For as long as I can remember, I wanted to go to Africa. The continent called me like no other. Morocco, where as a young woman I spent time in Tangier’s Kasbah for a while. Jordan’s Petra. Egypt, where the pyramids of Giza disappointed but I found other monuments thrilling. Tunisia’s three deserts. But especially the wild animals I gazed at in books when I was a child. I couldn’t have distinguished their habitats or habits. For years I only paid vague attention to the differences between the many sorts of antelope, or knew what separates apes from monkeys. But Jane Goodall and Diane Fossey were heroes I knew about, among many others.

The idea of a safari bothered me. I knew that the only way someone like myself might be able to visit those animals in their natural habitats would be to sign on to that sort of an adventure. But I resisted its Great White Hunter implications. Only the wealthy could afford that kind of travel. Maybe only the wealthy weren’t bothered. What did the people who live in Kenya and Tanzania, Botswana, Zimbabwe or Namibia really think of visitors with cameras slung around our necks invading their wildlife reserves?

Of course all sorts of rationalizations are possible. Barbara and I discovered a company that brings small groups to the game parks for a relatively modest cost. We would be helping struggling economies we told ourselves. The motto Leave only footprints, take only photographs was reassuring. Visiting and taking only pictures away was surely preferable to engaging in big game hunting. Still, we weren’t convinced. One year we signed up for a trip, even went so far as to get the required shots, and then canceled. Despite the depth of our desire, we couldn’t bring ourselves to go through with it.

Our specially purchased dull brown and green shirts hung idle in our closets. We’d been told they were the most appropriate for viewing animals in the wild, but weren’t what we favored in our Albuquerque lives. Then—I can’t remember or recreate the rationalizations—a few years later we looked at one another and said: “If not now, when?” The truth is, we had the money and chose to use it in this way. We went after all.

The morning we drove out of Nairobi, Kenya, and arrived at our first game park, we both burst into tears. Our open vehicle was suddenly surrounded by zebras, giraffes, and funny-looking warthogs, interacting with one another in ways it is impossible to see in a zoo. They all seemed to regard our group of twelve and our vehicle as being of a piece. Our guide told us that as long as we didn’t get out of the jeep we had nothing to fear from animals respected and protected by their national laws.

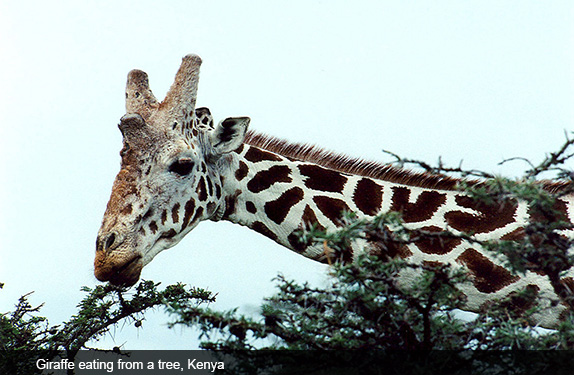

As we moved from Kenya to Tanzania, viewing a lioness teaching her young to eat from a kill, wildebeests locked in mortal combat, a shy leopard hanging out on a low-slung branch, and giraffes eating from the tall tops of trees, our guide put his expert knowledge at our disposal. He could spot a camouflaged animal at a great distance. He taught us to be quiet, to stop our incessant chatter so we would be more likely to discover the secrets of wild animal life.

One of many stories he told us has stayed with me, bringing a sigh every time someone suggests that animals have no emotions. The story was about a friend of his, another wildlife guide. His friend had previously worked at one of the hunting preserves, leading men with guns to places where they would be able to score a proud head or pair of giant horns to display on their walls back home. Years passed, and eventually that preserve ceased welcoming hunters. It became like those we were visiting: a place where people like ourselves traveled to see these magnificent beings on their own turf. Our guide’s friend, because he knew the terrain, was rehired. One day, out with a group, an aged elephant attacked their jeep. The old bull plucked the guide from the vehicle, dragged him a short distance, and killed him. He had no interest in harming any of the other visitors, but remembered the man who, two decades before, had brought hunters there to kill his friends.

At the bottom of Tanzania’s Ngorongoro Crater we witnessed many examples of animal coexistence and cooperation, as well as local Maasai shepherds herding their cattle into the crater for the day. Its grasslands can feed them too.

On a ridge above the Tarangiri Valley, we woke just as dawn was breaking one morning when we heard a ruckus farther down the line of tents. A female elephant had made her way to the rim, and a 14-year-old in our group had mistakenly left his flash on when photographing her. She wasn’t pleased. We had been warned not to use a flash when taking pictures of the animals.

This elephant wasn’t in a forgiving mood. She approached each tent in turn, forcing its by then curious occupants back inside. Ours was the last in the row. By the time she reached us, she was finishing up the lesson. She rumbled right onto the tent’s tiny porch and stuck a menacing trunk through the fly. By this time Barbara and I were huddled in the bathroom at the rear of the tent, behind yet another fly, this one zipped shut. Of course the elephant could have hauled the whole tent off if that had been her intention. She only wanted to prove her point. A few minutes later she was gone.

One night, asleep on the vast Serengeti plain, I woke in the middle of the night to the sound of heavy purring. It sounded very close, like a house cat but magnified a thousand times. Then the breathing was interspersed by low guttural growls, very satisfied ones. The next morning we discovered what it was. A lion had made a kill quite near our tent. The remains of the wildebeest could still be seen, along with the tracks of one adult and several baby lions.

The tents at this particular site were rudimentary, but contained everything we needed. It was there that I got up on another morning and stood brushing my teeth before the small mesh window above the sink. I looked out and noticed a pair of curious eyes looking into mine. The tree overhanging our tent housed a family of baboons. That’s how I learned that the males roost in the highest branches, the babies in the middle, and the females form the first line of defense in the branches closest to the ground.

The Serengeti was also the scene of one of that trip’s greatest adventures. Our group had arrived at another camp, quite a bit more upscale, in an entirely different area of the plain. Generally, when we’d arrive at a camp in the evening, we were greeted with moist towels and something delicious to drink. In a matter of minutes we would be assigned to our tents. This time, however, the wait was prolonged. We wondered what was going on. Finally the camp’s manager appeared and told us, with great embarrassment, that there had been a mix-up. For that night only they were short one tent. Would two of us mind moving somewhere else, just for tonight?

Our group had several members for which this should have been easy. But no one raised his or her hand. One older man, traveling with his wife and three teenaged grandchildren, always slept alone. We all looked at him, but he began mumbling something about wanting what he’d paid for. The camp manager seemed more and more uncomfortable.

Barbara and I looked at one another and raised our hands in unison. What could be so bad about moving somewhere else for one night? Relieved, both the camp manager and our guide loaded our bags back into the jeep and we took off. For a good half hour in the gathering dusk we transited narrow dirt roads, then turned down an even narrower lane at a tiny handwritten sign with the words River Camp etched into the wood.

Much to our amazement, our destination turned out to be an elegant private camp owned by a hotel chain that charges a minimum of $1,000 for an overnight stay. A small group of people, we later learned were celebrities and State Department personnel on leave, sat on a verandah beneath broad umbrellas sipping drinks. The camp manager greeted us: “We are happy to be taking care of you tonight.” In this wilderness camp managers have each other’s backs, eager to solve a problem when the need arises. Then, after our guide promised he would be back for us the next morning, our private butler showed us to our tent.

This camp was situated on the elbow of a small river, filled with hippos. Less than 100 yards separated the camp’s main gathering area from the water. Here the tents were furnished with museum-quality art. Luxury showers had intimate jungle views. We were warned not to walk about on our own, but always to call on our butler who was armed and would happily take us where we needed to go. That night we felt like we were on our second honeymoon. Dinner was exquisite, though conversation with the other guests polite at best.

The next morning they came for us as promised. Back at our original camp other group members applauded our gestire, telling us what an admirable sacrifice we had made. Our tent, now available and freshly made up, was filled with grateful gifts from camp management. We tried not to gloat.

Stellar among the experiences we had, was visiting one of Jane Goodall’s Chimpanzee camps where we floated for several hours along a narrow river. We were caged in our boat, while the chimps along the shore roamed free.

Another hour I will remember was watching a lioness teach her two adolescent daughters to hunt. She was chasing a zebra. When they got within striking distance, she suddenly turned and led them away. Hunger hadn’t driven the pursuit. It had only been a teaching exercise.

A lesson in cooperation may be gleaned from the behavior of wildebeests and zebras, species that enjoy a remarkable relationship. They are perfect companions. Wildebeest are short grass grazers, their mouths shaped so they can grip the juicy shoots. Zebra have long front teeth and can sheer off the long grass. When entering a new area, zebras basically mow the lawn for the wildebeests to enjoy, and then follow up by nipping at the bits left behind. Zebras have good memories and can remember the direction of the migration, the best places to cross the rivers, and so forth. Wildebeests can smell the water before the zebras. They tend to jump in and hope for the best, which is why they are often easy targets for hungry crocodiles. Zebras will watch an individual cross safely before they all charge in. So it's beneficial for wildebeests to be on the march with zebras, since they are the more careful travelers. Wildebeests need to drink at least every other day so they have developed a sense of smell that leads them to its sources. Zebras, on the other hand, have better eyesight and hearing, so they are quicker to sound the alarm when a lion or hyena comes prowling around.

We spent time in Maasai and Bantu villages, interacting with people who live as differently from us as it is possible to imagine. We also spent an hour or two at the museum home of Karen Blitzen, trying to imagine what life was like for that intrepid foreign woman who made Africa her home. Highlights of our experience were visiting a couple of modest country schools, where we talked to the students, enjoyed the music and dance they regaled us with, and even helped buy them the generator that would lift their classroom experience from one level to another. We gazed at Kilimanjaro, and bemoaned the fact that global warming had decimated much of its signature snowcap.

It would take many pages to relay enough of what we experienced to give a full sense of how Africa changed me. I have never since visited a zoo without feeling the constriction of animals accustomed to roaming miles who find themselves confined to such small areas. Although I know that zoos do important research, save some animals from extinction, and that they also provide a close-up look for those unable to make the kind of trip we made, I can no longer be comfortable at them.

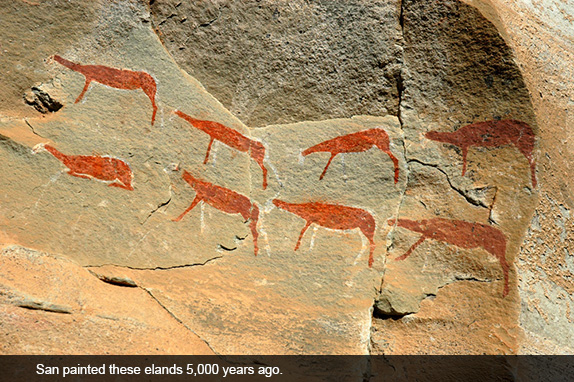

Hiking with a friend in the foothills of South Africa’s Drakensberg Mountains, our destinations were several San (Busman) rock art sites. Emerging from forest, we saw a herd of elands grazing in a field. Then we arrived at the rock art itself and viewed images of elands painted 5,000 years ago. The sense of continuity left us breathless.

But viewing large animals in the wild also holds another sort of poetry. We are in their world. Their rules apply. No longer is our environment so androcentric. It is as if we have parted a membrane of time and place. Inside looking in, we are able to see ourselves in a different light as well.

Responses to “Friday Voyage: Africa”