Like Hong Kong in China, Spain’s Catalonia, Chile’s Easter Island, or Hawaii—a US state in the middle of the Pacific—, Alaska is a part of the United States that may have less in common with “the lower 48” than if it were another country. True, the vast territory separated from the mainland by Canada is subject to the same federal laws that govern the rest of us, and the English language dominates. But that may be where the similarities end. I sense you would have to live in Alaska for a number of years before you could begin to imagine that you know it.

Alaskans have a reputation for being fiercely resourceful and independent, much as Vermonters do but facing more rugged and dramatic terrain and cruder natural elements. Headline grabbers like ex-governor and Republican vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin may dominate the news, but most of those in the vast and sparsely inhabited state live more basic, less caricatured lives. At 586,412 square miles, more than twice the size of Texas, Alaska is larger than all but 18 sovereign countries. It has 34,000 miles of tidal shoreline, more than three million lakes, and half of the world’s glaciers—which are shrinking, as they are everywhere. More public land is owned by the federal government (through the National Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management) than in any other state.

The state has the highest mountain in the country, Mt. McKinley. It also has one of the great sporting events of modern times, the Iditarod dog sled race that since 1973 has run from Anchorage north to Nome the first Saturday in March. The word Iditarod is believed to come from the Ingalik and Holikachuk word hidedhod, which means “distant place.”

The Iditerod trail was used for hundreds of years by the Inupiaq and Athabascans as a link among native villages. The trail got a lot of traffic when miners used it during a gold strike in the early 1920s, and it served as the main thoroughfare across Alaska for decades afterward, used for mail delivery, transport of goods, and travel for people moving from village to village—mainly judges and clergymen. In 1978 Congress designated the Iditarod a National Historic Trail.

An event dominated by male “mushers,” women have nonetheless made Iditarod history. Susan Butcher won for the first time in 1986, completing the 1049 hazardous miles in 11 days, 15 hours, five minutes and 13 seconds. She went on to win again in 1987, breaking her own record by more than 13 hours. Then she won again in 1988. And in 1990 she broke her record once more, with a victory an hour faster than the one she’d established previously. I can remember attending a bake sale in support of Butcher at a women’s bookstore in Anchorage in the mid-1980s; many of the male participants had corporate sponsors. The situation reminded me of my generation’s question: “When will the military have to hold a bake sale to buy its B-52s?” Butcher retired to start a family in 1995.

Alaska was purchased from Russia in 1867 for $7.2 million dollars, or approximately 2 cents per acre. It became an incorporated territory in 1912 and the 49th state in the union in 1959. As a state it has no officially defined counties, but there are widely accepted regional demarcations. These include the most highly populated South Central Alaska, with the state’s largest city, Anchorage, and the Kenai Peninsula. The Southeast is also known as the Panhandle or Inside Passage: a popular tourist destination. This area includes the Tongass National Forest, largest in the United States, and the state capitol of Juneau. The Interior is home to Denali National Park and Mt. McKinley, as well as a vast uninhabited wilderness. Fairbanks is the only city in this region, and it is little more than a large village.

The Southwest is another sparsely populated region stretching some 500 miles inland from the Bering Sea. The North Slope is mostly tundra, dotted with small villages. This is the area known for massive reserves of crude oil, so tempting to corporate greed. More than 300 small volcanic islands, which together make up the Aleutians, stretch 1,200 miles out into the Pacific Ocean. The International Date Line was drawn west of 180 degrees in order to keep the state, and thus the North American continent, within the same time zone of a single legal day.

Before the arrival of Europeans, many indigenous peoples had occupied what we now call Alaska for thousands of years. Among these are the Tlingit, a matrilineal group that still resides in the Southeast along with parts of British Columbia and the Yukon; the Haida, known for their exquisite art; the Aleut seafaring society that now inhabits the Aleutians; the Gwich’in who live in the northern Interior and are dependent on the vast herds of caribou that roam free across the much-contested Arctic National Wildlife Refuge; and the Inuit people of the North Slope, among others. These natives have had to contend with Russian, Japanese, and lower 48 colonization. The 2012 census listed a mere 731,449 residents in the state.

As of 2011, slightly more than half of Alaska’s population under one year of age belonged to a minority group, meaning that the state—along with the country as a whole—is rapidly becoming non-white. However, only about 5% of Alaskans speak one of the state’s 22 indigenous languages, indicating the cultural loss we see everywhere.

Alaska offers a sad example of natural beauty and rich cultural life threatened by corporate avarice and its resultant human impoverishment. In 2007 its gross state product was just under $45 billion, 45th in the nation. Its per capita personal income was around $40,000, making it 15th; but this was not indicative of how the struggling native population lives in relative isolation. The oil and gas industries dominate the Alaskan economy, with more than 80% of the state’s revenues derived from petroleum extraction. Exports also include seafood, minerals, and timber. Employment is mainly in civil service, natural resource extraction, shipping, and transportation. Federal subsidies keep taxes low. Tourism is also an important source of income.

Visiting Alaska, unless you are going to see family or have some other personal connection, is like visiting a foreign country. I have friends who have hiked the rugged interior, dependent on a bush plane to pick them up at a pre-arranged spot. When torrential rains caused a river they had to cross to rise so high and run so fast they were unable to get to the other side, they were forced to subsist on plants for a week. Eventually, when he couldn’t find them, the bush pilot realized they must have had to return to their point of departure. The story ended well. Many of us are familiar with the young man whose life expired in an old school bus, or the adventurer who thought he could make friends with grizzlies until one killed and ate him. These are isolated cases, but seem to symbolize the rugged north.

My own forays have been considerably less wild. Up until this decade, all my trips had been invitations to lecture or read my poetry, the sort of brief visit that only whets one’s appetite for more. So in 2010 my partner and I decided to explore the Inside Passage. This can be done in one of three ways. You can hop a succession of local ferries from port to port, by far the least costly and most authentic way to get to know the towns and people in this part of the state. Some ferries sell private cabins; others don’t need to because the run is relatively short. Easily available tours to places of interest allow one to see the sights advertised with the other two choices.

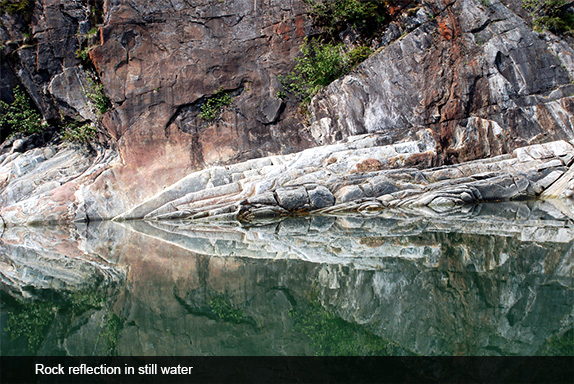

At the other extreme would be booking a place on one of those immense cruise ships that look more like floating cities than like ships. This mode of travel has never appealed to me, less so in Alaska’s Inside Passage where such vessels are much too big to make it into intimate coves or get close to calving glaciers. The third choice is to take a much smaller ship. This was what we did. We worked through a small Alaskan travel agency, and booked space on a boat that can carry 150 passengers but on our trip had only 48. It was perfect for what we wanted. The captain was expert at taking us close enough to sudden waterfalls that we could actually reach over the railing and touch the glistening stone. He maneuvered into ports and as close to glaciers as was safe.

We felt as if we were on an expensive Lindberg or National Geographic cruise at half the price and with far less pretension. As with those companies, experts in a variety of fields came aboard to offer us history, cultural insights, and fascinating conversation. We spent days in coastal villages, visited an eagle preserve, hobnobbed with bear, and orca whales, floated past sea lion colonies, and spotted one baby mountain sheep who had lost its mother and was perched forlornly on a high ledge (another ship’s captain later rescued the orphan, we learned, and brought it safely to the Anchorage zoo).

In Ketchikan we had the opportunity of meeting with native elders and learning about the challenges indigenous Alaskans face. At Metlakatla, we spent a day with a group of natives, who treated us to a meal and series of dances. Our guide was a very young woman, who told me her dream was to study at New York City’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice. In Juneau we happened to arrive just as a yearly gathering of tribes from throughout the state had come together to conference and fill the streets with pageantry and music. Our trip was only two weeks, but we felt we got a taste of this part of our country that seems so foreign and at the same time exerts such a powerful pull.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Alaska”