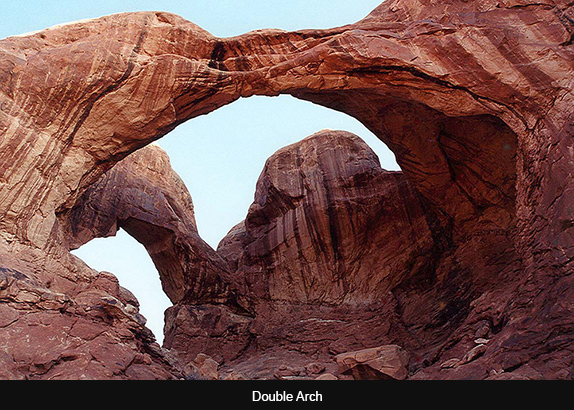

Arches is well designed for any visitor. It can be enjoyed from the window of a car, with occasional stops to photograph one of its many natural rock formations, such as Balanced Rock, a precarious looking tower the size of three school buses, or the collection of tall stone columns called Courthouse Towers. Short strolls offer proximity to other formations, such as Double Arch. One popular 1-mile walk, called Park Avenue, requires a shuttle situation if you don’t want to traverse it in both directions; you can be dropped off at one end and picked up at the other. Walking through Park Avenue allows a profound connection to the tall formations along the way.

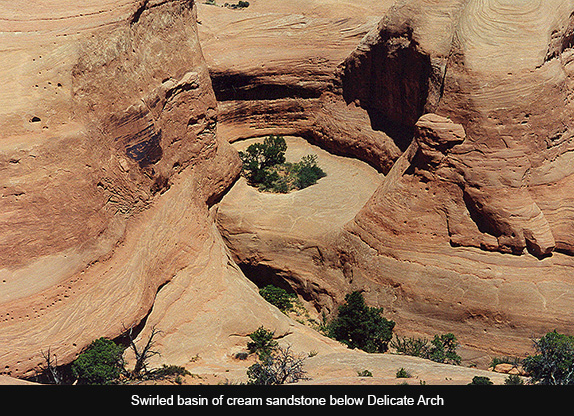

For those who are more adventurous, hiking to Delicate Arch is a must. You leave your car in an ample parking lot, then follow the trail past Wolf’s Ranch (remnants of an early settler’s cabin) and stop to admire the panel of historic petroglyphs left by Utes. The trail continues over a small bridge and then up onto the enormous slickrock dome leading to higher elevations. The scenery in all directions is breathtaking, including the intense swatch of green rock in the near distance that gets its color from copper deposits.

The last ten minutes or so are especially dramatic. You walk along a broad ledge cut into the mountain, then round a corner and glimpse Delicate Arch for the first time. Way down to your left is a swirled basin of creamy sandstone. Close in to your right is the wall you are edging around. Then suddenly, the Arch is before you in all its magnificence. This is a hike that should be savored over two or three hours, and with plenty of water on hand to combat the desert heat.

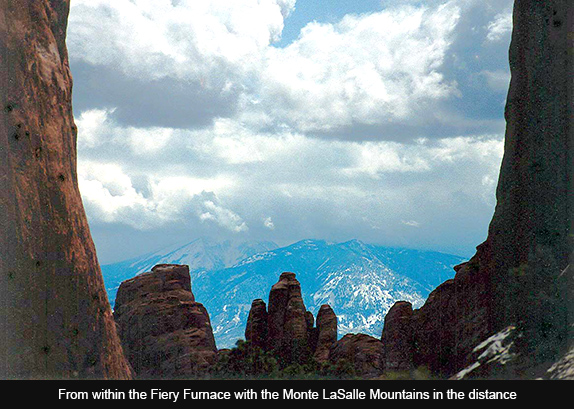

Longer hikes abound in the Park. The one past Landscape Arch also explores the tops of narrow fins and takes you into an area where you may enjoy greater isolation from other visitors. The only hike you must sign up for, and take with a guide, is the one offered twice daily into the maze called The Fiery Furnace. This is a warren of narrow passages and tall rock columns including a few more difficult traverses along ledges and through slots. It is well worth the effort for anyone fit enough. I did it in my sixties, so it’s not really that difficult.

I should note that, seductive as it may seem, Arches is off-limits for those hoping to climb its rock formations. That said, it is a destination for everyone: a giant playground for families with kids—especially kids older than four or five, who are able to do some of the shorter hikes, or those young enough to be carried by their parents—, a romantic wilderness for couples who enjoy exploring unusual landscapes, and ideal for the woman or man hiking alone who appreciates the desert’s solitude.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Arches”